In 1971 a teenager named Mark Blackburn boarded a Pan Am flight in Los Angeles bound for Tahiti. He was young but already a rock star of the coin-collecting world, a savvy kid who’d bought and sold his way out of his family’s meager fortunes and into renown. At 18 he dished out a chunk of his hard-won cash for a round-the-world ticket and headed for the airport. First stop: Tahiti.

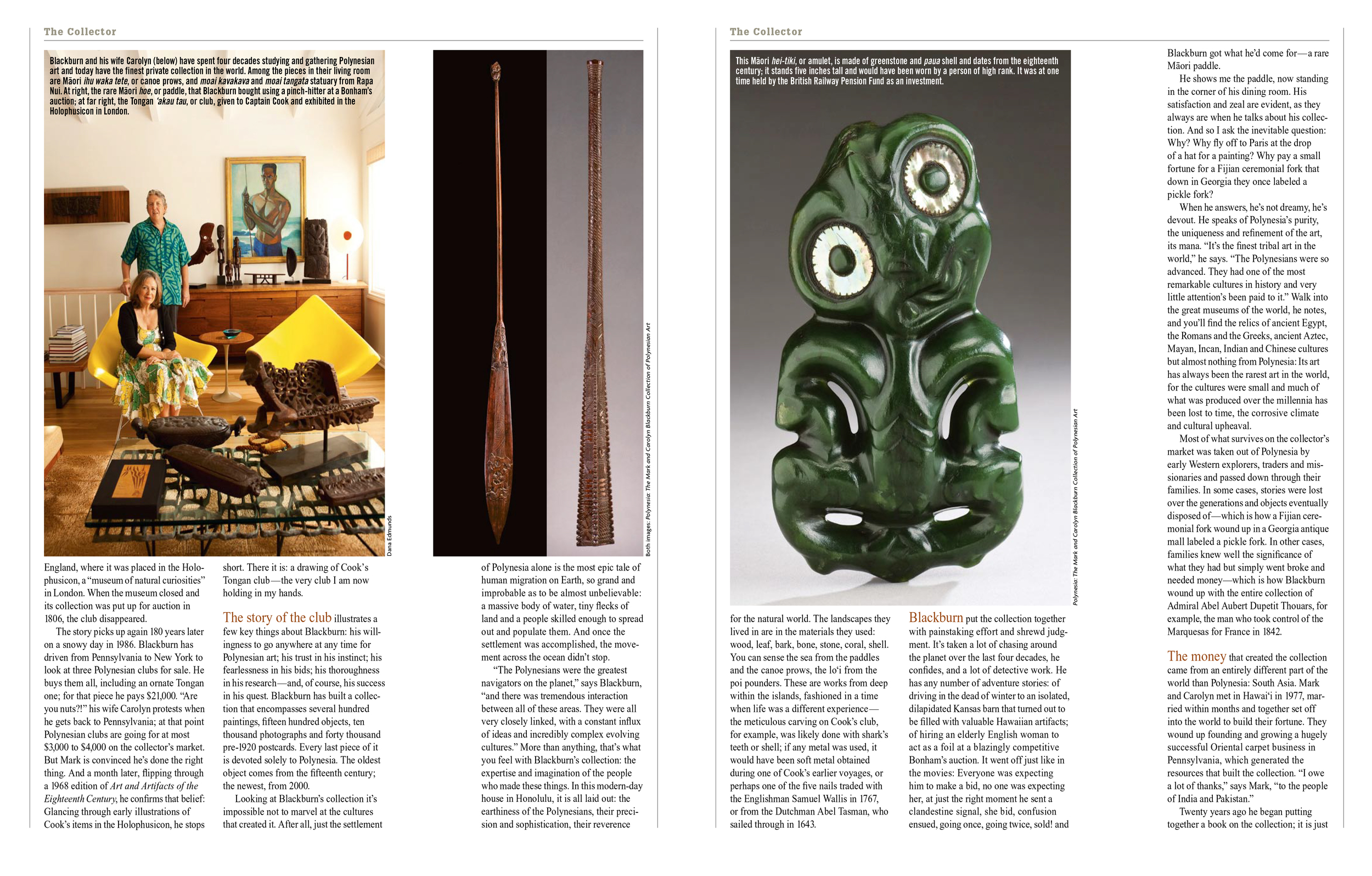

Blackburn was a man under the influence from the moment he arrived. The purity of the landscape, the potency of the people, the intricacy of the culture: He loved it all. Next came New Zealand, and in the museums, looking at the graceful and elaborate lines in Mäori art, Blackburn was captivated further. He continued on his journey, carrying memories of the islands with him, and when, not long after, he was in a flea market in Germany and he saw a Mäori hei-tiki carving, he bought it—the first acquisition in what has become the finest private collection of Polynesian art in the world.

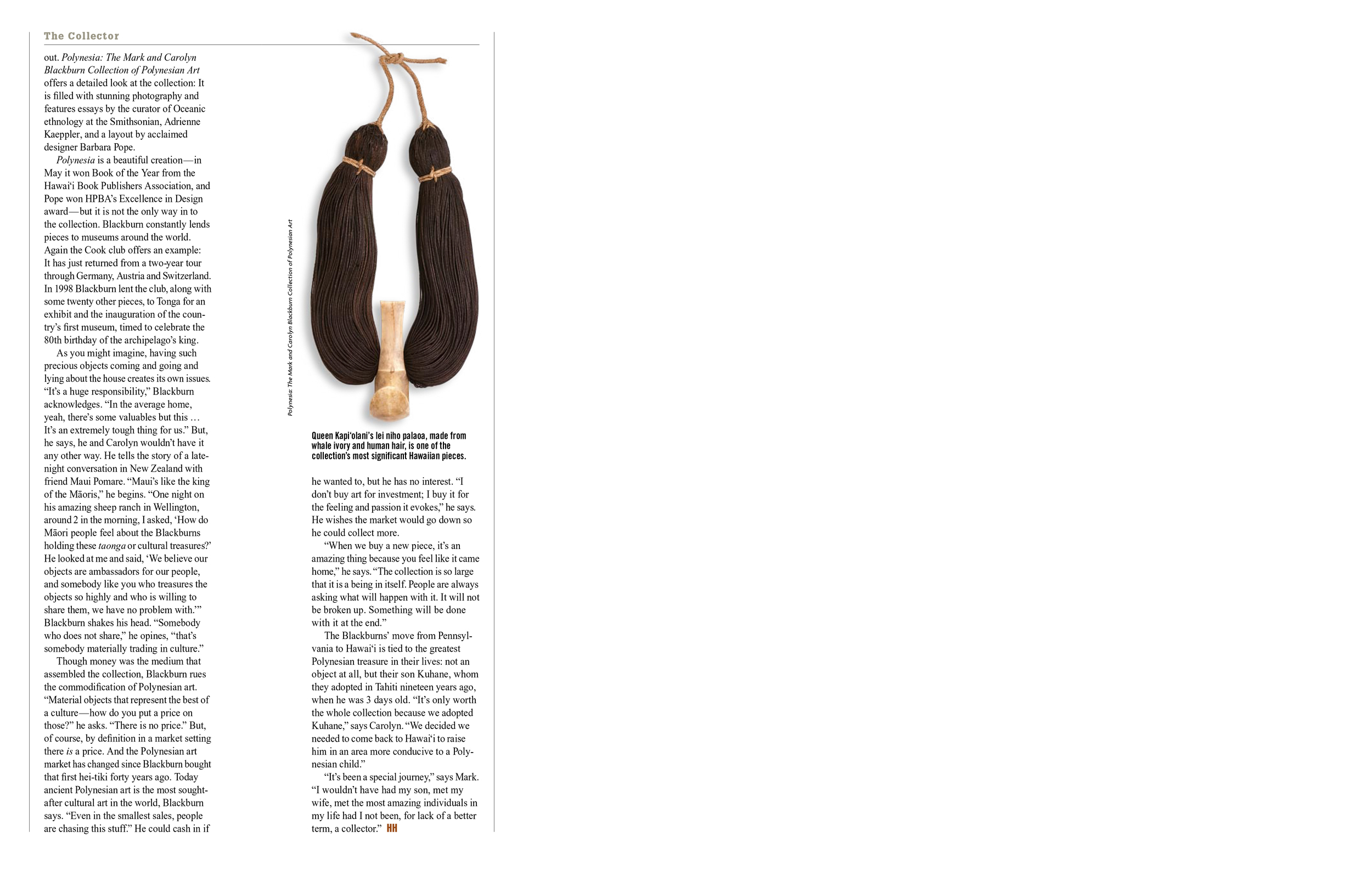

It’s all in his house in Honolulu, which is utterly startling. You walk in and there’s Queen Ka‘ahumanu’s kapa on the wall, a wooden turtle owned by Fiji’s great chief Cakobau next to the sofa, a stone ti‘i from a Tahitian marae over by the sideboard. Maori feather boxes cover the coffee table. There’s the cup Bligh used to measure rations after the mutiny on the Bounty, Paul Gauguin’s poi pounder on Hiva O‘a: Every nook of the house has something extraordinary. Blackburn pulls open a drawer and looks in. “This is Kapi‘olani’s necklace,” he says, and beside it, “Lili‘uokalani’s feather lei.” The next drawer has necklaces from the Marquesas made of porpoise teeth; the next, Mäori hand clubs. Austral Island paddles—triumphs of line and form that would be right at home in the MoMA—are suspended on an adjoining wall. Even the bathroom has a mindblower: Hanging over the toilet is an Oct. 27, 1906 edition of the Fiji Times newspaper printed on kapa.

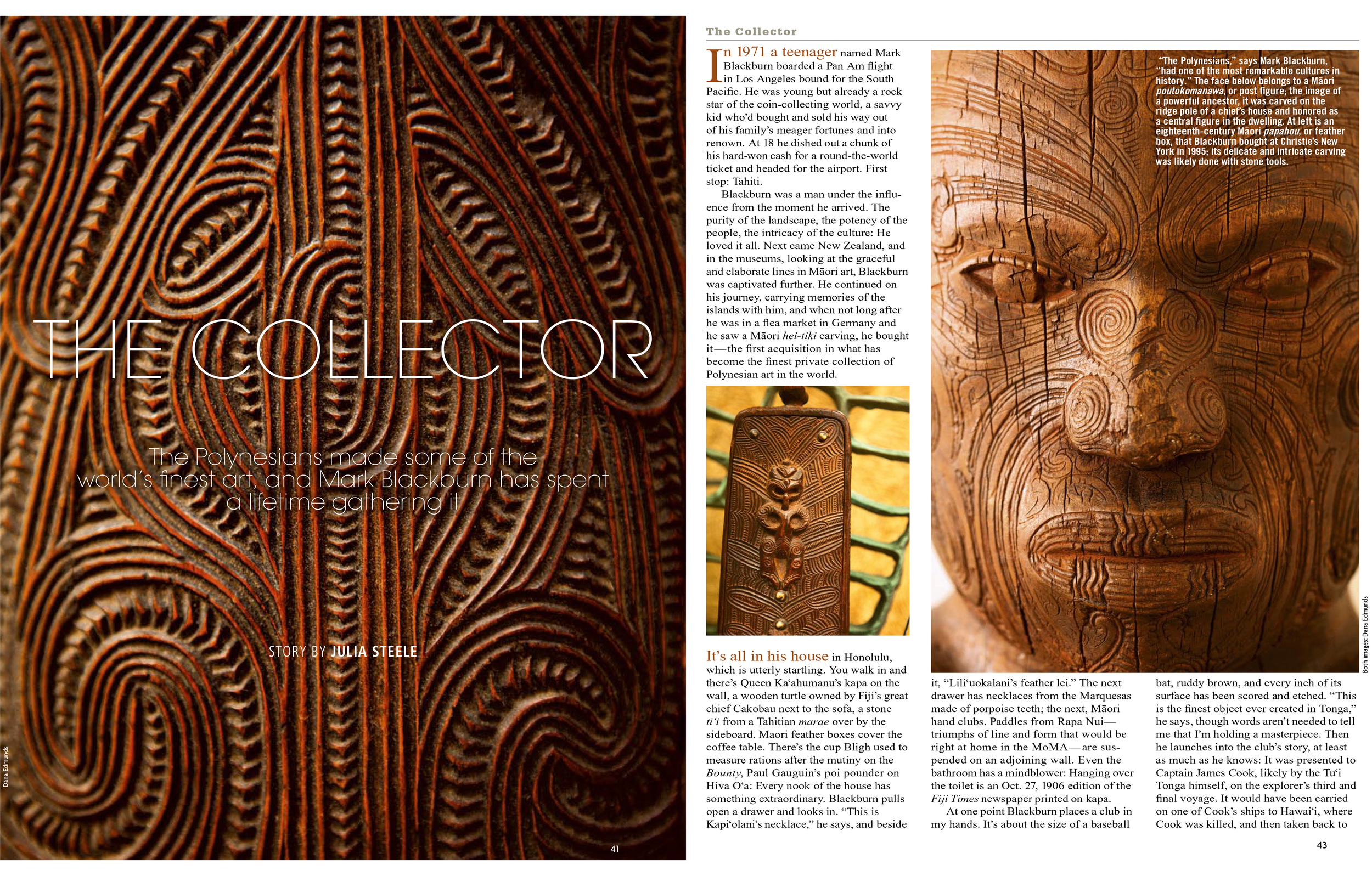

At one point Blackburn places a club in my hands. It’s about the size of a baseball bat, ruddy brown, and every inch of its surface has been scored and etched. “This is the finest object ever created in Tonga,” he says, though words aren’t needed to tell me that I’m holding a masterpiece. Then he launches into the club’s story, at least as much as he knows: It was presented to Captain James Cook, likely by the Tu‘i Tonga himself, on the explorer’s third and final voyage. It would have been carried on one of Cook’s ships to Hawai‘i, where Cook was killed, and then taken back to England, where it was placed in the Holophusicon, a “museum of natural curiosities” in London. When the museum’s collection was put up for auction in 1806, the club disappeared.

The story picks up again 180 years later on a snowy day in 1986. Blackburn has driven from Pennsylvania to New York to look at three Polynesian clubs for sale. He buys them all, including an ornate Tongan one; for that piece he pays $21,000. “Are you nuts?!” his wife Carolyn protests when he gets back to Pennsylvania; at that point Polynesian clubs are going for at most $3,000 to $4,000 on the collector’s market. But Mark is convinced he’s done the right thing. And a month later, flipping through a 1968 edition of Art and Artifacts of the Eighteenth Century, he confirms that belief: Glancing through early illustrations of Cook’s items in the Holophusicon, he stops short. There it is: a drawing of Cook’s Tongan club—the very club I am now holding.

The story of the club illustrates a few key things about Blackburn: his willingness to go anywhere at any time for Polynesian art; his trust in his instinct; his fearlessness in his bids; his thoroughness in his research—and, of course, his success in his quest. Blackburn has built a collection that encompasses several hundred paintings, fifteen hundred objects, ten thousand photographs and forty thousand pre-1920 postcards. Every last piece of it is devoted solely to Polynesia. The oldest object comes from the fifteenth century; the newest, from 2000.

Looking at Blackburn’s collection it’s impossible not to marvel at the cultures that created it. After all, just the settlement of Polynesia is the most epic tale of human migration on Earth, so grand and improbable as to be almost unbelievable: a massive body of water, tiny flecks of land and a people skilled enough to spread out and populate them. And once the settlement was accomplished, the movement across the ocean didn’t stop.

“The Polynesians were the greatest navigators on the planet,” says Blackburn, “and there was tremendous interaction between all of these areas. They were all very closely linked, with a constant influx of ideas and incredibly complex evolving cultures.” More than anything, that’s what you feel with Blackburn’s collection: the expertise and imagination of the people who made these things. In this modern-day house in Honolulu, it is all laid out: the earthiness of the Polynesians, their precision and sophistication, their reverence for the natural world. The landscapes they lived in are in the materials they used: wood, leaf, bark, bone, stone, coral, shell. You can sense the sea from the paddles and the canoe prows, the lo‘i from the poi pounders. These are works from deep within the islands, fashioned in a time when life was a different experience—the meticulous carving on Cook’s club, for example, was likely done with shark’s teeth or shell; if any metal was used, it would have been soft metal obtained during one of Cook’s earlier voyages, or perhaps one of the five nails traded with the Englishman Samuel Wallis in 1767, or from the Dutchman Abel Tasman, who sailed through in 1643.

Blackburn put the collection together with painstaking effort and shrewd judgment. It’s taken a lot of chasing around the planet over the last four decades, he confides, and a lot of detective work. He has any number of adventure stories: of driving in the dead of winter to an isolated, dilapidated Kansas barn that turned out to be filled with valuable Hawaiian artifacts; of hiring an elderly English woman to act as a foil at a blazingly competitive Bonham’s auction. It went off just like in the movies: Everyone was expecting him to make a bid, no one was expecting her, at just the right moment he sent a clandestine signal, she bid, confusion ensued, going once, going twice, sold! and Blackburn got what he’d come for, a rare Mäori paddle.

He shows me the paddle, now standing in the corner of his dining room. His satisfaction and zeal are evident, as they always are when he talks about his collection. And so I ask the inevitable question: Why? Why fly off to Paris at the drop of a hat for a painting? Why pay a small fortune for a Fijian ceremonial fork that down in Georgia they once labeled a pickle fork?

When he answers, he’s not dreamy, he’s devout. He speaks of Polynesia’s purity, the uniqueness and refinement of the art, its mana. “It’s the finest tribal art in the world,” he says. “The Polynesians were so advanced. They had one of the most remarkable cultures in history and very little attention’s been paid to it.” Walk into the great museums of the world, he notes, and you’ll find the relics of ancient Egypt, the Romans and the Greeks, ancient Aztec, Mayan, Incan, Indian and Chinese cultures but almost nothing from Polynesia: Its art has always been the rarest art in the world, for the cultures were small and much of what was produced over the millennia has been lost to time, the corrosive climate and cultural upheaval.

Most of what survives on the collector’s market was taken out of Polynesia by early Western explorers, traders and missionaries and passed down through their families. In some cases, stories were lost over the generations and objects eventually disposed of—which is how a Fijian ceremonial fork wound up in a Georgia antique mall labeled a pickle fork. In other cases, families knew well the significance of what they had but simply went broke and needed money—which is how Blackburn wound up with the entire collection of Admiral Abel Aubert Dupetit Thouars, for example, the man who took control of the Marquesas for France in 1842.

The money that created the collection came from an entirely different part of the world than Polynesia: South Asia. Mark and Carolyn met in Hawai‘i in 1977, married within months and together set off into the world to build their fortune. They wound up founding and growing a hugely successful Oriental carpet business in Pennsylvania, which generated the resources that built the collection. “I owe a lot of thanks,” says Mark, “to the people of India and Pakistan.”

Twenty years ago he began putting together a book on the collection; it is just out. Polynesia: The Mark and Carolyn Blackburn Collection of Polynesian Art offers a detailed look at the collection: It is filled with stunning photography and features essays by the curator of Oceanic ethnology at the Smithsonian, Adrienne Kaeppler, and a layout by acclaimed designer Barbara Pope.

Polynesia is a beautiful creation—in May it won Book of the Year from the Hawai‘i Book Publishers Association, and Pope won HPBA’s Excellence in Design award—but it is not the only way in to the collection. Blackburn constantly lends pieces to museums around the world. Again the Cook club offers an example: It has just returned from a two-year tour through Germany, Austria and Switzerland. In 1998 Blackburn lent the club, along with some twenty other pieces, to Tonga for an exhibit and the inauguration of the country’s first museum, timed to celebrate the 80th birthday of the archipelago’s king.

As you might imagine, having such precious objects coming and going and lying about the house creates its own issues. “It’s a huge responsibility,” Blackburn acknowledges. “In the average home, yeah, there’s some valuables but this … It’s an extremely tough thing for us.” But, he says, he and Carolyn wouldn’t have it any other way. He tells the story of a late-night conversation in New Zealand with friend Maui Pomare. “Maui’s like the king of the Mäoris,” he begins. “One night on his amazing sheep ranch in Wellington, around 2 in the morning, I asked, ‘How do Mäori people feel about the Blackburns holding these taonga or cultural treasures?’ He looked at me and said, ‘We believe our objects are ambassadors for our people, and somebody like you who treasures the objects so highly and who is willing to share them, we have no problem with.’” Blackburn shakes his head. “Somebody who does not share,” he opines, “that’s somebody materially trading in culture.”

Though money was the medium that assembled the collection, Blackburn rues the commodification of Polynesian art. “Material objects that represent the best of a culture—how do you put a price on those?” he asks. “There is no price.” But, of course, by definition in a market setting there is a price. And the Polynesian art market has changed since Blackburn bought that first hei-tiki forty years ago. Today ancient Polynesian art is the most sought after cultural art in the world, Blackburn says. “Even in the smallest sales, people are chasing this stuff.” He could cash in if he wanted to, but he has no interest. “I don’t buy art for investment; I buy it for the feeling and passion it evokes,” he says. He wishes the market would go down so he could collect more.

“When we buy a new piece, it’s an amazing thing because you feel like it came home,” he says. “The collection is so large that it is a being in itself. People are always asking what will happen with it. We think about it all the time. It will not be broken up. Something will be done with it at the end.”

The Blackburns’ move from Pennsylvania to Hawai‘i is tied to the greatest Polynesian treasure in their lives: not an object at all, but their son Kuhani, whom they adopted in Tahiti nineteen years ago, when he was 3 days old. “It’s only worth the whole collection because we adopted Kuhani,” says Carolyn. “We decided we needed to come back to Hawai‘i to raise him in an area more conducive to a Polynesian child.”

“It’s been a special journey,” says Mark. “I wouldn’t have had my son, met my wife, met the most amazing individuals in my life had I not been, for lack of a better term, a collector.”