France. 1985. Jean-Charles Cuillandre is a budding young oceanographer with dreams of being the next Jacques Cousteau and plans for a vie en rose of adventure and discovery. Hawai‘i? All he knows of the place is Magnum P.I. and windsurfing. But that’s about to change.

One day Cuillandre reads an article about a telescope France is building, with Canada and Hawai‘i, on the summit of Mauna Kea. In an instant his whole perception of the Islands shifts. Simply a playground? Mais non! Hawai‘i, he learns, is home to cutting-edge science. Sea is replaced by sky. Cuillandre studies everything he can to prepare for a life in astronomy: computers, engineering, arcane instrumentation. And luck of luck, he is given an assignment to come to Hawai‘i for a year in 1995 to install a sixteen-megapixel camera on the Canada-France-Hawai‘i (CFH) telescope.

The first time he actually stands on the summit of Mauna Kea, he is amazed. Then and there he decides to make a film about the mountain. It becomes his great passion. How to capture the grand sweep of its moods: the racing clouds, the shifting light, the passing shadows, the emerging starlight? Photography, he discovers, is too static. But time-lapse photography: Eureka! Take a series of images over a number of hours, animate them at twenty-four frames per second and in less than half a minute, you can see the mountain alive: the rotation of the earth, the sky changing from blue to black and back, the telescopes turning, opening, closing.

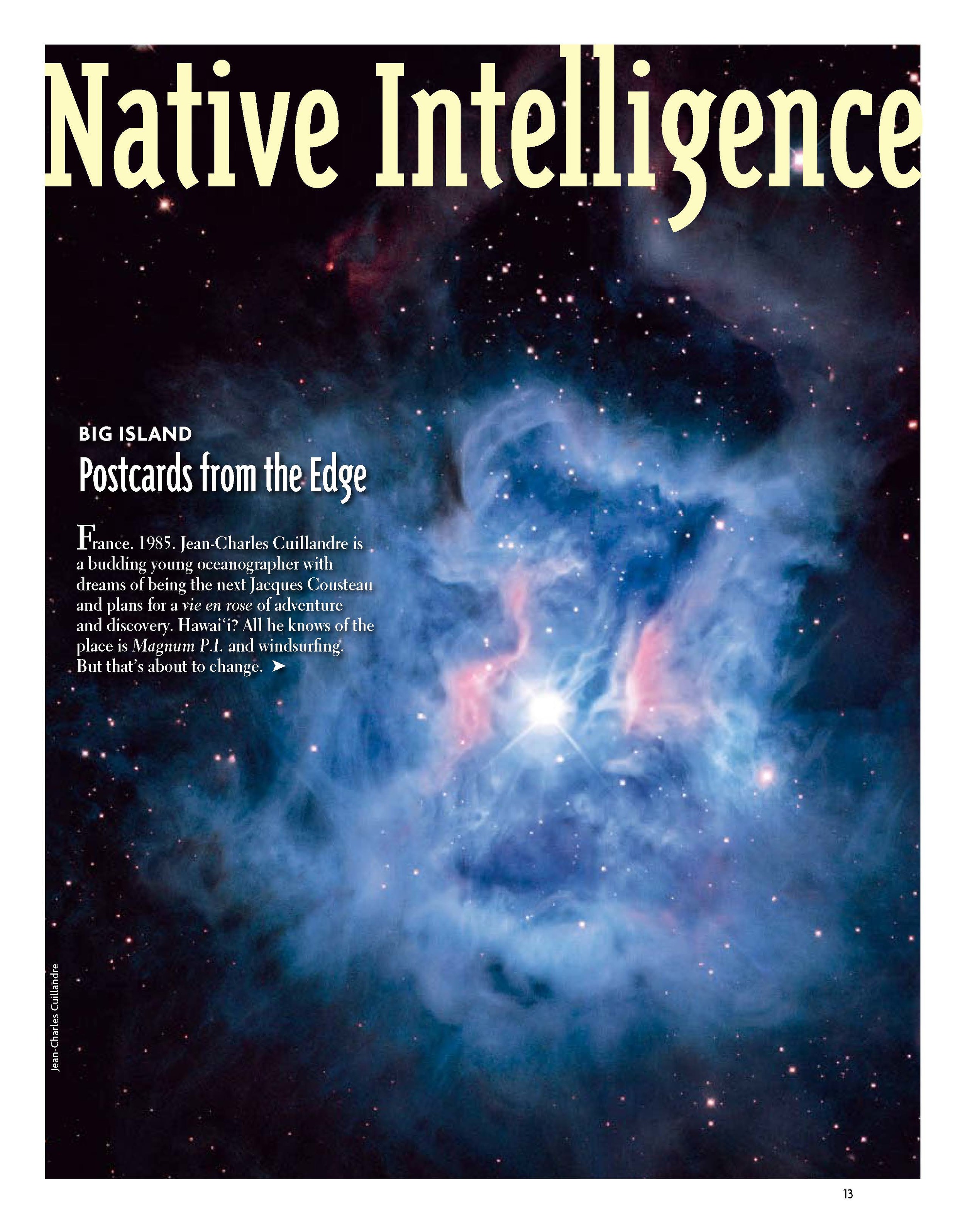

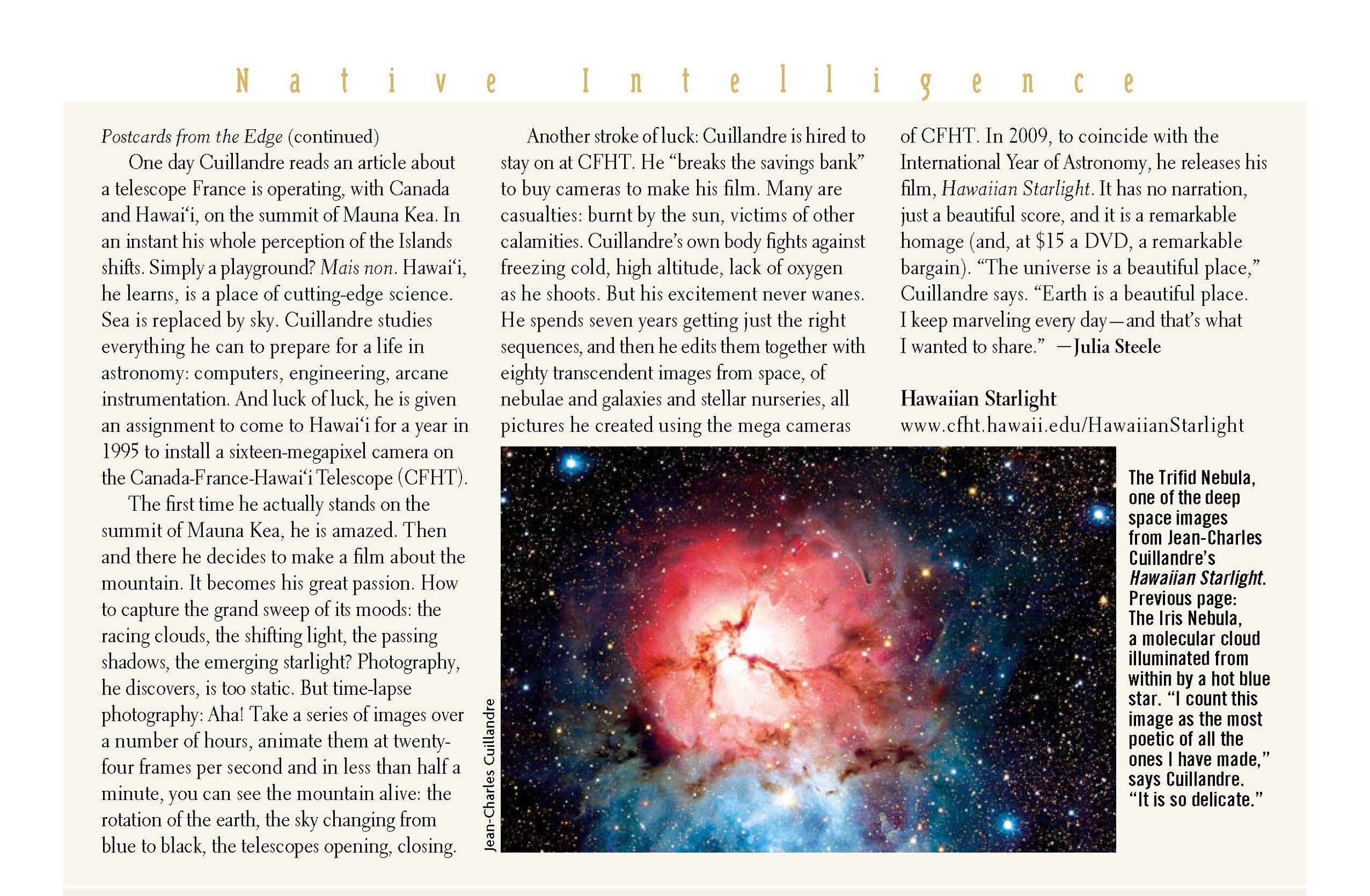

Another stroke of luck: Cuillandre is hired to stay on at CFH. He “breaks the savings bank” to buy cameras to make his film. Many are casualties: burnt by the sun, victims of other calamities. Cuillandre’s own body fights against freezing cold, high altitude, lack of oxygen as he shoots. But his excitement never wanes. He spends seven years getting just the right sequences, and then he edits them together with eighty transcendent images from space, of nebulas and galaxies and stellar nurseries, all pictures he created using the mega cameras of CFH. In 2009, to coincide with the International Year of Astronomy, he releases his film, Hawaiian Starlight. It is a remarkable homage (and, at $15 a DVD, a remarkable bargain). “The universe is a beautiful place,” he says. “Earth is a beautiful place. I keep marveling every day—and that’s what I wanted to share.”