No one really knew what to do. All of the women agreed that they’d rather be dragged off the property than leave voluntarily. They met frequently, over coffee and doughnuts from the corner ABC store, to discuss the eviction, their options and their fate. Finally, on June 2, two days before they were due to be evicted, they decided that as a statement of protest against the eviction and the destruction of affordable rentals for luxury condominiums, they would barricade themselves into one of the empty buildings on the lot after midnight on June 4 and stay there until they were arrested. No one thought that would take very long.

Early in 1990, a Japanese corporation called U.S.A. Pensee began buying properties clustered in a block of Waikiki bound by Kapili Street and Liliuokalani Avenue and bisected by Tusitala Street. The area, the former home of Hawaiian royalty (see “Home Paradise Lost” sidebar), contained a number of old, single-story wooden cottages and a few low-rise apartment buildings. About 75 people lived on Tusitala Street (as the block was known) and it was a popular place: rents were low, neighbors were friendly and jobs, the bus and the beach were all nearby. Despite its location in the core of Waikiki, it was a fairly quiet area.

U.S.A. Pensee spent approximately $31 million buying up property in the block. Once Pensee had acquired the area, The Property Managers, Ltd., a local property management firm headed by P.J. Moore stepped in to do just that. Moore sent notification to the tenants that the Property Managers was now handling the properties and she and Tom Patas, a Property Managers representative, visited the neighborhood to inspect the properties and talk with the residents.

Area residents who were approached by the company say they were assured they would be able to stay in their homes for at least two or three more years. They say they were told that Pensee had no plans to develop the land at that point (The Property Managers denies this and refused to discuss this story with the Honolulu Weekly since the matter is currently in court).

Some of the residents also say they were told that if they wanted to stay in their homes they would have to fix them up; insurance was too difficult to obtain unless the repairs were made. Several residents made improvements. Donald Bain, who had lived at 239 Kapili St. for twenty years, rewired his two-story house; Frank Sarivalas, a single father of two, repaired his roof and floors and cleared underbrush for a lawn; Linda Lehmann, who had recently moved into the neighborhood after four earlier evictions in Waikiki, all due to development, built a fence and repainted her apartment.

The Property Managers raised some rents, in some cases without giving residents the required 45-day notice for a rent increase. Bain and his wife, Lizabeth Ball, saw their rent jump from $500 a month to $1,500. Other tenants complained of having rents raised three or more times within a few months or of having to pay more rent than had originally been agreed upon.

On Nov. 28, 1990, Steve Cohen, the real estate broker who had bought the land for Pensee—and turned himself into his company’s number one broker in the country in the process—sent Moore a letter stating, “A new directive has come from Japan.” The letter instructed The Property Managers to give all tenants 120 days notice to move. Eviction notices were sent out, but several gave tenants only sixty days to find new homes.

On the eve of the final eviction, a combination press conference, rally and party was held. Liz had weeded and raked a vacant lot for the occasion and several people had set up chairs, tables and Hibachis. Former residents of the area mingled among the holdouts, trading stories from the housing front with those who’d remained. The press weren’t due to show ’til 7 p.m. but by 5:30 p.m. people were mounting soapboxes. John Miller, former chairman of Friends of Tusitala Street, took over the mini P.A. system to act as an impromptu emcee. Many of those who spoke looked faintly embarrassed at first, uninitiated as they were to the art of political speechmaking. But almost all warmed to their topic once they were handed the microphone, and spoke at length about their frustrations, anger and sense of powerlessness. A slew of seasoned activists were on hand—John Witeck, Noel Kent, George Cooper, Marion Kelly, Richard Port, Mike Wilson,Ho‘oipo DeCambra—and they lent an air of professionalism to the proceedings; land struggles were nothing new for them. Not a single politician was present.

Residents who received the notices were shocked. They say that they were angry that they had been lied to, that they had fixed their homes in order to remain in the neighborhood, that they had agreed to massive rent increases only to be told they would have to leave.

Some of the residents decided they would try to fight the eviction. With the help of Gerri Lee of the Waikiki Community Center, Sarivalas organized a community meeting on Dec. 6.

The meeting was attended by property manager Moore, realtor Cohen, then-councilman-elect Andy Mirikitani, Sen. Bert Kobayashi and Philip Doi of the State Office of Consumer Protection. Cohen talked at length about his first impressions of the property. Uninhabitable, he said, citing the presence of cat feces on one property. He and Moore assured residents they would help them relocate. One of the residents asked when Pensee planned to develop the land. Cohen replied he didn’t know, that the company was still in the planning stage and at that point had not applied for any government permits. Another tenant asked Cohen why he had only been given sixty days to vacate. Cohen explained that the unit, a cottage on Tusitala Street, was too old to insure.

Doi questioned the tenants about their notices and informed them that since their homes were to be demolished, under the law they all had 120 days to vacate (if buildings are slated for demolition, the law requires 120 days notice). Doi also told Cohen that because of the sixty-day notices there was a chance that The Property Managers could be found to have committed deceptive trade practices, a civil liability. Cohen then asked what would happen if Pensee decided not to demolish.

At that point, Sen. Kobayashi challenged Cohen. “Did you declare that U.S.A. Pensee had every intention of building a condo?” he asked. Cohen said, yes, he had. “Can a condo be built without houses on the property being demolished?” Kobayashi asked. No, Cohen replied. “Then they will be demolished?” Kobayashi asked. Yes, replied Cohen.

Kobayashi informed the tenants that a 120-day written notice must be given if a company plans to demolish. He added that a lack of insurance is not a valid reason to evict.

The politicians recommended that the residents lodge complaints with the Office of Consumer Protection. Mirikitani told the tenants he would set up a meeting with representatives of Pensee.

The tenants were thrilled that they didn’t have to move right away. One young man got up and testified that Patas had warned him not to show up for the meeting, since those who spoke against the management were likely to be evicted quickly. “But here I am,” he said, “and it looks like we’ve won!”

At 7 p.m., TV crews showed up to get the evening’s sound bytes. Tripods were erected, cameras activated. Reporters wandered through the crowd, looking for subjects to interview. The mauve sky was temporarily cut by blasts of artificial light as residents squinted into unfamiliar lenses and attempted to tell their tales of woe in a minute or less.

Darkness had fallen when the rally’s last speaker, a young man with a look of dazed rapture, asked everyone to join hands and pray. Activists and tenants stood linked together as he intoned, “We are the people of the earth. We are the people that love and care for each other. May that go on and on forever.” With that, the meeting disintegrated into little animated pockets and the barbeque swung into action. Snatches of conversation filled the air: “We did all the wrong things...” “You’re paying how much?” “When are you leaving for the Mainland?” “Is there ketchup?”

The next day (ironically, Dec. 7), four residents who’d volunteered to act on the tenants’ behalf met and formed the Friends of Tusitala Street Committee. The group began to meet on a weekly basis and it grew. Eventually, Miller was elected chairman, Ball was elected vice chairman. Bain, Sarivalas, Lehmann and other area residents Carl Mossman and Michelle Corder were members.

By mid-December, the Friends of Tusitala Street were up and active. They sent notices to everyone in the neighborhood advising them that they didn’t have to move for 120 days. They printed outsized notes for a visually impaired tenant, got a Spanish translator for another and returned again and again to a disabled elderly woman who had difficulty understanding them. They waged a letter-writing campaign, gathered signatures on petitions and researched Waikiki evictions. Members testified at the City Council in favor of a bill that would impose a moratorium on development in Waikiki until the end of the year, at the Legislature for fair housing bills.

The Friends spent a great deal of time getting people to file their complaints against U.S.A Pensee and The Property Managers with the Office of Consumer Protection. The OCP didn’t do too much with the complaints; after the community meeting on Dec. 6, The Property Managers had reissued eviction notices to reflect the 120-day requirement and Commissioner Doi said he felt his office had done all it was prudent to do.

Mirikitani, true to his word, set up a meeting with U.S.A Pensee for Jan. 4. On the day of the meeting, however, no legal representative from Pensee showed up. Subsequent attempts to meet with the company’s representatives also failed.

Thoroughly frustrated, Miller tried to call Pensee’s headquarters in Osaka, Japan. The number he ended up dialing turned out to be the home number of Pensee’s president, Shoji Nakamoto. Miller later learned that the call had incensed Nakamoto; Pensee’s attorneys, the firm of McCorriston, Miho & Miller, informed the tenants that Nakamoto had taken it as a threat. According to Ball and Lee, McCorriston said the call had made Nakamoto want to bring on the bulldozers. McCorriston denies ever mentioning bulldozers at the meeting.

On Jan. 28, Pensee came up with an offer to area residents that contained incentives to move quickly. The plan basically said the sooner you leave, the more compensation you’ll get. To residents who moved by Feb. 28, Pensee offered a three-month rent rebate (paid directly to the next landlord). To residents who moved by March 31, the rebate was good for two months of rent. In addition, the company offered to provide moving assistance and to sign people up for a housing referral service. In return, tenants were made to sign a release against Pensee.

The deal, which was referred to by Pensee’s public relations man Jim Boersema as “the best relocation package ever in Hawaii,” was negotiated between Lee of the Community Center and Pensee’s lawyers and, to a lesser extent, Mayor Frank Fasi’s office and Mirikitani. The deal had no relation to the tenants’ request, which was to be allowed to stay in their homes until Pensee had received preliminary approval for its project from the city.

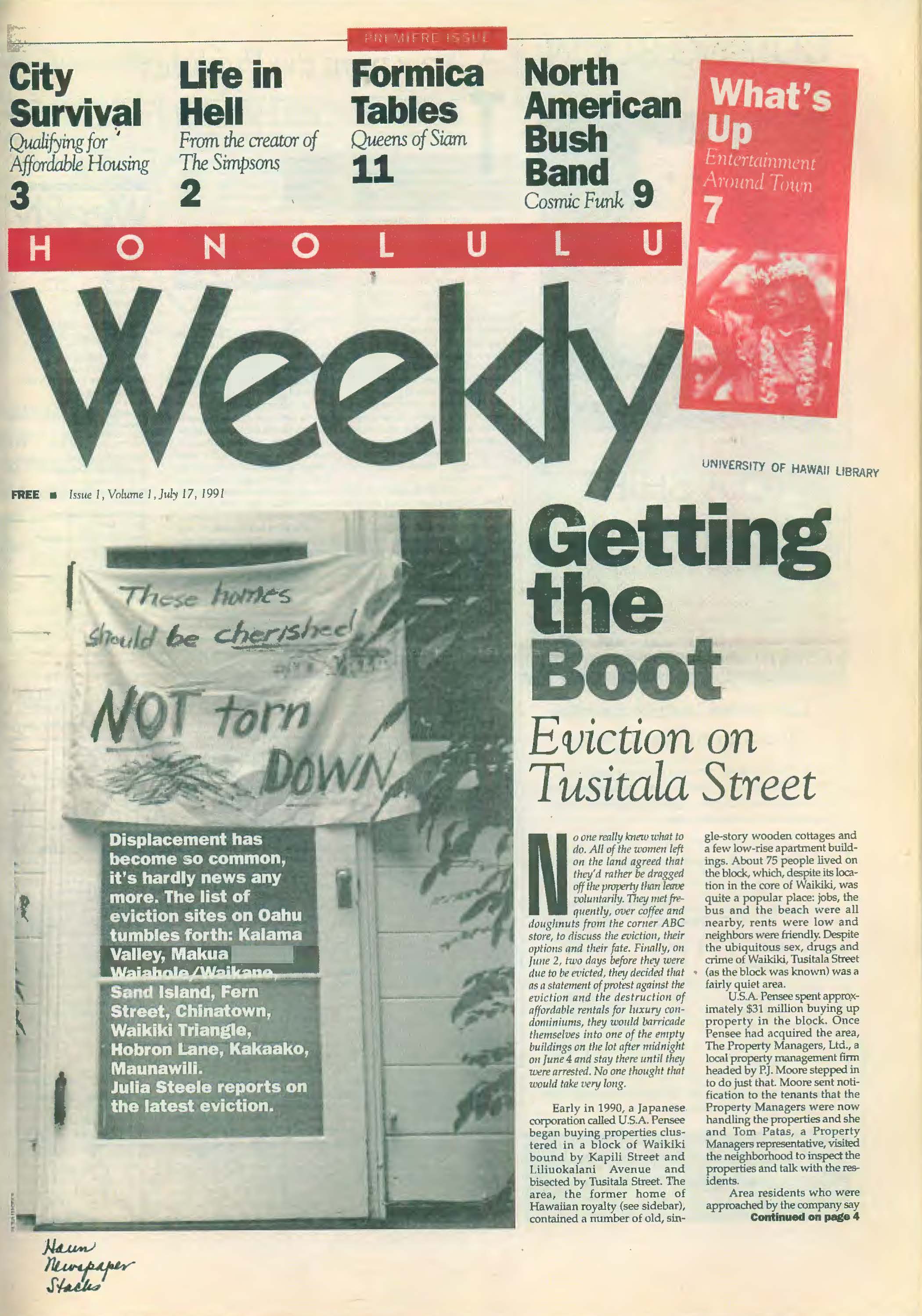

Nonetheless, many residents decided to take the money and leave. Miller, who said the offer was the best they would get, recommended everyone accept it. But a few individuals—Ball, Bain, Lehmann, Sarivalas, Beth Allen and Corder—continued their fight to remain on the land. They were still mad about the way they had been treated and didn’t want the buildings to be tom down until Pensee was given the go-ahead to build. “Why are you going to destroy affordable housing when you can’t build anything on the lot anyway?” Bain asked.

One by one, the residents moved out. Lehmann remembers waking every morning to the sound of hammers and breaking glass as plywood was nailed over main news and doors. March 12, to the tenants’ surprise, the bulldozers arrived and the houses began to go down. On March 16, Ball was arrested at the Sarivalas residence when she refused to leave the premises so the house could be bulldozed. The remaining residents decided they’d better find a lawyer—and fast.

The stars were out and the moon was up. The barbecue was pau. Donald, Liz and their son were loading the U-Haul truck that stood in their driveway. A large woman walking a dog wandered by and stopped to talk to Donald. She wanted to give Donald and Liz $2 million, she said, and, furthermore, she intended to buy back the property from Pensee for $35 million so everyone who’d been evicted could move back. Donald thought she might be serious; George Cooper, who’d overheard the conversation, gently said he wasn’t so sure.

On the other side of the lot, a few people were sitting around smoking, drinking beer and eating potato chips. A portly man who said he was a Vietnam veteran was leading tours up to the roof of one of the walk-ups—he’d erected an apartment for himself there and had managed to get a living room set, a bed and the table onto the roof. It was quite cozy.

Around 10:30 p.m. two men walking in an unsteady manner wandered onto the lot. The more aggressive of the two, a stocky guy with a mustache and a straw hat, quickly launched into a tirade at Donald.

“You went threaten my cousin, you fuckah. You no mess with my family. I came from Kauai to kick your ass.” Donald looked aggravated but hardly worried. The security guard from Pensee wandered over to find out what was going on. By that time the fellow had turned his attention to the veteran. “You. Hey, I talking to you, fuckah. I came from Molokai this morning.” The security guard, a large, calm black man, suggested that maybe the guy should leave. A few people standing nearby wondered about calling the cops, but everyone agreed this was the last night they wanted to invite the police to the property. The security guard finally coaxed the two off the property and they stood across the street, swaying and glowering. Every so often the guy stumbled back to repeat his litany of threats to anyone who’d listen, though for the life of him he couldn’t seem to decide which island he’d arrived from that morning.

At the end of March, the remaining Friends of Tusitala Street hired attorney Robert Merce to represent them. Since several tenants were supposed to be out of their homes by the 31st of that month, Merce immediately went to court and got a temporary restraining order to make sure Pensee did not exercise “self-help” to get people off the property. Merce then filed suit for a preliminary injunction (an indefinitely extended restraining order) that would allow the residents to stay in their homes.

Pensee in turn sued for summary possession to get the tenants off the land. Negotiations between Merce and Pensee’s lawyers proved fruitless.

At the same time, Merce filed a suit in Circuit Court against The Property Managers and Pensee, alleging that the verbal agreements between the tenants and The Property Managers constituted valid and enforceable leases. The suit asked that tenants be allowed to stay in their homes for another two or three years and also asked for an unspecified amount of damages.

In a chamber conference held shortly before the trial on the summary possession case, Judge Francis Yamashita, who was trying the case, basically told Merce that verbal agreements would not hold up in his court. He said he’d ruled against the Waikiki Triangle merchants (in a similar case) and his rulings would be consistent.

Just before the trial, the residents received another blow. On April 26, McCorriston’s firm sent a letter to Merce saying it was likely the tenants would be held liable for the firm’s fees if they went to trial (Yamashita had ruled this way before). Everyone was aware the bill was going to run into the hundreds of thousands. “We took it [the threat] seriously,” said Merce. In the end, the tenants who’d filed the suit and Pensee settled out of court. Under the terms of the agreement, tenants were allowed to stay in their homes until June 4. They would pay no rent for May and the first four days of June and the settlement in the summary possession case would have no bearing upon the suit in Circuit Court.

Meanwhile, at a Waikiki neighborhood board meeting on April 2, Pensee unveiled its plans for the superblock. The luxury twin-tower condominium project would cost $23 million to build and rise to a height of 240 feet. The mauka tower would house 46 units, the makai 101, and the rooftop would feature numerous amenities. Boersema estimated apartments in the complex would be roughly 550 square feet in size and cost half a million dollars.

On April 10, the Waikiki moratorium was approved.

By 11:45 p.m., everyone was utterly exhausted. Linda, Liz, Beth and Michelle—the women who’d decided to stay and be arrested—reconnoitered in Michelle’s apartment. Did they really want to go through the hassle of being arrested? After much discussion and some dissension, everyone decided they would stay. The women found an open apartment on the third floor and moved in to start their subversive slumber party. Liz had bought six baguettes of Shirokiya bread and everyone lay around on the floor, worn out, gnawing on hunks of dough and discussing exactly what they’d do when the sheriffs arrived: Who would stay inside? Would they leave peacefully when the sheriffs told them to, or would they barricade themselves into the apartment and force the law to break down the door? How could they most effectively barricade themselves in?

At midnight, six police vehicles—cars and cushmans—roared into the area. After a minute or two of positioning and conferring, all six roared out. A minute later, a single car returned. Seconds after, it was followed by three cushmans. The same screeching, conferring and departure ensued. The scene was played out four times between 12 and 12:30 a.m. No one really minded the noise since, as is true of most slumber parties, sleep wasn’t on the agenda. But it was infuriating to think of taxpayer monies being used to support such games of intimidation.

The women continued to talk. Beth wanted to make sure that her Bible would be retrieved if she was unable to take it with her when she was arrested. Liz wondered if the statement they were making by being arrested would get across to people. Michelle was worried about the items she had yet to remove from her apartment. Around 2 a.m. Beth grabbed the box of supplies she’d brought—filled with blankets, clothing and a sleeping bag— rummaged through it and pulled forth a blood-red string of firecrackers at least three feet long. “To celebrate the death of Tusitala Street,” she said with a tired smile.

The remaining residents spent the last month at odds. The men were tired of fighting and resigned to leaving. They spent a lot of time drinking beer on the back steps. The women were still desperately trying to find a way to stay. They didn’t seem able to accept that their homes, theirhomes, would soon be reduced to rubble, their gardens to dirt. They spent a lot of time on the phone.

Among everyone, there was a good deal of bitterness about the losing battle they had waged and a sense that their attempts to use the system, to negotiate through politicians and political agencies, had lost them precious time and whatever chance they might have had to stay.

The sheriffs arrived before 8 a.m. They quickly located the apartment the women were in and asked everyone to leave. They then threatened arrest. At that point, Michelle left the premises. She later said she was worried that an arrest might jeopardize the damages suit and give Pensee an easy way out. Liz locked the door behind her. The sheriffs gave everyone five minutes to get off the property and told the women that they were only making it worse for themselves by locking the door. After a short standoff, someone arrived with a sledgehammer and broke down the door with a mighty whack! Liz and Linda were quickly handcuffed and escorted off the premises. Beth had locked herself in the bathroom and the sheriffs broke that door down in a matter of seconds. One grabbed Beth by the arms, the other by the legs, and they dragged the 62-year-old Hawaiian woman off the property, fighting all the way, crying, “No! I don’t want to go! I don’t want to go!” When they had “Auntie,” as they were calling her, at the car, they handcuffed her and drove her to jail. The last resident of Tusitala Street was gone.

At the station, the three were booked, photographed, fingerprinted and charged. After bail was posted, everyone walked across the street to get a cup of coffee and figure out what to do next. It was 9:30 a.m. and Ball bought the morning paper. It contained a short mention of the evening’s rally followed by a statement from Boersema, “If worse comes to worst, they will have to be arrested for trespassing. Obviously we really want to avoid that.”

Postscript: A day after the three women were arrested, U.S.A. Pensee filed a lawsuit charging them, along with Sarivalas, Bain and Corder, with trespassing, libel and slander, “negligent” activities and breach of contract, among other things. The suit alleges the six have “caused damages to Pensee, including but not limited to additional interest charges, lost profits, hold over rent at twice the normal rent, construction delays, attorneys’ fees and costs, in an amount believed to be in excess of $1,000,000, which amount will be proven at the time of trial.”

Home paradise lost

Last June 4, the last night the evicted Tusitala Street residents were legally allowed in their homes, a halau of young girls knelt on a patch of cement in Waikiki and began to chant of Ainahau. They knelt in the shadows of skyscrapers, between two homes destined for destruction, fronted by a vast empty lot and backed by a concrete wall. Their young, clear voices filled the air with words rarely heard in Waikiki today, Hawaiian words that spoke of the sanctity and beauty of the aina. Kau ‘oli‘oli ‘oe i ka la‘ela‘e, O neia ‘aina uluwehiwehi, they cried, and as they chanted, they beat time on their pahus and looked at everyone and no one to hide their shyness.

One hundred years earlier, the ground on which the girls knelt had been home to another young woman, Princess Kaiulani. Kaiulani grew up in a bungalow on Ainahau, a ten-acre estate that covered, roughly, what is today the mauka area between Kaiulani and Liliuokalani Avenues. Ainahau, or “cool place” was named by Kaiulani’s mother, Princess Miriam Likelike, who also lived on the estate with her husband, Kaiulani’s father, Governor Archibald Cleghorn. Landscaping and plants were Cleghorn’s two passions, and he transformed Ainahau into a verdant jungle, replete with date, sago and coconut palms, cinnamon, cypress, mango and teak trees, lotus blossoms and fourteen varieties of hibiscus.

Kaiulani spent happy childhood years at Ainahau. She kept peacocks, played croquet on the lawns, paddled her canoe down Apuakehau stream, which ran from the property out to the surf of Waikiki beach. She spent many hours sitting under Ainahau’s massive banyan tree, talking with Robert Louis Stevenson, who also lived on the property (Tusitala Street was named after Stevenson; “tusitala” is Samoan for storyteller).

But the happiness didn’t last, for the 1890s were not good times for the alii. In 1893, Kaiulani witnessed the overthrow of her aunt, Queen Liliuokalani, and the passing of her kingdom into the hands of men who sought the land to harvest nothing more than power and money.

At 23, Kaiulani died of inflammatory rheumatism. Her father talked of turning Ainahau into a park that would honor his daughter’s memory and provide a complement to Kapiolani Park. When he died in 1910, Cleghorn left Ainahau to the Territory, asking that it be named Kaiulani Park and administered by the Territory. The Territory refused the offer, fearing that the area would be too expensive and troublesome to maintain.

In the 1920s, the land was sold to developers who promised “Care will be taken to preserve as many of the trees as possible in building streets into the famous grove” and “No stores, shops or places of public amusement allowed at Ainahau... Nothing but pretty homes at Ainahau.” A number of small, wooden, single-story homes were constructed. In the ’50s they began to disappear, supplanted by two- or three-story cement walk-ups and, later, by towering tenements built to house Waikiki’s burgeoning population. When the superblock goes up, virtually all of the houses will be gone.

When the chant was over, the girls circled through the crowd, their shyness now readily apparent. At the urging of their kumu hula, they shook hands with their audience: thanks were offered, praises sung, smiles exchanged, even a hug or two traded. Then they filed off, home for dinner and perhaps to do homework and watch TV. Behind them they left a land that will be radically changed the next time they see it, a land waiting to be given over to high-rises, to swimming pools, to luxury apartments priced at $1,000 a square foot, a land left, once again, to men for whom the land has no intrinsic value, only a financial one. All that remains of Ainahau are the words of those who dwelt there:

Wind blowing gently from the sea

Brings the fragrance of lipoa seaweed

Love and delight and perfume from my home

My home, my home paradise

So beautiful is my home

Ainahau in a paradise

Swaying leaves of coconuts

Verdant beauty and fragrant flowers

My home, my home paradise.

—Princess Likelike