I have embarked on a wild goose chase, though to be clear it’s the chase that’s wild and not the goose. I left Amsterdam at dawn, drove the length of Holland before lunch, got turned about on Brussels’ notorious ring road, barreled through bucolic countryside and finally, at two o’clock, pulled into a vast parking lot in the midst of Flemish hay fields. High, high above, as if mocking all of us landlocked beings, glided a massive stork with a wingspan as wide as a minivan.

I had arrived at Pairi Daiza, a fifty-six-acre experiment that is part theme park, part nature preserve, part sweeping historical document. In 1056 the site witnessed the creation of Belgium’s first Catholic monastery, which thrived until 1780, when a family of nobles dismantled the church and built a castle from its bricks. In the 1990s a wealthy lawyer transformed the place into a bird park, but birds turned out to be just the beginning and today Pairi Daiza (Persian for “paradise”) is home to five thousand animals. It aims to imitate the world so that you can stroll from Asia to Africa to Europe and beyond, seeing the native flora and fauna of each as you go.

I am here for something uniquely Hawaiian: the nēnē, a goose endemic to Hawai‘i. There are twelve nēnē at Pairi Daiza, and the park’s curator, Koen Vanderscheuren, has offered to introduce me. Koen, bald and built like a bull, looks more like an aging boxer than Dr. Dolittle; he is responsible for all of the animals here, and he takes call after call as we talk, staving off various crises. In between, he tells me he grew up the son of a bird breeder and at 12 began training his own birds of prey; he still loves to hunt, using golden eagles, goshawks and peregrine falcons to go after pheasants and rabbits. His passion for birds drew him to Pairi Daiza on opening day twenty-two years ago, and within a year he’d been hired. The nēnē—four at the time—were at the park that day, too, and they quickly became Koen’s favorites. Whenever he entered the huge aviary where they lived, he sought them out.

Koen takes me to see the birds I’ve traveled all this way to meet. We walk through a crush of people—Pairi Daiza gets 1.75 million visitors a year—then enter the aviary. There are fewer birds than people, but not by many: I see eiders, herons, storks, swamphens, flamingos, egrets, spoonbills, ibises. Then, all of a sudden, there they are. Amid a delirium of color they are understated, even—if one is harsh—drab. But they are profoundly graceful and radiate a calm not seen in the other birds. They are, in a word, dignified. They watch me curiously as I approach. They are not frightened, not even wary. Self-possessed is what they are. I ask Koen why they were his favorites. He mentions their tranquility, their sociability, the way they come to you rather than you to them. Other birds approach for food, says Koen, but not the nēnē. “For me they are searching for direct contact,” he says. As if to prove everything Koen is saying, the nēnē surround us. They talk to us, making a sound too sweet-tempered to even approach a honk. “They support a lot of other animals around them,” says Koen. “They support everything.”

I’m struck by that and ask Koen if he’s ever heard of the aloha spirit.

“No,” he says. “What is that?”

“It’s said to be the national character of the Hawaiian people,” I explain. “They are famous for being very warm, very friendly. It’s said that their natural way of being is open and generous.”

The Flemish falconer nods. Looking around at the geese, he confirms, “It’s like the nēnē.”

Most of us who live in Hawai‘i know the nēnē. It is, after all, our state bird. We know how close it came to extinction a century ago, know it’s rallied a bit, know you now stand a good chance of spotting one if you’re in Haleakalā or Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park. We know that wild nēnē are classified as endangered and that it’s a crime to disturb them, so we try to stay away even though the gregarious creatures often head straight for us. Our nēnē are a symbol, a success story in a place that has seen much loss, an emblem of the possibility of environmental regeneration.

But virtually no one in Hawai‘i knows the story of the other nēnē, the ones beyond these Islands. Tell people in Hawai‘i that there are nēnē to be found in Dubai and Johannesburg and Guadalajara and you’ll astonish them. When I started to research this story, I knew only of Slimbridge, one of the most respected bird sanctuaries in the world, an oasis in the west of England that is the crown jewel of the country’s Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust. It was at Slimbridge that in the 1950s nēnē were bred so successfully by one of the twentieth century’s great ornithologists, Sir Peter Scott. I’d decided to go to Slimbridge to see the nēnē and had casually inquired whether I might find nēnē at other WWT wetlands. Not only could I, I learned, but by the end of my research I’d discovered that there were so many nēnē in the world that I could even buy a pair of my very own off the Internet for £185. And thus began my wild goose chase: I decided to zero in on northern Europe and meet as many nēnē as I could.

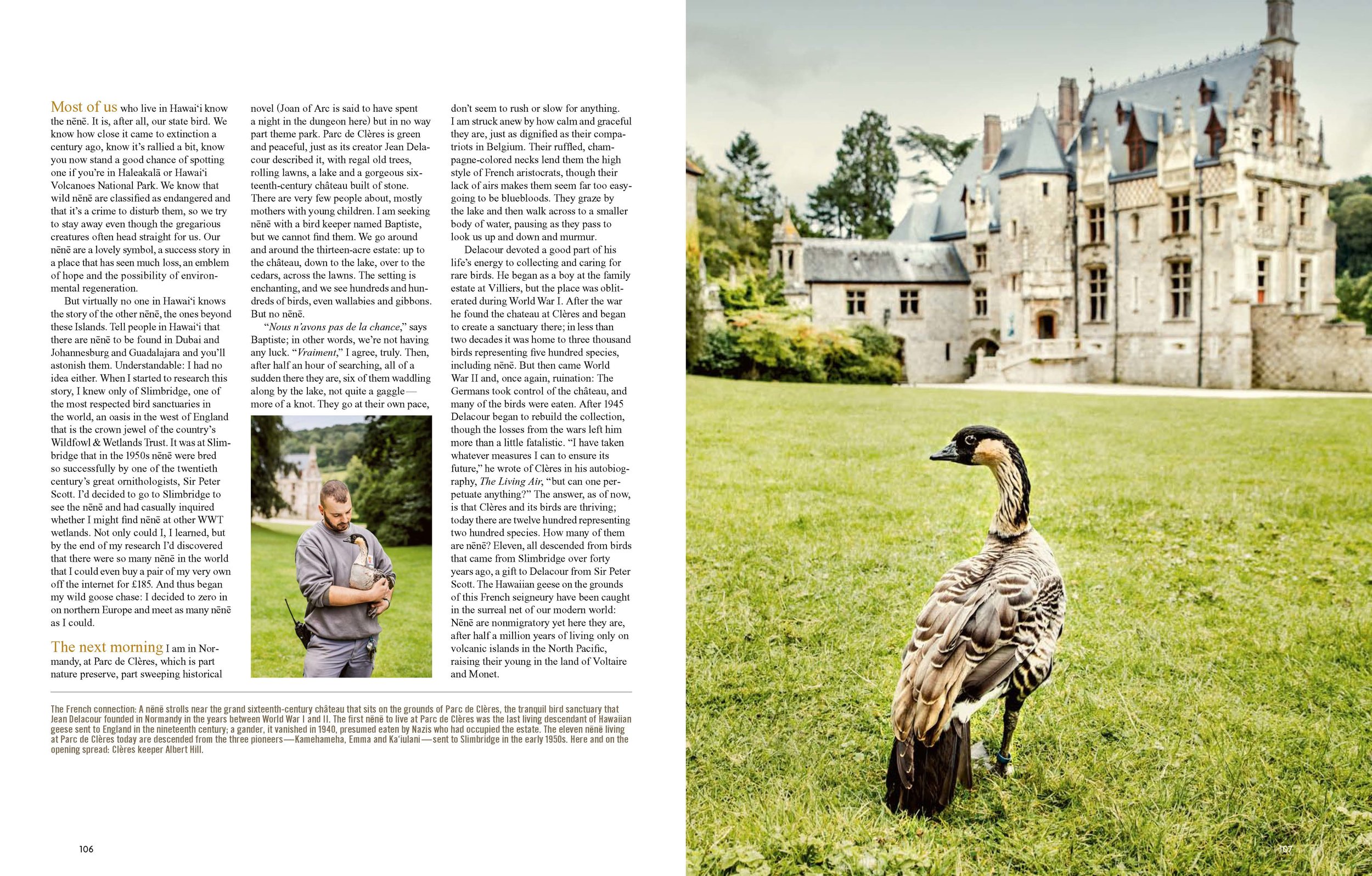

The next morning I am in Normandy, at Parc de Clères, which is part nature preserve, part sweeping historical document (Joan of Arc is said to have spent a night in the dungeon here) but in no way part theme park. Parc de Clères is green and peaceful, just as its creator Jean Delacour described it, with regal old trees, rolling lawns, a lake and a gorgeous sixteenth-century château built of stone. There are very few people about, mostly mothers with young children. I am seeking nēnē with a bird keeper named Baptiste, but we cannot find them. We go around and around the thirteen-acre estate: up to the château, down to the lake, over to the cedars, across the lawns. The setting is enchanting, and we see hundreds and hundreds of birds, even wallabies and gibbons. But no nēnē. “Nous n’avons pas de la chance,” says Baptiste; in other words, we’re not having any luck. “Vraiment,” I agree, truly. Then, after half an hour of searching, all of a sudden there they are, six of them waddling along by the lake, not quite a gaggle—more of a knot. They go at their own pace, don’t seem to rush or slow for anything. I am struck anew by how calm and graceful they are, just as dignified as their compatriots in Belgium. Their ruffled, champagne-colored necks lend them the high style of French aristocrats, though their lack of airs makes them seem far too easygoing to be bluebloods. They graze by the lake and then walk across to a smaller body of water, pausing as they pass to look us up and down and murmur.

Delacour devoted a good part of his life’s energy to collecting and caring for rare birds. He began as a boy at the family estate at Villiers, but the place was obliterated during World War I. After the war he found the chateau at Clères and began to create a sanctuary there; in less than two decades it was home to three thousand birds representing five hundred species, including nēnē. But then came World War II and, once again, ruination: The Germans took control of the château, and many of the birds were eaten. After 1945 Delacour began to rebuild the collection, though the losses from the wars left him more than a little fatalistic. “I have taken whatever measures I can to ensure its future,” he wrote of Clères in his autobiography, The Living Air, “but can one perpetuate anything?” The answer, as of now, is that Clères and its birds are thriving; today there are twelve hundred representing two hundred species. How many of them are nēnē? Eleven, all descended from birds that came from Slimbridge over forty years ago, a gift to Delacour from Sir Peter Scott. The Hawaiian geese on the grounds of this French seigneury have been caught in the surreal net of our modern world: Nēnē are nonmigratory yet here they are, after half a million years of living only on volcanic islands in the North Pacific, raising their young in the land of Voltaire and Monet.

After I leave the château, I walk a few hundred yards into the tiny town of Clères. It’s a time capsule: People wear shirts with wide lapels, drink cider at sidewalk cafés, puff up a storm, talk animatedly. There isn’t a cell phone or computer to be seen, which is endearing except that I need a Wi-Fi connection to map the four hundred miles back to Amsterdam. “Il n’y a pas de Wi-Fi ici, mademoiselle,” says everyone I ask, and by “ici” they mean the whole village. To get online I must drive ten miles—on the Rue Winston Churchill: Merci pour la guerre!—to the next village. But how will I actually find Wi-Fi once I’m there? No need to worry. Driving through narrow streets flanked by centuries-old buildings, I see a picture of a hula girl and a large sign that reads “Hawaii Pizza.” I pull over. Inside the shop are two delightful Algerian pizzaiolos, Mohamed Ali Benmeriem and Maâmar. “Je suis d’Hawai‘i!” I say. Mohamed beams and tells me he honeymooned in Waikïkï. They welcome me to use their Wi-Fi and give me the password: “aloha.” And thanks to the map I reach Amsterdam before midnight.

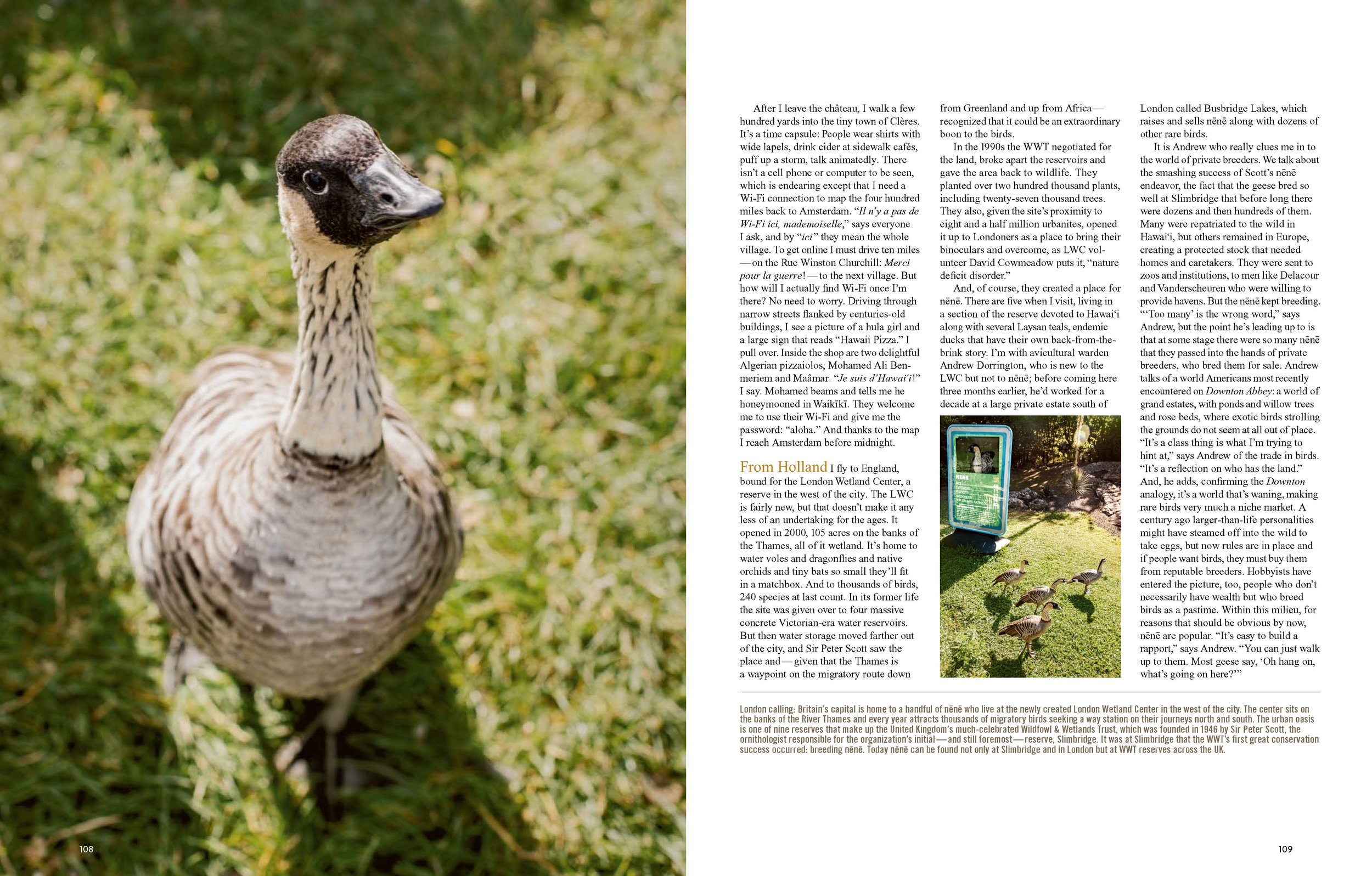

From Holland I fly to England, bound for the London Wetland Center, a reserve in the west of the city. The LWC is fairly new, but that doesn’t make it any less of an undertaking for the ages. It opened in 2000, 105 acres on the banks of the Thames, all of it wetland. It’s home to water voles and dragonflies and native orchids and tiny bats so small they’ll fit in a matchbox. And to thousands of birds, 240 species at last count. In its former life the site was given over to four massive concrete Victorian-era water reservoirs. But then water storage moved farther out of the city, and Sir Peter Scott saw the place and—given that the Thames is a waypoint on the migratory route down from Greenland and up from Africa—recognized that it could be an extraordinary boon to the birds. In the 1990s the WWT negotiated for the land, broke apart the reservoirs and gave the area back to wildlife. They planted over two hundred thousand plants, including twenty-seven thousand trees. They also, given the site’s proximity to eight and a half million urbanites, opened it up to Londoners as a place to bring their binoculars and overcome, as LWC volunteer David Cowmeadow puts it, “nature deficit disorder.”

And, of course, they created a place for nēnē. There are five when I visit, living in a section of the reserve devoted to Hawai‘i along with several Laysan teals, endemic ducks that have their own back-from-the-brink story. I’m with avicultural warden Andrew Dorrington, who is new to the LWC but not to nēnē; before coming here three months earlier, he’d worked for a decade at a large private estate south of London called Busbridge Lakes, which raises and sells nēnē along with dozens of other rare birds.

It is Andrew who really clues me in to the world of private breeders. We talk about the smashing success of Scott’s nēnē endeavor, the fact that the geese bred so well at Slimbridge that before long there were dozens and then hundreds of them. Many were repatriated to the wild in Hawai‘i, but others remained in Europe, creating a protected stock that needed homes and caretakers. They were sent to zoos and institutions, to men like Delacour and Vanderscheuren who were willing to provide havens. But the nēnē kept breeding. “‘Too many’ is the wrong word,” says Andrew, but the point he’s leading up to is that at some stage there were so many nēnē that they passed into the hands of private breeders, who bred them for sale. Andrew talks of a world Americans most recently encountered on Downton Abbey: a world of grand estates, with ponds and willow trees and rose beds, where exotic birds strolling the grounds do not seem at all out of place. “It’s a class thing is what I’m trying to hint at,” says Andrew of the trade in birds. “It’s a reflection on who has the land.” And, he adds, confirming the Downton analogy, it’s a world that’s waning, making rare birds very much a niche market. A century ago larger-than-life personalities might have steamed off into the wild to take eggs, but now rules are in place and if people want birds, they must buy them from reputable breeders. Hobbyists have entered the picture, too, people who don’t necessarily have wealth but who breed birds as a pastime. Within this milieu, for reasons that should be obvious by now, nēnē are popular. “It’s easy to build a rapport,” says Andrew. “You can just walk up to them. Most geese say, ‘Oh hang on, what’s going on here?’”

As Andrew and I talk, the London nēnē watch us from about five feet away. There are two pairs and a female, and one of the males has his neck out and his head down. That, Andrew tells me, is defensive behavior—a fact that only underscores his point about their temperament. Other geese would likely rise up and let it rip if they were feeling defensive: hiss, flap their wings, rush you. The nēnē: Meh.

After I leave the LWC, I walk along the Thames to the B&B where I’m staying. It’s run by Wendy Newnham, a longtime volunteer at the LWC as well as a “world lister,” which basically puts her at the very top of a global bird-watching hierarchy and means that she travels the globe sighting and recording different species, many of which are in trouble in today’s world, threatened by climate change, pollution and habitat loss. Wendy, too, is enamored of nēnē. Earlier, over a very British breakfast complete with homemade marmalade, she’d recalled seeing them for the first time. “They were absolutely beautiful. I remember thinking, ‘Thank goodness they aren’t extinct!’” Every year, to help LWC veterinarians doing annual avian health checks, she holds the nēnē in her arms as the vets draw blood. Newnham had almost swooned recalling the feel of their necks against her skin: “Like velvet.”

As exceptional as all three places I’ve visited are, the most distinctive is yet to come. It is down south, in East Sussex. I lived in England for a year as a child, and on the weekends my family was forever heading off to see kooky British attractions like tiny houses built for fairies and the museum of cheddar cheese. So the Bentley Wildfowl and Motor Museum—chicks and cars, innit?—doesn’t feel like that much of a stretch even when I find out that it is also home to a miniature railroad and (naturally) a tea shop. What does make it extravagantly quirky is the woman presiding over it all, Ingrid Christophersen. When Ingrid picks me up in her motorcar to take me to Bentley, it feels a bit like Mr. Toad is at the wheel. Not because there is anything even remotely Toad-like about Ingrid—a onetime skier on the British national team, she is still trim and beautiful in her 70s—but it is her wild enthusiasm as she speeds through the narrow country lanes that calls to mind the auto-besotted amphibian. As she bombs along, Ingrid tells the tale of Bentley. It belonged to Uncle Gerald, she explains, he being Gerald Askew of the Rank family, which made masses of money in flour. Gerald bought the historic estate of Bentley in 1939. Later he visited Slimbridge, became friends with Sir Peter Scott and was so inspired that he decided to create a bird sanctuary of his own. Scott started off the whole endeavor by making Uncle Gerald the gift of a pair of nēnē.

When we arrive at Bentley, Ingrid turns me over to Chris Keep, the bird keeper. Chris is large and laconic, and had Monty Python ever done a bird film (Beautiful Plumage?), he would have fit right in. Though he calls Ingrid “mad as a box of frogs,” he clearly has a huge affection for her and she for him (“The absolute expert,” she says of him. “He’s in charge of everything, really”). Chris has been at Bentley since 1981. He trained as a teacher but decided he didn’t really like children and that birds were the way to go. “I escaped to Bentley,” he says as he leads me down to see the wildfowl. He also warns me that the nēnē might be a little skittish—there is a wild mink about, a creature that can and will kill nēnē.

The dream of Uncle Gerald, which Chris has brought to ever-greater fruition over the years, is apparent as we walk: In the lower part of the estate, we pass through a gate and enter a landscaped world of pathways and ponds. For the fourth time in nearly as many days, I am in a place where birds of all kinds are predominant. We see red-crested pochards, Cuban whistling ducks, Pacific white-fronted geese, New Zealand brown teals. We see what for me are the strangest birds of the trip, a pair of Egyptian geese that have red-orange eyes and warn us off with a noise that sounds like a machine gun.

As we near a particularly large pond, we spot nēnē on the other side of it. “They want to be where they can watch what’s happening,” says Chris. The mink definitely has them spooked: These nēnē are on guard. And that’s interesting because one of the things you always hear about nēnē—given that they evolved in isolation—is that they are fearless and thus easy to pick off. But what I’m seeing proves (to me at least) that these geese are not without a common-sense instinct for survival. Still, that might not be enough. “I’ve had a fox in two or three times,” says Chris, “and it’s always the nēnē that get wiped out first.”

I ask Chris how many nēnē he thinks are in the UK now. “I couldn’t hazard a guess,” he says. “Nēnē were the thing to have in the old days; they had quite a prestige then. Now everybody’s getting nēnē. They’re one of the easiest things to breed.” Bentley doesn’t sell any of its birds, but it does trade them with zoos and other institutions.

En route back to meet Ingrid, we stop in the motor museum. It’s surprisingly large and full of dozens of super-cool cars, including Britain’s first electric car, an Enfield from 1971. Nearby there’s an enclosure with many small brown ducks. I am astonished when Chris tells me that some are koloa, another bird endemic to Hawai‘i, another near-extinction story. I’ve never seen a koloa in Hawai‘i, yet here they are in East Sussex, right in front of me.

Over lunch at the tea shop, Ingrid tells story after story: About seeing nēnē at Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park in the 1970s, when her father was a visiting professor at the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo. About being made a Member of the British Empire by Prince Charles for her services to skiing. About being secretary to Thor Heyerdahl, he of Kon Tiki fame. “Thor Heyerdahl?” I ask in amazement. “Not ‘Thor,’ darling,” she reprimands. “Toor.” Of Bentley she says, “It has been to the wars.” After Gerald died it passed to his widow, Mary, but death taxes nearly wiped Mary out, so in 1978 she gave the hundred-acre wildfowl portion of the estate to the county for free. After twenty-five years the county decided it didn’t want the land and asked her to take it back—and to pay them £1.25 million to boot. Mary managed but it was tough. When she died she left a life tenancy at Bentley to her cousin Ingrid, who now lives here in a house that dates to the Tudors.

In the Wong Audiovisual Center in Sinclair Library on the UH Mänoa campus, there is a short and obscure film called Guided by the Nene. Within it lies the origin of this story. Grainy footage shot decades ago shows a man in Hilo named Herbert Shipman talking about the nēnē. “My mother had one when I was quite young,” he says. “It used to accompany her to Hilo when she rode in on horseback. It flew ahead, and then it waited by the horse when she was in some of the stores. That was before 1900. Somebody shot it one day.” By the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, things had gone from bad to worse for nēnē in Hawai‘i: The rats, dogs and pigs the Polynesians brought had been joined by guns, cattle and mongooses, and all spelled trouble for the geese. In 1878 there were still perhaps twenty-five thousand nēnē; by the 1930s there were believed to be only thirty or forty left in the wild.

Herbert had been given a pair when he was a teenager, around 1914, and then, soon after, another pair. He began breeding them. He maintained a small flock—a fact that came to the attention of Sir Peter Scott. As Sir Peter remembers, “I was keen on geese, and I’d heard that this goose was getting rare. Well, I wrote to Mr. Herbert Shipman back in 1938, and he wrote to confirm that he had a small collection of these geese living in his garden close by the sea at Hilo. I asked if he’d consider sending a pair to me in England, and he replied that he would if I’d come out and fetch them.”

Sir Peter was the only child of explorer Robert Falcon Scott, who’d died during his quest to become the first man to reach the South Pole. Trapped without food in frigid weather and facing death, Scott had written his wife, Kathleen, of their two-year-old son, “Make the boy interested in natural history if you can.” Kathleen did just that. By 1938, the year he wrote Shipman, the younger Scott was 29 and turning toward a life that would ultimately lead him to found not just the WWT, but also the World Wildlife Fund. He was an Olympic sailor, a champion glider, an acclaimed painter and a decorated naval officer, but more than anything he was what his father hoped he would be: a person dedicated to the natural world.

Scott’s plans for the nēnē were temporarily derailed by World War II, but once the fighting was over he sent John Yelland to Hilo to advise on a fledgling nēnē conservation project in Pōhakuloa and to collect a pair of nēnē from Shipman. These were not the first nēnē to travel to England—those had been sent in the 1830s when now-famed botanist David Douglas (for whom the Douglas fir is named) shipped a pair that wound up with the Zoological Society of London. In fact, the nēnē’s scientific name, Branta sandvicensis, traces even earlier in English history, to the Earl of Sandwich and Hawai‘i’s colonial moniker, the Sandwich Islands.

When the Hilo geese arrived at Slimbridge, they both built nests: Yelland had returned with two females. “A wire to Mr. Shipman,” recalled Scott, “promptly brought a gander.” It was a comic hitch in a plan that otherwise worked brilliantly. The birds were named for Hawaiian royalty (the females Emma and Ka‘iulani, the male Kamehameha), and to call them effective breeders would be an understatement. All of the nēnē I’ve seen on this trip descend from Emma, Ka‘iulani and Kamehameha. Many of the nēnē in Hawai‘i do, too: Two hundred of their descendants have been released into the wild in the Islands.

Slimbridge is the last stop on my tour. To reach it I meet the WWT’s Chris Cavalier at the Notting Hill Gate tube station in London at 7 a.m., and we speed west across England. Slimbridge is in the country, near Bristol; it sits on land that Sir Peter leased in 1946. “Your wetland adventure starts here,” reads a sign at the entrance; in the lobby is a giant painting by Sir Peter of nēnē flying near Mauna Kea. Here I meet Tina Bouttle, the animal registrar, who has cared for nēnē at Slimbridge for thirteen years. Tina reveres Scott, and her affection for the nēnē is apparent in everything she says about them: how cheeky they are (“If there’s a gate, they’ll sneak through it”), how they have the broadest diet of any goose (“You’ll have nēnē with purple rings around their faces from blackberries”). When her daughters were babies, Tina slung them over her back as she cared for the geese. For years she worked with the adopt-a-nēnē program, wherein Brits sponsor one of the WWT nēnē. “We had one couple,” she says. “They called their nēnē Pearl and came in every week like clockwork to see her. I mean, they absolutely loved her. When eventually Pearl did pass away, I had to ring them up, and they were in tears.”

Tina takes me to meet the front-of-the-house nēnē and encourages me to feed one. This practice is actively encouraged at Slimbridge, particularly when it comes to young children: The idea is to give the kids a sense of connection and wonder that will fuel a vibrant and protective relationship with nature. The nēnē are perfect for this, says Tina, because they are so gentle. But given that feeding them is forbidden in Hawai‘i, it still feels somehow wrong even though these are not wild birds. I proffer my hand casually, figuring the nēnē will decide whether it wants the food. It does. It takes it from my hand with such care that it never once touches my skin. When we pass a group of greylag geese, Tina suggests I try feeding them for comparison. I do. They fight each other to get to me, and the biggest bruiser seizes the food, his beak stabbing into my palm like a jackhammer.

On one of the pathways Tina shows me a huge nēnē crafted from over ten thousand pieces of Lego; it’s four times the size of an actual nēnē. As playful and charming as it is, it is also poignant. When human beings arrived in Hawai‘i, there were in fact at least three endemic species of geese living in the Islands: the nēnē, the nēnē nui and the giant Hawaiian goose. The nēnē nui and the giant Hawaiian goose, which was four times the size of the nēnē, are now extinct, gone for hundreds of years; when their numbers dwindled, there were no Shipmans and Scotts to save them.

Tina takes me to the duckery to meet Phoebe Vaughan, the duckery warden, who carries on the work begun here over half a century ago: She breeds nēnē and many other rare and endangered birds; she estimates she and her colleagues have bred over five thousand birds in the nine years she’s been here, because Slimbridge’s commitment to saving all of the world’s birds is as strong as ever.

Phoebe’s affection for the nēnē runs deep as does her knowledge about them, but she’s not sentimental—just the opposite. “I’m not interested in taming birds,” Phoebe says. “We don’t want birds that don’t know what they are. Nēnē are very susceptible to that because of their intelligence. You can tame a nēnē very quickly, and it’s not always good for them.” Phoebe tracks every step of a Slimbridge nēnē’s life: makes sure its genetics are as favorable as they can be before it’s born, keeps an eye on the parenting it receives, plays matchmaker to pair it with a genetically appropriate mate, monitors its egg-laying and nesting and gosling-rearing stages, watches for infirmities when it’s old. She stays as hands-off as possible, and if she does get involved, it’s in the interest of the species: If it’s bitterly cold she might replace a nesting female’s eggs with wooden decoys and pop the real ones in an incubator. When the eggs are ready to hatch, she might place them with particularly capable parents; there is a wide range in nēnē parenting skills. She takes me to see a pair of eight-year-old parents she calls “just brilliant.” What makes them so good? “Their behavior, their connection to one another, their knowledge of where to find food and water, their knowledge of where to let their juveniles enter water,” she says. “We sometimes lose young nēnē because their parents will lead them down a vertical bank and they can’t get out again. This pair knows to take its young down round the edges to enter by the beaches.”

I ask a question I’ve been wondering about as I’ve traveled across northern Europe: How do the nēnē handle the cold? Easily, Phoebe says Some half a million years ago the nēnē evolved from Canada geese that had migrated to the Islands, and they’ve inherited a certain level of hardiness from those genes. Overall, Phoebe says, the nēnē are “chilled. A bit ridiculously chilled in a way. They just wander around going, ‘Oh, I’ll do that. Oh, I’ll do that,’ as the fancy takes them.”

Phoebe takes me through the duckery. At one point a group of five female nēnē runs toward us. They are young and vital and gorgeous. “My little gang of ladies,” says Phoebe. All are five months old, and they’re from three different families. They come up to us for the same reason the geese at Pairi Daiza had approached me a few days before. “They’re interested in what we’re doing,” says Phoebe. “They have no interest in being touched or being hand-fed or anything. They’re simply curious.”

As I prepare to leave the duckery, Phoebe and Tina offer to show me something very precious to Slimbridge, something rarely seen. It is one of the original three nēnē, Ka‘iulani, who in 1960 was stuffed and mounted after she died. They have brought her out of storage for me, and fifty-six years on she remains faultlessly preserved and beautiful. Seeing her is the perfect end to this journey. I think of her beginnings in Shipman’s garden, her trip to England, her double lives in Hawai‘i and the UK. I think, too, of the princess for whom she’s named, Victoria Ka‘iulani, who had a Hawaiian mother and a Scottish father and who also lived a life split between Hawai‘i and the UK. That Ka‘iulani carried the hopes of a nation that wished to see her ascend to the throne of a restored Hawaiian Kingdom, but it was not to be: She died in 1899 at just 23. But the Ka‘iulani before me? She was blessed with a different destiny. She helped to save her species.