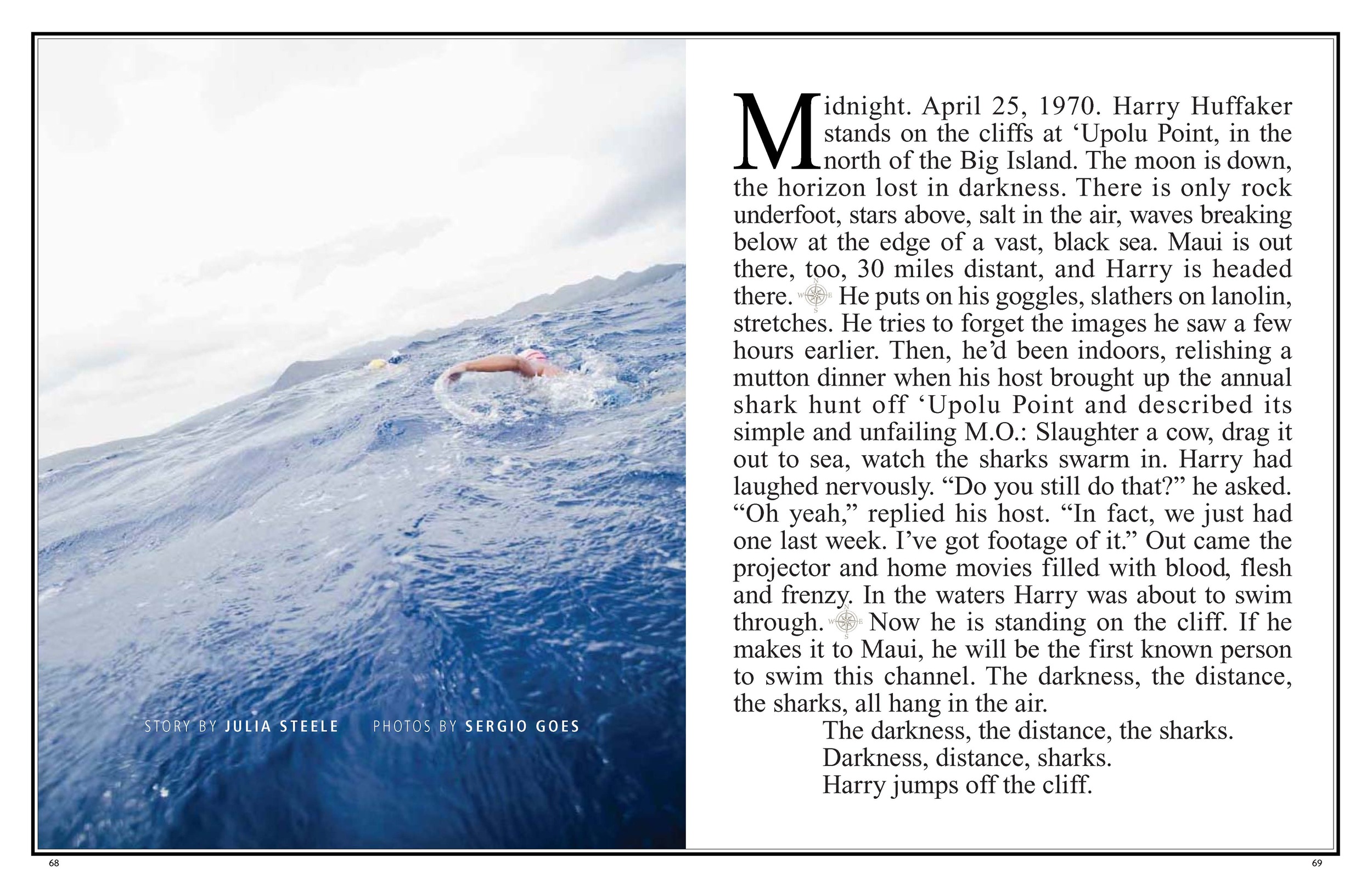

Midnight. April 25, 1970. Harry Huffaker stands on the cliffs at ‘Upolu Point, in the north of the Big Island. The moon is down, the horizon lost in darkness. There is only rock underfoot, stars above, salt in the air, waves breaking below at the edge of a vast, black sea. Maui is out there, too, 31 miles distant, and Harry is headed there.

He puts on his goggles, slathers on lanolin, stretches. He tries to forget the images he saw a few hours earlier. Then he’d been indoors, relishing a mutton dinner when his host brought up the annual shark hunt off ‘Upolu Point and described its simple and unfailing M.O.: Slaughter a cow, drag it out to sea, watch the sharks swarm in. Harry had laughed nervously. “Do you still do that?” he asked. “Oh yeah,” replied his host. “In fact, we just had one last week. I’ve got footage of it.” Out came the projector and home movies filled with blood, flesh and frenzy. In the waters Harry was about to swim through.

Now he is standing on the cliff. If he makes it to Maui, he will be the first known person to swim this channel. The darkness, the distance, the sharks, all hang in the air.

The darkness, the distance, the sharks.

Darkness, distance, sharks.

Harry jumps off the cliff.

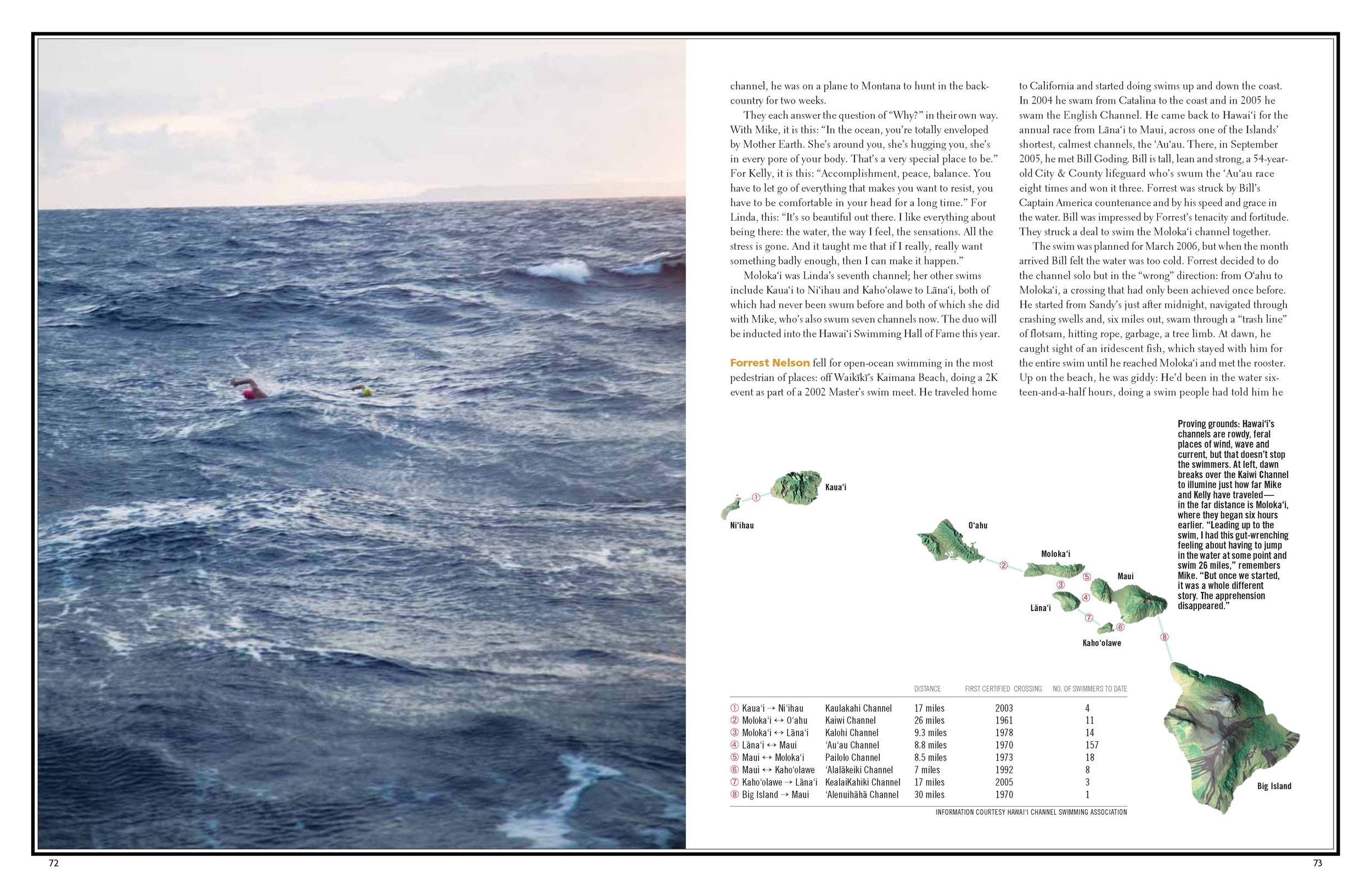

You might think it madness to swim between islands in Hawai‘i, and you might be right. Leaping into dark seas, braving venomous jellyfish and the specter of sharks, getting slammed about by huge swells, fighting current, swimming mile after mile for hour after hour… it’s an utterly improbable quest. The channels between Hawai‘i’s islands are wide and wild places that push and leap, growl and heave. You’re considered hugely valiant even if you paddle them, for God’s sake. And if you swim them?

There are very few people who’ve actually done it, left the shore of one island and swum to another. They have, to a one, fantastic tales to tell, though they’re a self-deprecating bunch. “Just looking into an endless void,” they demur. “It’s monotonous,” laughs Linda Kaiser.

The story of Linda’s Moloka‘i-to-O‘ahu swim last September belies that claim. She set out at midnight on Saturday the 15th to swim the 26-mile Kaiwi Channel with two others. An hour in, she swallowed “something”—a jellyfish, she thinks, though she doesn’t know for sure. Her throat caught fire. Her airways closed up. Her torso cramped and she doubled over in the water. She crawled onto the support boat and curled up in a fetal position. She started convulsing, then retching uncontrollably. It took her nine hours to come out of it.

She could have stopped there. She didn’t. Five days later, she took on the channel again. She’d trained for it, and she wasn’t inclined to give up. But there were complications, the biggest being the currents. If you catch them wrong, they will defeat you—that is an absolute channel swimmers know well. If you run into a three-knot current going out when you’re swimming in at a pace of two knots, you will not make it in. Period. To time the currents right, Linda needed to be coming in to O‘ahu around noon. She wanted to give herself at least fifteen hours for the swim. And so she would need to do most of it in darkness. She left Moloka‘i at 8 at night headed toward Makapu‘u, on the east coast of O‘ahu. It was ten hours of swimming in the black before the dawn arrived. Like being in a sensory-depravation tank, she describes the night, and she had stretches where she didn’t know if she was awake or asleep and if the images that filled her head were hallucinations or dreams. The only light came from the phosphorus that glowed on her skin as she moved through the water. She arrived at Makapu‘u after fifteen hours, swam onto an empty beach, sat among the rocks in the surf and thought in awe, “Damn, I did this.” There are rarely crowds on hand when channel swimmers complete their odysseys. When Forrest Nelson swam up onto the beach on Moloka‘i after swimming from O‘ahu, there was only a lone rooster to greet him. The two walked down the sand, both of them crowing in astonishment.

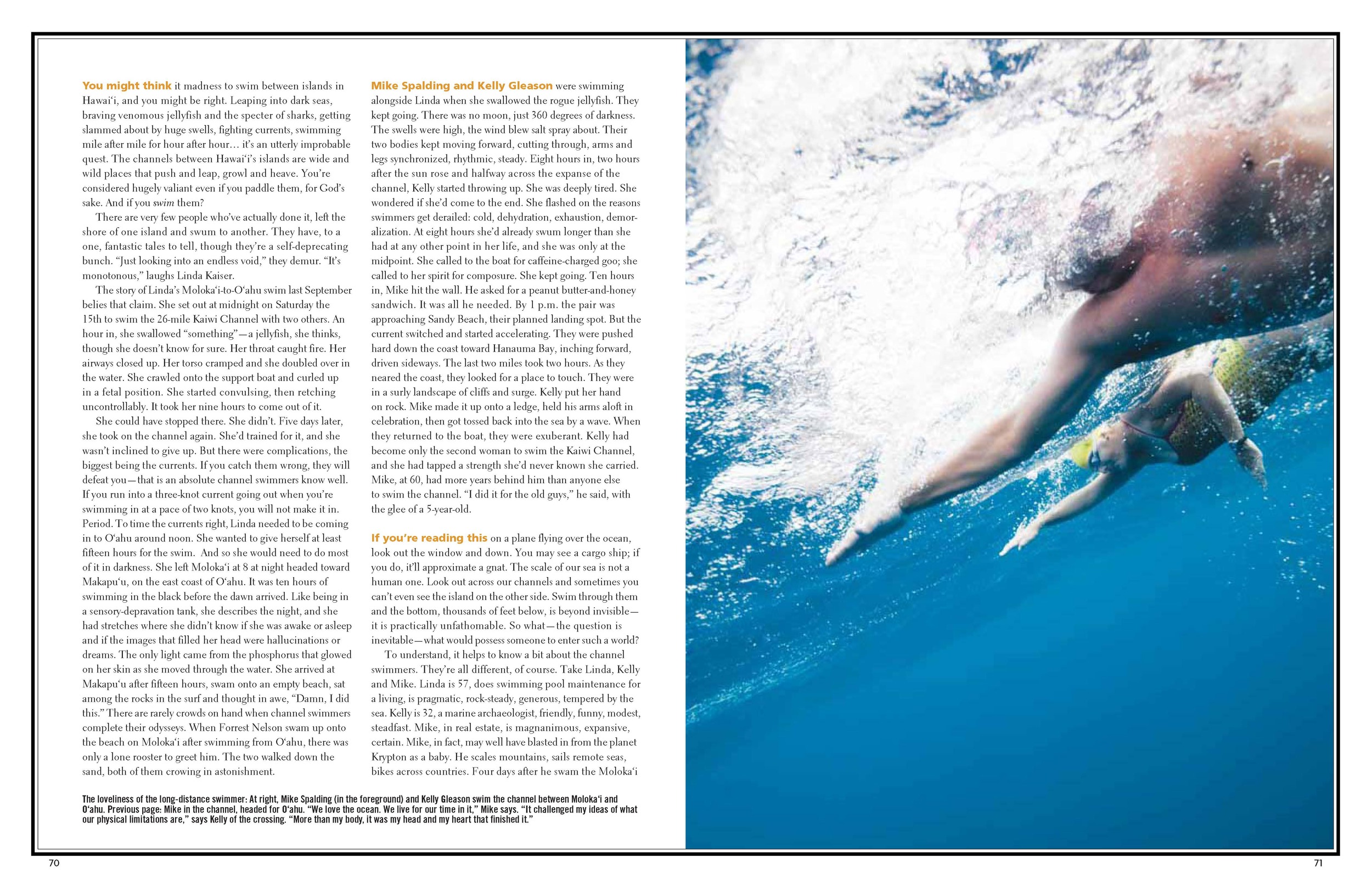

Mike Spalding and Kelly Gleason were swimming alongside Linda when she swallowed the rogue jellyfish. They kept going. There was no moon, just 360 degrees of darkness. The swells were high, the wind blew salt spray about. Their two bodies kept moving forward, cutting through, arms and legs synchronized, rhythmic, steady. Eight hours in, two hours after the sun rose and halfway across the expanse of the channel, Kelly started throwing up. She was deeply tired. She wondered if she’d come to the end. She flashed on the reasons swimmers get derailed: cold, dehydration, exhaustion, demoralization. At eight hours she’d already swum longer than she had at any other point in her life, and she was only at the midpoint. She called to the boat for caffeine-charged goo; she called to her spirit for composure. She kept going. Ten hours in, Mike hit the wall. He asked for a peanut butter-and-honey sandwich. It was all he needed. By 1 p.m. the pair was approaching Sandy Beach, their planned landing spot. But the current switched and started accelerating. They were pushed hard down the coast toward Hanauma Bay, inching forward, driven sideways. The last two miles took two hours. As they neared the coast, they looked for a place to touch. They were in a surly landscape of cliffs and surge. Kelly put her hand on rock. Mike made it up onto a ledge, held his arms aloft in celebration, then got tossed back into the sea by a wave. When they returned to the boat, they were exuberant. Kelly had become only the second woman to swim the Kaiwi Channel, and she had tapped a strength she’d never known she carried. Mike, at 60, had more years behind him than anyone else to swim the channel. “I did it for the old guys,” he said, with the glee of a 5-year-old.

If you’re reading this on a plane flying over the ocean, look out the window and down. You may see a cargo ship; if you do, it’ll approximate a gnat. The scale of our sea is not a human one. Look out across our channels and sometimes you can’t even see the island on the other side. Swim through them and the bottom, thousands of feet below, is beyond invisible—it is practically unfathomable. So what—the question is inevitable—what would possess someone to enter such a world?

To understand, it helps to know a bit about the channel swimmers. They’re all different, of course. Take Linda, Kelly and Mike. Linda is 57, does swimming pool maintenance for a living, is pragmatic, rock-steady, generous, tempered by the sea. Kelly is 34, a marine archaeologist, friendly, funny, modest, steadfast. Mike, in real estate, is magnanimous, expansive, certain. Mike, in fact, may well have blasted in from the planet Krypton as a baby. He scales mountains, sails remote seas, bikes across countries. Four days after he swam the Moloka‘i Channel, he was on a plane to Montana to hunt in the backcountry for two weeks.

They each answer the question of “Why?” in their own way. With Mike, it is this: “In the ocean, you’re totally enveloped by Mother Earth. She’s around you, she’s hugging you, she’s in every pore of your body. That’s a very special place to be.” For Kelly, it is this: “Accomplishment, peace, balance. You have to let go of everything that makes you want to resist, you have to be comfortable in your head for a long time.” For Linda, this: “It’s so beautiful out there. I like everything about being there: the water, the way I feel, the sensations. All the stress is gone. And it taught me that if I really, really want something badly enough, then I can make it happen.”

Moloka‘i was Linda’s seventh channel; her other swims include Kaua‘i to Ni‘ihau and Kaho‘olawe to Läna‘i, both of which had never been swum before and both of which she did with Mike, who’s also swum seven channels now. The duo will be inducted into the Hawai‘i Swimming Hall of Fame this year.

Forrest Nelson fell for open-ocean swimming in the most pedestrian of places: off Waikïkï’s Kaimana Beach, doing a 2K event as part of a 2002 Master’s swim meet. He traveled home to California and started doing swims up and down the coast. In 2004 he swam from Catalina to the coast and in 2005 he swam the English Channel. He came back to Hawai‘i for the annual race from Läna‘i to Maui, across the Islands’ shortest, calmest channel, the ‘Au‘au. There, in September 2005, he met Bill Goding. Bill is tall, lean and strong, a 55-year-old City & County lifeguard who’s swum the ‘Au‘au race eight times and won it three. Forrest was struck by Bill’s Captain America countenance and by his speed and grace in the water. Bill was impressed by Forrest’s tenacity and fortitude. They struck a deal to swim the Moloka‘i Channel together.

The swim was planned for March 2006, but when the month arrived Bill felt the water was too cold. Forrest decided to do the channel solo but in the “wrong” direction: from O‘ahu to Moloka‘i, a crossing that had only been achieved once before. He started from Sandy’s just after midnight, navigated through crashing swells and, six miles out, swam through a “trash line” of flotsam, hitting rope, garbage, a tree limb. At dawn, he caught sight of an iridescent fish, which stayed with him for the entire swim until he reached Moloka‘i and met the rooster. Up on the beach, he was giddy: He’d been in the water sixteen-and-a-half hours, doing a swim people had told him he was crazy to attempt. And he’d done it.

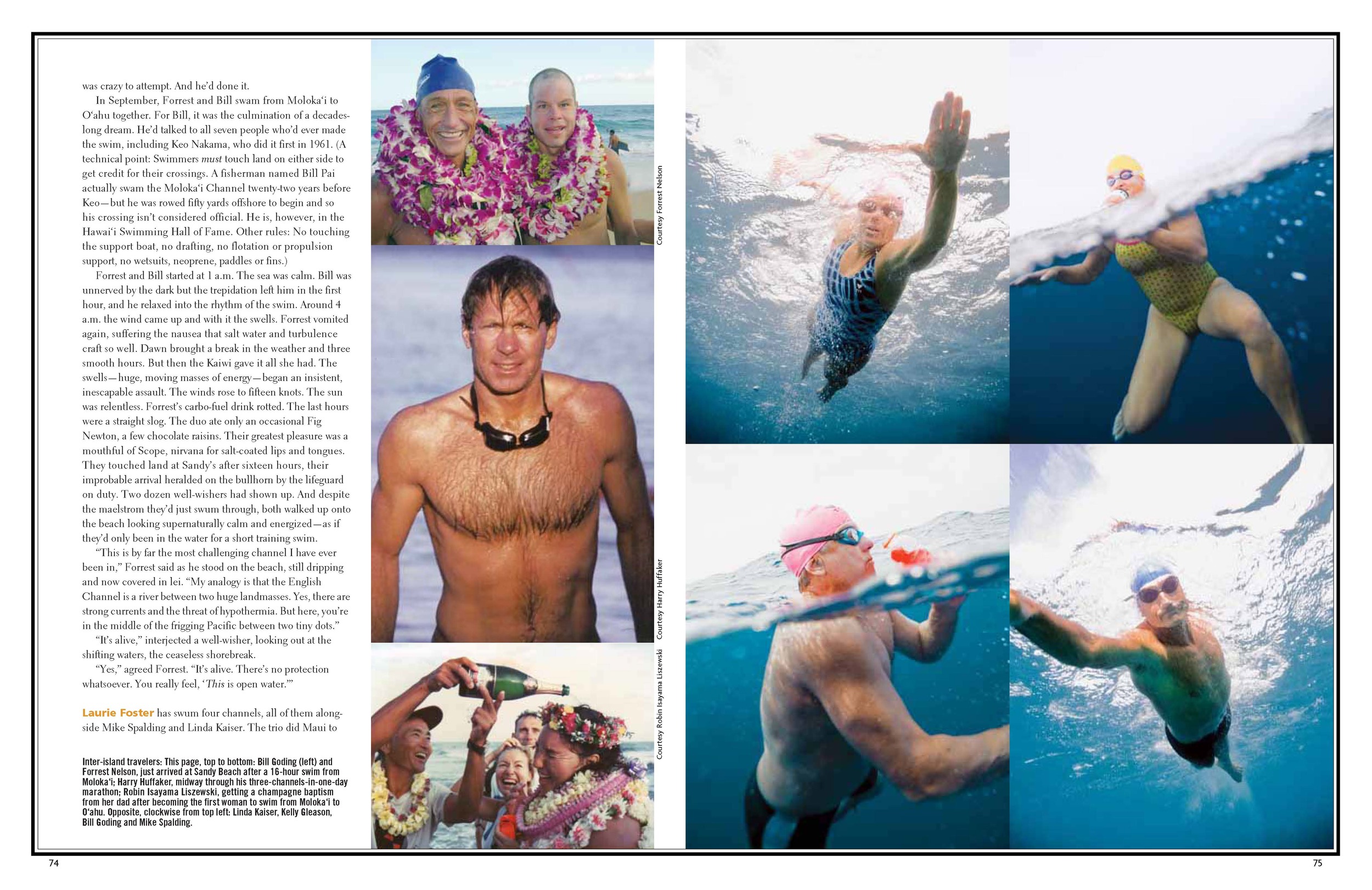

In September, Forrest and Bill swam from Moloka‘i to O‘ahu together. For Bill, it was the culmination of a decades-long dream. He’d talked to all seven people who’d ever made the swim, including Keo Nakama, who did it first in 1961. (A technical point: Swimmers must touch land on either side to get credit for their crossings. A fisherman named Bill Pai actually swam the Moloka‘i Channel twenty-two years before Keo—but he was rowed fifty yards offshore to begin and so his crossing isn’t considered official. He is, however, in the Hawai‘i Swimming Hall of Fame. Other rules: No touching the support boat, no drafting, no flotation or propulsion support, no wetsuits, neoprene, paddles or fins.)

Forrest and Bill started at 1 a.m. The sea was calm. Bill was unnerved by the dark but the trepidation left him in the first hour, and he relaxed into the rhythm of the swim. Around 4 a.m. the wind came up and with it the swells. Forrest vomited again, suffering the nausea that salt water and turbulence craft so well. Dawn brought a break in the weather and three smooth hours. But then the Kaiwi gave it all she had. The swells—huge, moving masses of energy—began an insistent, inescapable assault. The winds rose to fifteen knots. The sun was relentless. Forrest’s carbo-fuel drink rotted. The last hours were a straight slog. The duo ate only an occasional Fig Newton, a few chocolate raisins. Their greatest pleasure was a mouthful of Scope, nirvana for salt-coated lips and tongues.

They touched land at Sandy’s after sixteen hours, their improbable arrival heralded on the bullhorn by the lifeguard on duty. Two dozen well-wishers had shown up. And despite the maelstrom they’d just swum through, both walked up onto the beach looking supernaturally calm and energized—as if they’d only been in the water for a short training swim.

“This is by far the most challenging channel I have ever been in,” Forrest said as he stood on the beach, still dripping and now covered in lei. “My analogy is that the English Channel is a river between two huge landmasses. Yes, there are strong currents and the threat of hypothermia. But here you’re in the middle of the frigging Pacific between two tiny dots.”

“It’s alive,” interjected a well-wisher, looking out at the shifting waters, the ceaseless shore break.

“Yes,” agreed Forrest. “It’s alive. There’s no protection whatsoever. You really feel, ‘This is open water.’”

Laurie Foster has swum four channels, all of them alongside Mike Spalding and Linda Kaiser. The trio did Maui to Kaho‘olawe successfully in 2001, crossing in high winds and large swells; it was the first known time that the channel had been swum in that direction. In 2003, with a fourth swimmer named Tom Robinson, they crossed the 20-mile channel from Kaua‘i to Ni‘ihau, another first. The next swim, two years later, was Kaho‘olawe to Läna‘i, yet another that had never been done before. Laurie thought the channel was ten miles. Flying over from O‘ahu to Maui for the swim, she looked at the airline’s route map of the islands and idly put her finger between Kaua‘i and Ni‘ihau. The distance was a section and a half of her finger. Then she put her finger between Kaho‘olawe and Läna‘i. That was almost two sections. “Hmm,” she thought, “look at that. The map’s wrong.” Five miles across the channel, she found out that the map wasn’t wrong.

“How much more?” she asked the support boat driver, thinking the trio was at about the midpoint.

“Thirteen or fourteen miles,” he replied.

“What did you say?” Laurie looked at Mike, shocked. “How long is this swim?” she asked.

Mike, can do-ness personified, smiled and replied, “Come on, we’re going.”

Laurie, livid, turned to Linda. “I am so pissed right now,” she said.

“Just don’t think about it,” Linda said.

“Don’t think about it?? What the #%@* do you think I’m going to think about for the next eight hours I’m out here?”

The swim was brutal in the end, much longer than anyone had anticipated; it took twelve hours. They finally approached Läna‘i as the sky was darkening, swimming through the ring around the island—where the reef begins, the fish thrive and the sharks feed—as the sun was going down. Mike told everyone to slow down and stay together. Despite the cold in her body and the anger, Laurie took heed. “When Mike gets scared, that’s when I get really scared,” she says. “’Cause he knows so much and he’s Mr. Freewheeling. When he has concern in his voice, there’s reason for concern.” But they saw no sharks and another channel had been completed.

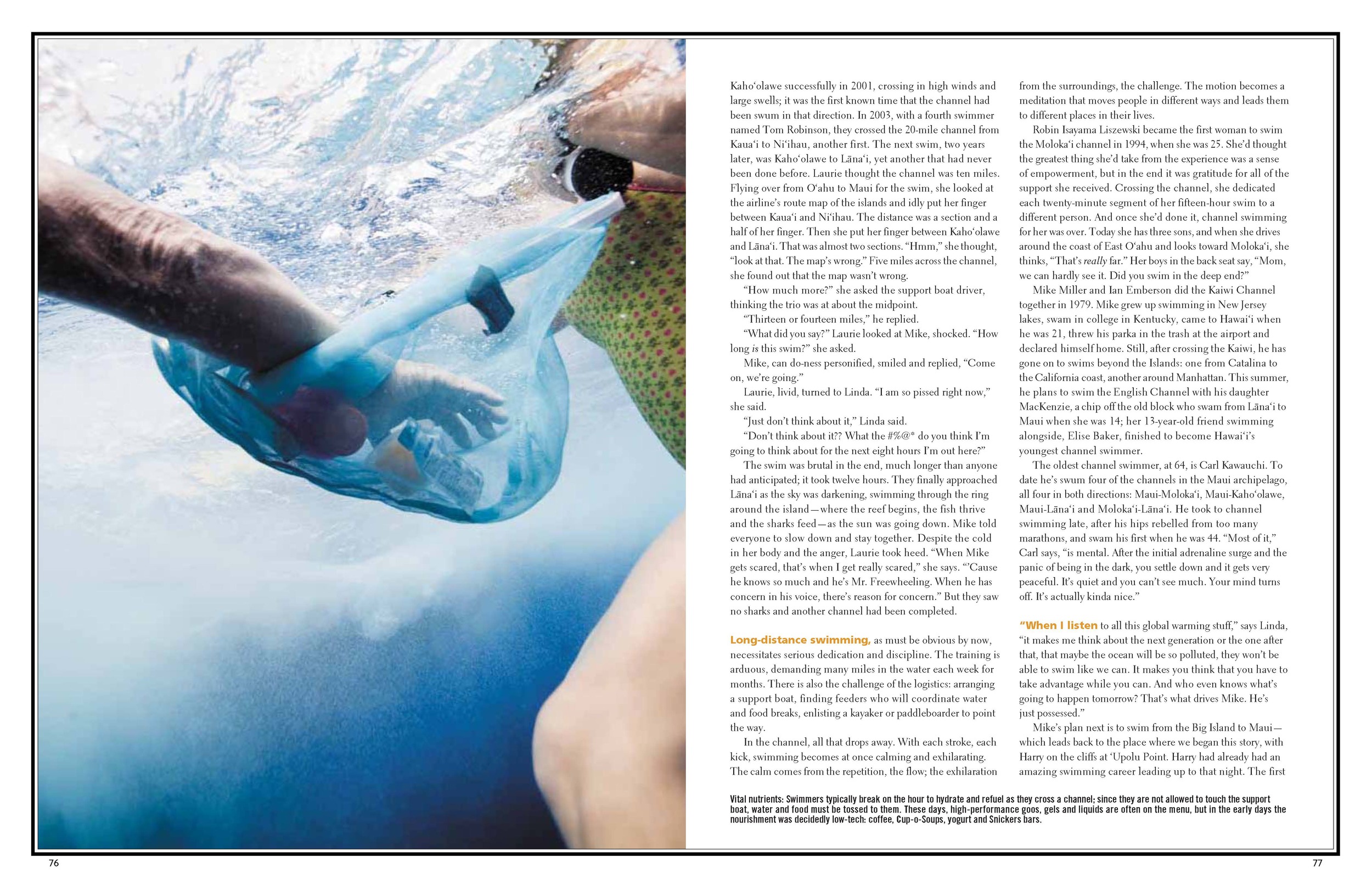

Long-distance swimming, as must be obvious by now, necessitates serious dedication and discipline. The training is arduous, demanding many miles in the water each week for months. There is also the challenge of the logistics: arranging a support boat, finding feeders who will coordinate water and food breaks, enlisting a kayaker or paddleboarder to point the way.

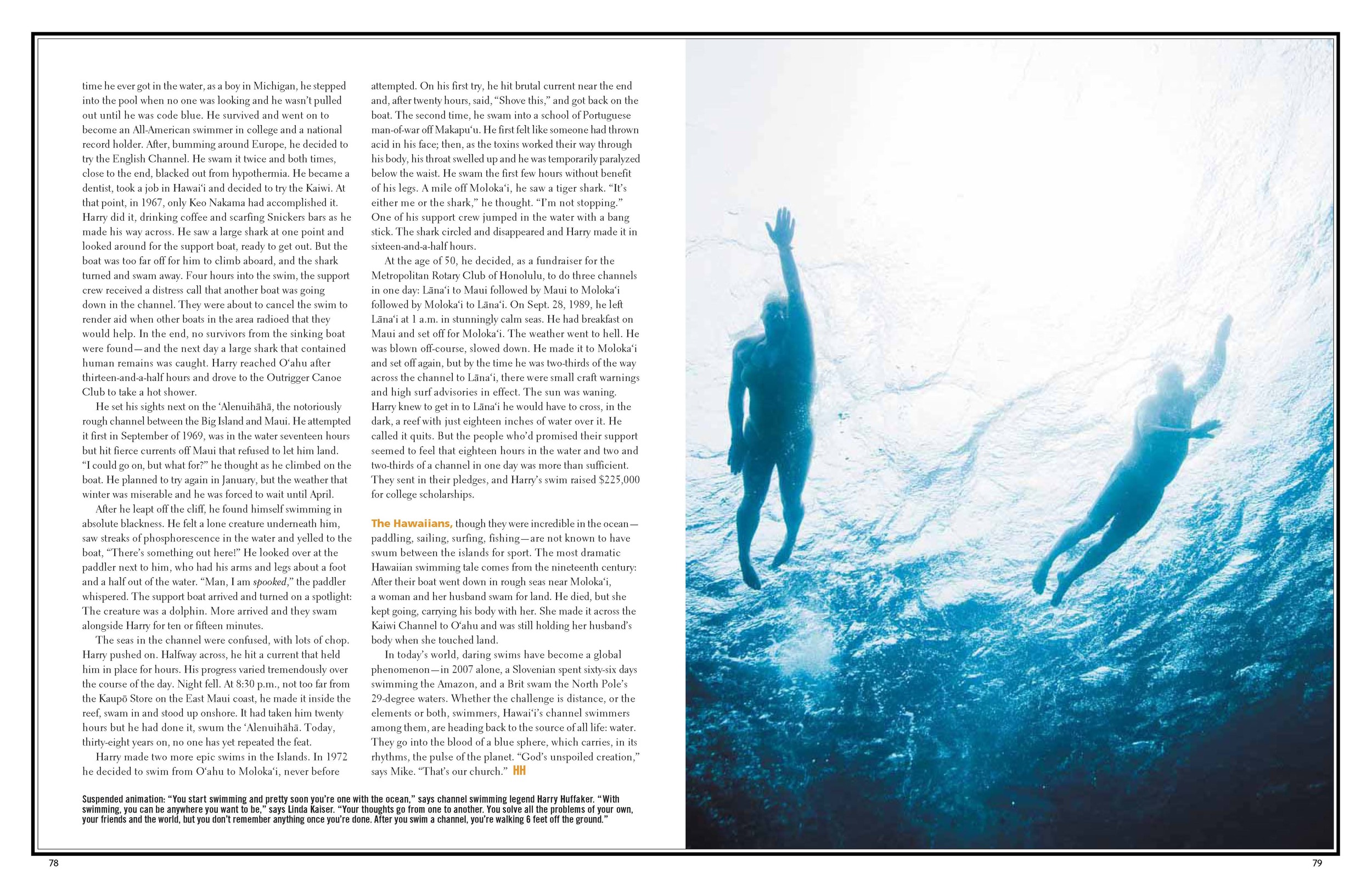

In the channel, all that drops away. With each stroke, each kick, swimming becomes at once calming and exhilarating. The calm comes from the repetition, the flow, the exhilaration from the surroundings, the challenge. The motion becomes a meditation that moves people in different ways and leads them to different places in their lives.

Robin Isayama Liszewski became the first woman to swim the Moloka‘i channel in 1994, when she was 25. She’d thought the greatest thing she’d take from the experience was a sense of empowerment but in the end it was gratitude for all of the support she received. Crossing the channel, she dedicated each twenty-minute segment of her fifteen-hour swim to a different person. And once she’d done it, channel swimming for her was over. Today she has three sons, and when she drives around the coast of East O‘ahu and looks toward Moloka‘i, she thinks, “That’s really far.” Her boys in the back seat say, “Mom, we can hardly see it. Did you swim in the deep end?”

Mike Miller and Ian Emberson did the Kaiwi Channel together in 1979. Mike grew up swimming in New Jersey lakes, swam in college in Kentucky, came to Hawai‘i when he was 21, threw his parka in the trash at the airport and declared himself home. Still, after crossing the Kaiwi, he has gone on to swims beyond the islands: one from Catalina to the California coast, another around Manhattan. This summer, he plans to swim the English Channel with his daughter, a chip off the old block who swam from Lāna‘i to Maui when she was 14; her 13-year-old friend swimming alongside, Elise Baker, finished to become Hawai‘i’s youngest channel swimmer.

The oldest channel swimmer, at 65, is Carl Kawauchi. To date he’s swum four of the channels in the Maui archipelago, all four in both directions: Maui-Moloka‘i, Maui-Kaho‘olawe, Maui-Lāna‘i and Moloka‘i-Läna‘i. He took to channel swimming late, after his hips rebelled from too many marathons, and swam his first when he was 44. “Most of it,” Carl says, “is mental. After the initial adrenaline surge and the panic of being in the dark, you settle down and it gets very peaceful. It’s quiet and you can’t see much. Your mind turns off. It’s actually kinda nice.”

“When I listen to all this global warming stuff,” says Linda, “it makes me think about the next generation or the one after that, that maybe the ocean will be so polluted, they won’t be able to swim like we can. It makes you think that you have to take advantage while you can. And who even knows what’s going to happen tomorrow? That’s what drives Mike. He’s just possessed.”

Mike’s plan next is to swim from the Big Island to Maui—which leads back to the place where we began this story, with Harry on the cliffs at ‘Upolu Point. Harry had already had an amazing swimming career leading up to that night. The first time he ever got in the water, as a boy in Michigan, he stepped into the pool when no one was looking and he wasn’t pulled out until he was code blue. He survived and went on to become an All-American swimmer in college and a national record holder. After, bumming around Europe, he decided to try the English Channel. He swam it twice and both times, close to the end, blacked out from hypothermia. He became a dentist, took a job in Hawai‘i and decided to try the Kaiwi. At that point, in 1967, only Keo Nakama had accomplished it.

Harry did it, drinking coffee and scarfing Snickers bars as he made his way across. He saw a large shark at one point and looked around for the support boat, ready to get out. But the boat was too far off for him to climb aboard, and the shark turned and swam away. Four hours into the swim, the support crew received a distress call that another boat was going down in the channel. They were about to cancel the swim to render aid when other boats in the area radioed that they would help. In the end, no survivors from the sinking boat were found—and the next day a large shark that contained human remains was caught. Harry reached O‘ahu after thirteen-and-a-half hours and drove to the Outrigger Club to take a hot shower.

He set his sights next on the ‘Alēnuihaha, the notoriously rough channel between the Big Island and Maui. He attempted it first in September of 1969, was in the water seventeen hours but hit fierce currents off Maui that refused to let him land. “I could go on but what for?” he thought as he climbed on the boat. He planned to try again in January, but the weather that winter was miserable, and he was forced to wait until April.

After he leapt off the cliff, he found himself swimming in absolute blackness. He felt a lone creature underneath him, saw streaks of phosphorescence in the water and yelled to the boat, “There’s something out here!” He looked over at the paddler next to him, who had his arms and legs about a foot and a half out of the water. “Man, I am spooked,” the paddler whispered. The support boat arrived and turned on a spotlight: The creature was a dolphin. More arrived and they swam alongside Harry for ten or fifteen minutes.

The seas in the channel were confused, with lots of chop. Harry pushed on. Halfway across, he hit a current that held him in place for hours. His progress varied tremendously over the course of the day. Night fell. At 8:30 p.m., not too far from the Kaupo Store on the East Maui coast, he made it inside the reef, swam in and stood up onshore. It had taken him twenty hours but he had done it, swum the ‘Alēnuihaha. Today, thirty-eight years on, no one has yet repeated the feat.

Harry made two more epic swims in the Islands. In 1972 he decided to swim from O‘ahu to Moloka‘i, never before attempted. On his first try, he hit brutal current near the end and, after twenty hours, said, “Shove this” and got back on the boat. The second time, he swam into a school of Portuguese man-of-war off Makapu‘u. He first felt like someone had thrown acid in his face; then, as the toxins worked their way through his body, his throat swelled up and he was temporarily paralyzed below the waist. He swam the first few hours without benefit of his legs. A mile off Moloka‘i, he saw a tiger shark. “It’s either me or the shark,” he thought. “I’m not stopping.” One of his support crew jumped in the water with a bang stick. The shark circled and disappeared and Harry made it in sixteen-and-a-half hours.

At the age of 50, he decided, as a fundraiser for the Metropolitan Rotary Club of Honolulu, to do three channels in one day: Lāna‘i to Maui followed by Maui to Moloka‘i followed by Moloka‘i to Läna‘i. On Sept. 28, 1989, he left Läna‘i at 1 a.m. in stunningly calm seas. He had breakfast on Maui and set off for Moloka‘i. The weather went to hell. He was blown off course, slowed down. He made it to Moloka‘i and set off again, but by the time he was two-thirds of the way across the channel to Läna‘i, there were small craft warnings and high surf advisories in effect. The sun was waning. Harry knew to get in to Läna‘i he would have to cross, in the dark, a reef with just eighteen inches of water over it. He called it quits. But the people who’d promised their support seemed to feel that eighteen hours in the water and two and two-thirds of a channel in one day was more than sufficient. They sent in their pledges, and Harry’s swim raised $225,000 for college scholarships.

The Hawaiians, though they were incredible in the ocean—paddling, sailing, surfing, fishing—are not known to have swum between the islands for sport. The most famous Hawaiian swimming tale comes from the nineteenth century: After their boat went down in rough seas, a woman and her husband swam for land. He died, but she kept going, carrying his body with her. She made it across the Kaiwi Channel to O‘ahu, covering 25 miles and still holding her husband when she touched land.

In today’s world, daring swims have become a global phenomenon—in 2007 alone, a Slovenian spent sixty-six days swimming the Amazon and a Brit swam the North Pole’s 29-degree waters. Whether the challenge is distance or the elements or both, swimmers, Hawai‘i’s channel swimmers among them, are heading back to the source of life: water. They go into the blood of a blue sphere, which carries, in its rhythms, the pulse of the planet. “God’s unspoiled creation,” says Mike. “That’s our church.”