In Japan Dr. Yosihiko Sinoto has often been compared to the world’s best-known archaeologist, the whip- and wise-cracking matinee idol Indiana Jones. The comparison evokes Sinoto’s delighted laugh to this day. Pressed on whether it has any merit, he’ll simply say, “That’s a movie.” He prefers to refer to himself as “a ditch digger.” In fact, he muses, that might be why he’s now outlived his two younger brothers and will turn 90 on September 3: All that ditch digging keeps a body strong. Sinoto is adamant when he emphasizes that to be an archaeologist one must dig. Hands in the dirt. You must handle the artifacts, feel them.

He is in his office at Bishop Museum when he says this. It’s a long, narrow room crammed with boxes, cases, books and papers, all of it testimony to Sinoto’s history with the museum. It’s a history that began over half a century ago when, heading from Tokyo to Berkeley via Hawai‘i, he stopped off to spend a month on an archaeological dig at South Point on Hawai‘i Island. He’d docked in Honolulu aboard the SS President Wilson; to get to Hawai‘i Island he headed to Honolulu Airport, where he’d been instructed to get on the “Kona plane”—a phrase he misheard as “corner plane.” Comic confusion ensued, along with a flight to Hilo and many hours on the road, but finally he made it to South Point. There he joined a dig led by Dr. Kenneth Emory—a dig to which he would ultimately devote many months, a dig that would yield an unprecedented 3,500 fishhooks and answers about the earliest Hawaiians’ arrival in the Islands, a dig that would lay the foundation of Sinoto’s career and his life of adventure in Polynesia.

Remote Pacific islands have been greatly romanticized, perhaps for obvious reasons: clear lagoon waters, intricate jungles, radiant light. But a photo on a travel agent’s wall doesn’t convey the full reality. Those same islands, beautiful as they truly are, can be hot, humid, sometimes lacking in food and drinking water, vulnerable to powerful storms, often treacherous to land upon and extremely isolated.

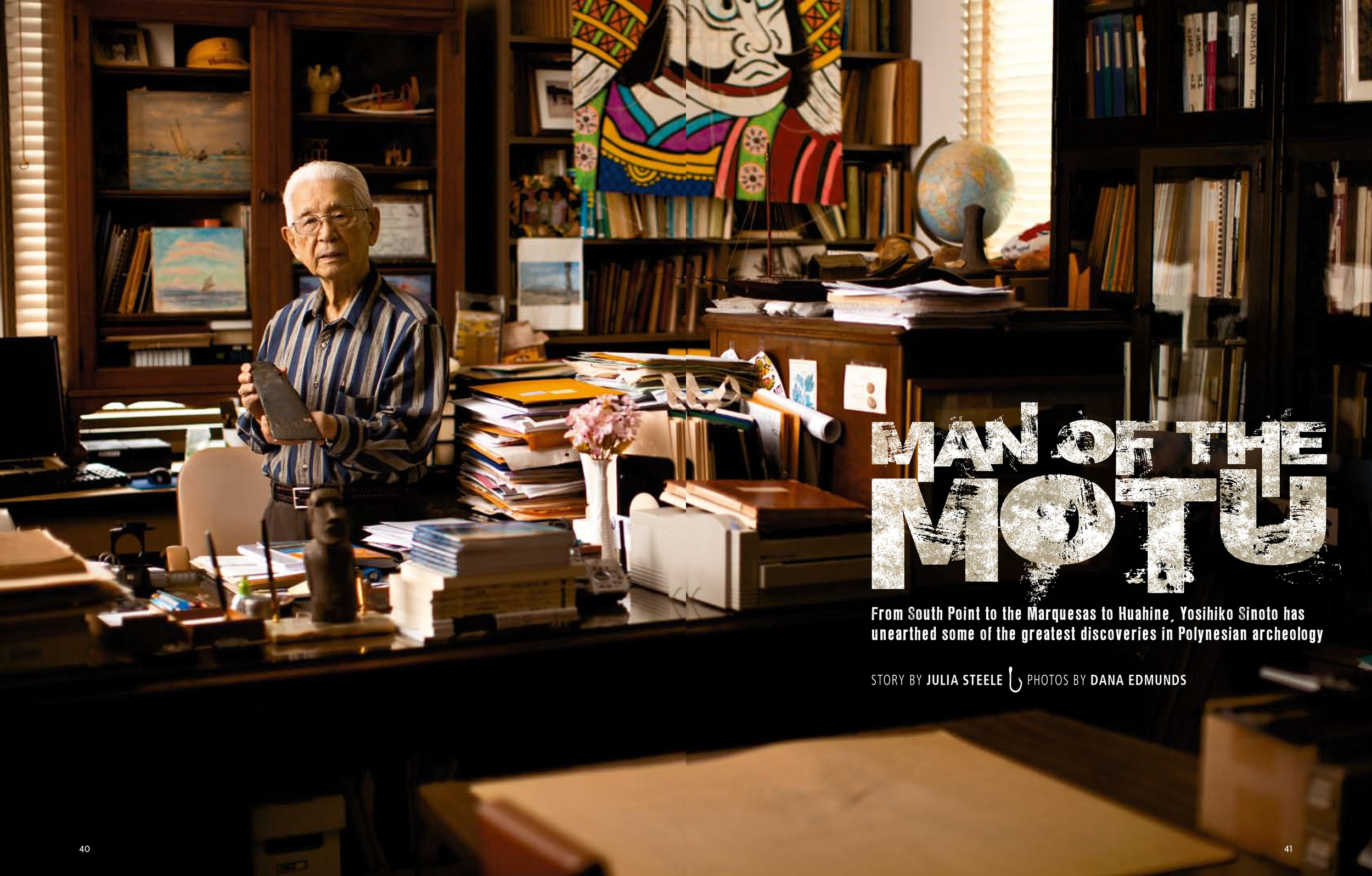

This is the world in which Sinoto has made his name. He took his first trip to Tahiti in 1960 and to the Marquesas in 1963. To get to the Marquesas in those days meant boarding a copra ship in Papeete and threading your way through the seventy-seven atolls of the Tuamotu archipelago—“like that, like that, like that,” he says, laughing as he zigzags his hands to trace the trip. The ship stopped at a dozen or so atolls along the way to pick up copra. The first atoll Sinoto ever landed on was in the western part of the archipelago, Makatea. He remembers his first thought: The land was so low, a mere two meters above sea level. There was a forbidding ocean pass to get to it, Sinoto recalls; later, people on the ship told him that others attempting to make their way through had capsized and died. “I said, ‘Oh my goodness, why did I come here? I’ll never come back again.’” He laughs at the memory. “Next year I was back again.”

Nothing, not even the terrors of the sea, could snuff out Sinoto’s curiosity. In this he may be more like another fictional character, a detective who was a master at using the little gray cells to figure out just what, exactly, was at the bottom of the mystery. “Yeah, it’s kind of a detective work, archaeology,” Sinoto agrees. “For the last fifty or sixty years, I’ve had the same research objective: to find out where the Hawaiians came from, when and how.” It was those questions that drew him back to the Marquesas year after year. He was convinced—remains convinced—that the Marquesas are “very important” in Hawai‘i’s story and that the first human beings to ever set foot in the Hawaiian Islands came from there, with larger, secondary waves coming later from Tahiti. It’s a theory that has been challenged lately by archaeologists within his own museum, but Sinoto scoffs. Again he returns to the artifacts. Where is their proof? he wants to know of the upstarts. He has his right here in his office: cases filled with replicas of fishhooks and patu (war clubs); pictures of petroglyphs and marae (ancient religious sites), all found by him in the field.

Sinoto’s ability to find artifacts is legendary. On his first day on the Tahitian island of Moorea, in 1960, he was biking with Emory when a glint caught his eye. “Stop! Stop!” he called. He pedaled over to a tree by the side of the road and found an ancient fishhook dangling from its roots. Walking by a load of lava rock in Honolulu one day, Sinoto spotted a thousand-year-old adze in its midst. After a young colleague from Bishop Museum had spent four years on Maui digging for fishhooks without finding a single one, Sinoto visited the fellow’s pit and found a fishhook on the first day. Last October, when Sinoto was honored by the Society for Hawaiian Archaeology, one of his colleagues offered the others a little sage advice: “Don’t walk behind Yosi—you’ll never find anything.” Sinoto’s assistant Shoko laughs as he tells this story and from her desk pulls out a little Plexiglass box that contains a portion of a paper clip—the straight and curved sections broken off in such a way as to make it a perfect little hook. She and Sinoto were walking by one of the museum trailers a few months ago when he’d spied it amidst the detritus strewn on the ground and cried, “Fishhook!” His eyes, even if they are old, remain sharp and perfectly trained.

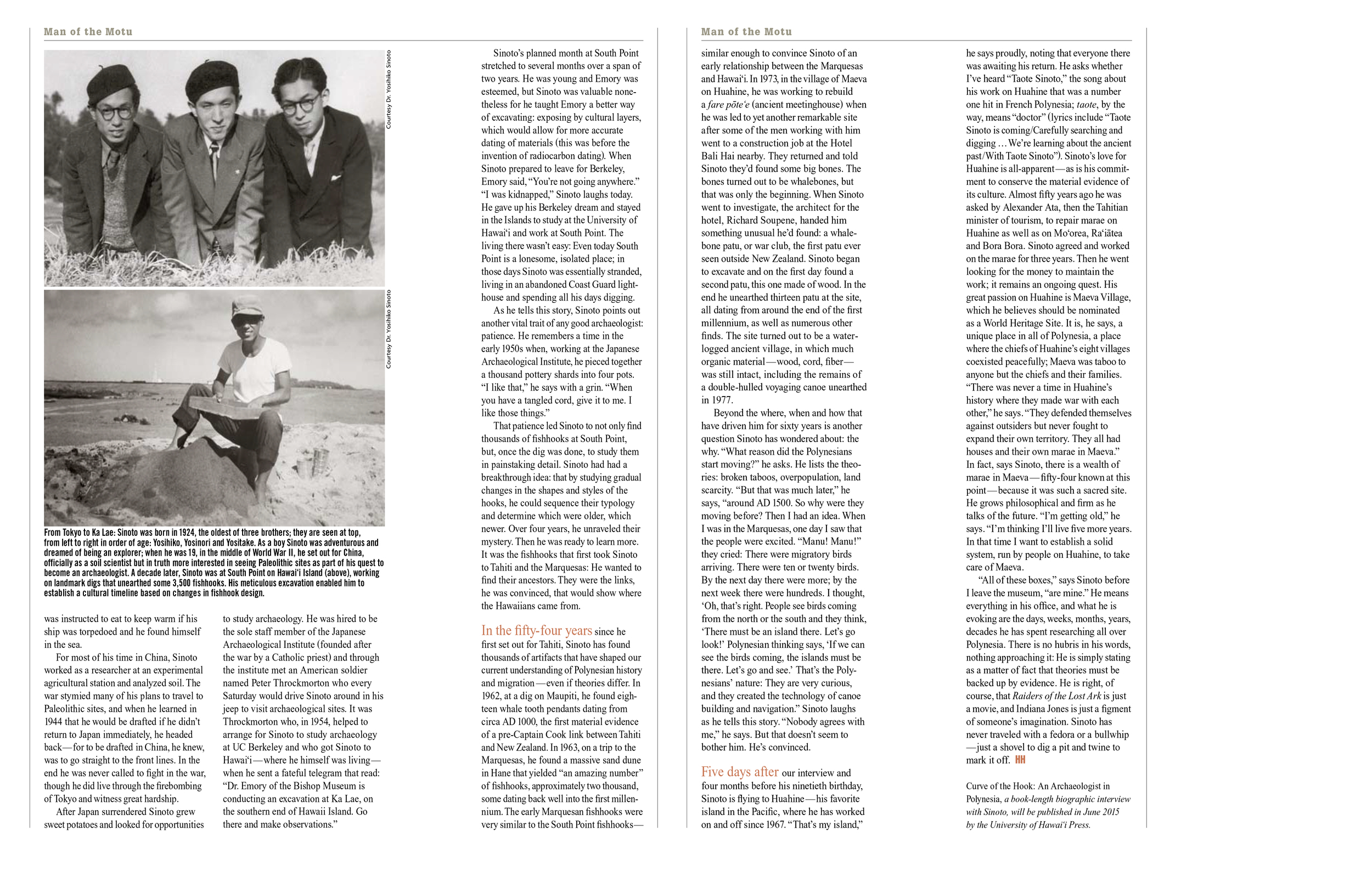

Sinoto was born in Japan in 1924—a year, he notes, with a tragic significance: More Japanese men born in that year were killed in World War II than those born in any other year. He came from an academic family—his father was a genetics scholar at Tokyo Imperial University—and his parents were supportive and nurturing. As a boy he was inspired by the writing of Swedish explorer Sven Hedin and dreamed of a future exploring the jungle in a white pith helmet; in junior high he read an article by an anthropologist who’d been to Inner Mongolia and instantly decided he’d found his calling. He resolved to go to China to study archaeology, and when he was 19 years old, in the midst of the war, he boarded a ferry and set off, carrying a wide belt with chili peppers sewn onto it by his mother—peppers he was instructed to eat to keep warm if his ship was torpedoed and he found himself in the sea.

For most of his time in China, Sinoto worked as a researcher at an experimental agricultural station and analyzed soil. The war stymied many of his plans to travel to Paleolithic sites, and when he learned in 1944 that he would be drafted if he didn’t return to Japan immediately, he headed back—for to be drafted in China, he knew, was to go straight to the front lines. In the end he was never called to fight in the war, though he did live through the firebombing of Tokyo and witness great hardship. After Japan surrendered he grew sweet potatoes and looked for opportunities to study archaeology. He was hired to be the sole staff member of the Japanese Archaeological Institute (founded after the war by a Catholic priest) and through the institute met an American soldier named Peter Throckmorton who every Saturday would drive Sinoto around in his jeep to visit archaeological sites. It was Throckmorton who, in 1954, helped to arrange for Sinoto to study archaeology at UC Berkeley and who got Sinoto to Hawai‘i—where he himself was living—when he sent a fateful telegram that read: “Dr. Emory of the Bishop Museum is conducting an excavation at Ka Lae, on the southern end of Hawaii Island. Go there and make observations.”

Sinoto’s planned month at South Point stretched to several months over a span of two years. He was young and Emory was esteemed, but Sinoto was valuable nonetheless for he taught Emory a better way of excavating: exposing by cultural layers, which would allow for more accurate dating of materials (this was before the invention of radiocarbon dating). When Sinoto prepared to leave for Berkeley, Emory said, “You’re not going anywhere.” “I was kidnapped,” Sinoto laughs today. He gave up his Berkeley dream and stayed in the Islands to study at the University of Hawai‘i and work at South Point. The living there wasn’t easy: Even today South Point is a lonesome, isolated place; in those days Sinoto was essentially stranded, living in an abandoned Coast Guard lighthouse and spending all his days digging.

As he tells this story, Sinoto points out another vital trait of any good archaeologist: patience. He remembers a time in the early 1950s when, working at the Japanese Archaeological Institute, he pieced together a thousand pottery shards into four pots. “I like that,” he says with a grin. “When you have a tangled cord, give it to me. I like those things.”

That patience led Sinoto to not only find thousands of fishhooks at South Point, but, once the dig was done, to study them in painstaking detail. Sinoto had had a breakthrough idea: that by studying gradual changes in the shapes and styles of the hooks, he could sequence their typology and determine which were older, which newer. Over four years, he unraveled their mystery. Then he was ready to learn more. It was the fishhooks that first took Sinoto to Tahiti and the Marquesas: He wanted to find their ancestors. They were the links, he was convinced, that would show where the Hawaiians came from.

In the fifty-four years since he first set out for Tahiti, Sinoto has found thousands of artifacts that have shaped our current understanding of Polynesian history and migration—even if theories differ. In 1962, at a dig on Maupiti, he found eighteen whale tooth pendants dating from circa AD 1000, the first material evidence of a pre-Captain Cook link between Tahiti and New Zealand. In 1963, on the island of Hane, he found a massive sand dune that yielded “an amazing number” of fishhooks, approximately two thousand, some dating back well into the first millennium. The early Marquesan fishhooks were very similar to the South Point fishhooks—similar enough to convince Sinoto of an early relationship between the Marquesas and Hawai‘i. In 1973, in the village of Maeva on Huahine, he was working to rebuild a fare pote (ancient meetinghouse) when he was led to yet another remarkable site after some of the men working with him went to a construction job at the Bali Hai hotel nearby. They returned and told Sinoto they’d found some big bones. The bones turned out to be whalebones, but that was only the beginning. When Sinoto went to investigate, the architect for the hotel, Richard Soupene, handed him something unusual he’d found: a whalebone patu, or war club, the first patu ever seen outside New Zealand. Sinoto began to excavate and on the first day found a second patu, this one made of wood. In the end he unearthed thirteen patu at the site, all dating from around the end of the first millennium, as well as numerous other finds. The site turned out to be a waterlogged ancient village, in which much organic material—wood, cord, fiber—was still intact, including the remains of a double-hulled voyaging canoe unearthed in 1977.

Beyond the where, when and how that have driven him for sixty years is another question Sinoto has wondered about: the why. “What reason did the Polynesian start moving?” he asks. He lists the theories: broken taboos, overpopulation, land scarcity. “But that was much later,” he says, “around AD 1500. So why were they moving before? Then I had an idea. When I was in the Marquesas, one day I saw that the people were excited. “Manu! Manu!” they cried: There were migratory birds arriving. There were ten or twenty birds. By the next day there were more; by the next week there were hundreds. I thought, ‘Oh, that’s right. People see birds coming from the north or the south and they think, ‘There must be an island there. Let’s go look!’ Polynesian thinking says, ‘If we can see the birds coming, the islands must be there. Let’s go and see.’ That’s the Polynesians’ nature: They are very curious, and they created the technology of canoe building and navigation.” Sinoto laughs as he tells this story. “Nobody agrees with me,” he says. But that doesn’t seem to bother him. He’s convinced.

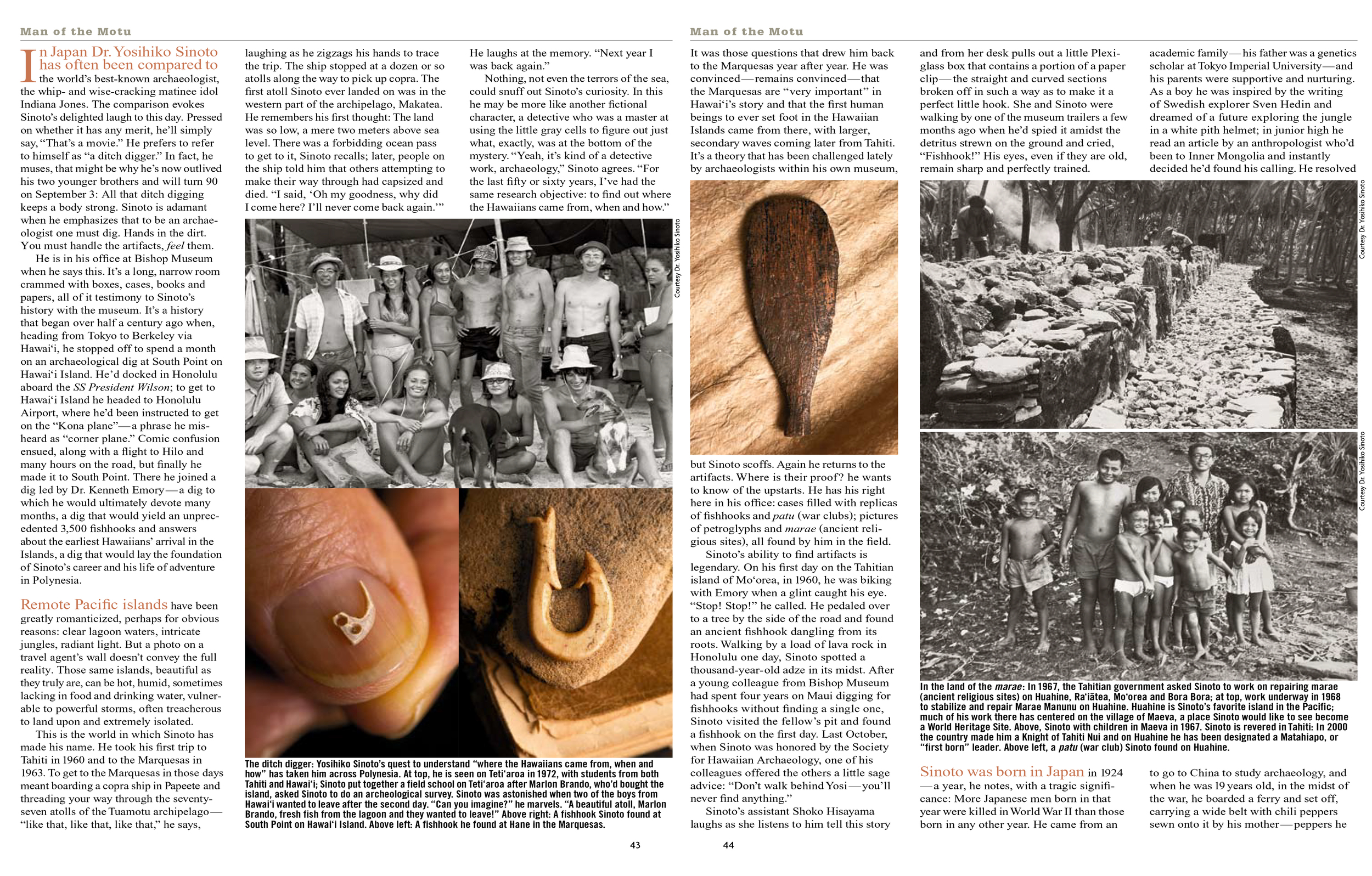

Five days after our interview and four months before his ninetieth birthday, Sinoto is flying to Huahine—his favorite island in the Pacific, where he has worked on and off since 1967. “That’s my island,” he says proudly, noting that everyone there was awaiting his return. He asks whether I’ve heard “Taote Sinoto,” the song about his work on Huahine that was a number one hit in French Polynesia; taote, by the way, means “doctor” (lyrics include “Taote Sinoto is coming/Carefully searching and digging … We’re learning about the ancient past/With Taote Sinoto”). Sinoto’s love for Huahine is all-apparent—as is his commitment to conserve the material evidence of its culture. Almost fifty years ago he was asked by Alexander Ata, then the Tahitian minister of tourism, to repair marae on Huahine as well as on Moorea, Raiatea and Bora Bora. Sinoto agreed and worked on the marae for three years. Then he went looking for the money to maintain the work; it remains an ongoing quest. His great passion on Huahine is Maeva Village, which he believes should be nominated as a World Heritage Site. It is, he says, a unique place in all of Polynesia, a place where the chiefs of Huahine’s eight villages coexisted peacefully; Maeva was taboo to anyone but the chiefs and their families.

“There was never a time in Huahine’s history where they made war with each other,” he says. “They defended themselves against outsiders but never fought to expand their own territory. They all had houses and their own marae in Maeva.” In fact, says Sinoto, there is a wealth of marae in Maeva—fifty-four known at this point—because it was such a sacred site. He grows philosophical and firm as he talks of the future. “I’m getting old,” he says. “I’m thinking I’ll live five more years. In that time I want to establish a solid system, run by people on Huahine, to take care of Maeva.

“All of these boxes,” says Sinoto before I leave the museum, “are mine.” He means everything in his office, and what he is evoking are the days, weeks, months, years, decades he has spent researching all over Polynesia. There is no hubris in his words, nothing approaching it: He is simply stating as a matter of fact that theories must be backed up by evidence. He is right, of course, that Raiders of the Lost Ark is just a movie, and Indiana Jones is just a figment of someone’s imagination. Sinoto has never traveled with a fedora or a bullwhip—just a shovel to dig a pit and twine to mark it off.