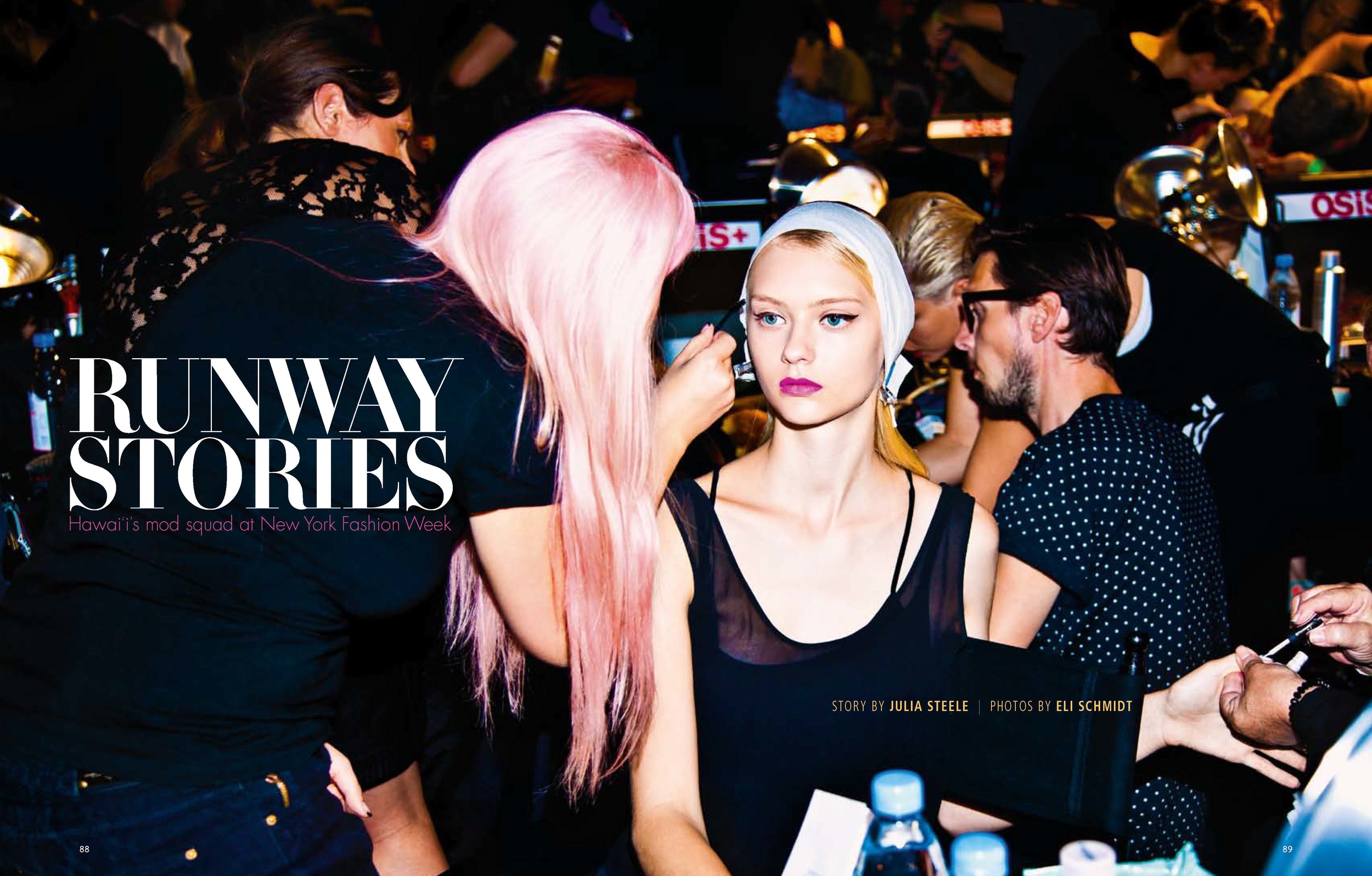

The boys—they are always called boys, never men—stand at one end of a cavernous room, a small army of coifed Adonises in white underwear. Photographers and publicists snap pictures and text wildly, but the boys are impassive; their attention is zeroed in on a silver-haired Japanese woman half their size. She wears all black—Commes des Garçons—and the vivid red painted across her lips is her sole splash of color. She is teaching the boys to walk. “Always stay in the center so the cameras can get you,” she instructs. “When you come to the end of the runway, don’t stop, just pause.” She pulls forward a Frenchman named Alex, and he strides at her behest, hitting his cues. “You,” she tells him, “are so hired.” More instructions and then, “We love you!”—a verbal air kiss before the boys head backstage to dress.

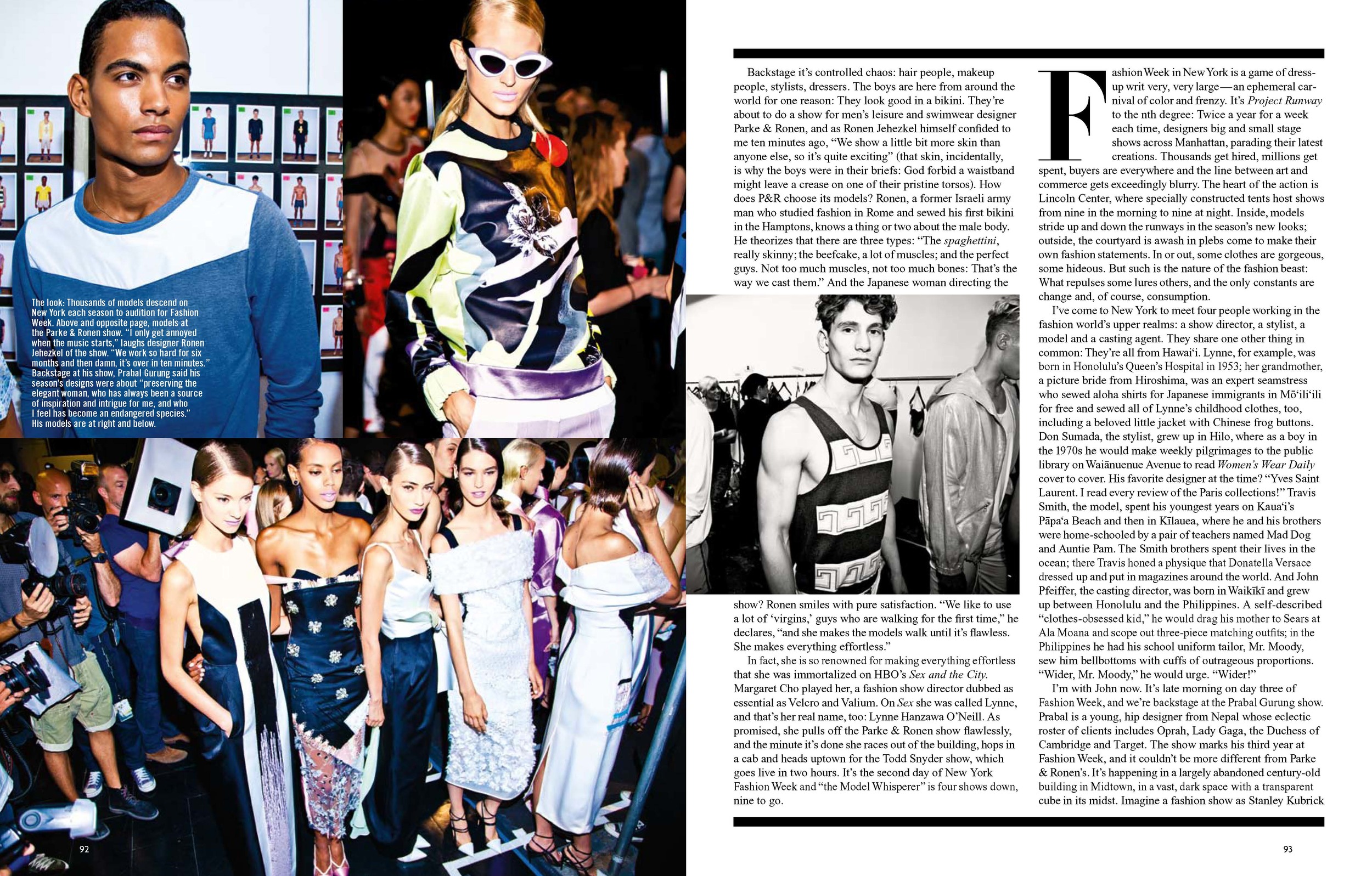

Backstage it’s controlled chaos: hair people, makeup people, stylists, dressers. The boys are here from around the world for one reason: They look good in a bikini. They’re about to do a show for men’s leisure and swimwear designer Parke & Ronen, and as Ronen Jehezkel himself confided to me ten minutes ago, “We show a little bit more skin than anyone else, so it’s quite exciting” (that skin, incidentally, is why the boys were in their briefs: God forbid a waistband might leave a crease on one of their pristine torsos). How does P&R choose its models? Ronen, a former Israeli army man who studied fashion in Rome and sewed his first bikini in the Hamptons, knows a thing or two about the male body. He theorizes that there are three types: “The spaghettini, really skinny; the beefcake, a lot of muscles; and the perfect guys. Not too much muscles, not too much bones: That’s the way we cast them.” And the Japanese woman directing the show? Ronen smiles with pure satisfaction. “We like to use a lot of ‘virgins,’ guys who are walking for the first time,” he declares, “and she makes the models walk until it’s flawless. She makes everything effortless.”

In fact, she is so renowned for making everything effortless that she was immortalized on HBO’s Sex and the City. Margaret Cho played her, a fashion show director dubbed as essential as Velcro and Valium. On Sex she was called Lynne, and that’s her real name, too: Lynne Hanzawa O’Neill. As promised, she pulls off the Parke & Ronen show flawlessly, and the minute it’s done she races out of the building, hops in a cab and heads uptown for the Todd Oldham show, which goes live in two hours. It’s the second day of New York Fashion Week and “the Model Whisperer” is four shows down, nine to go.

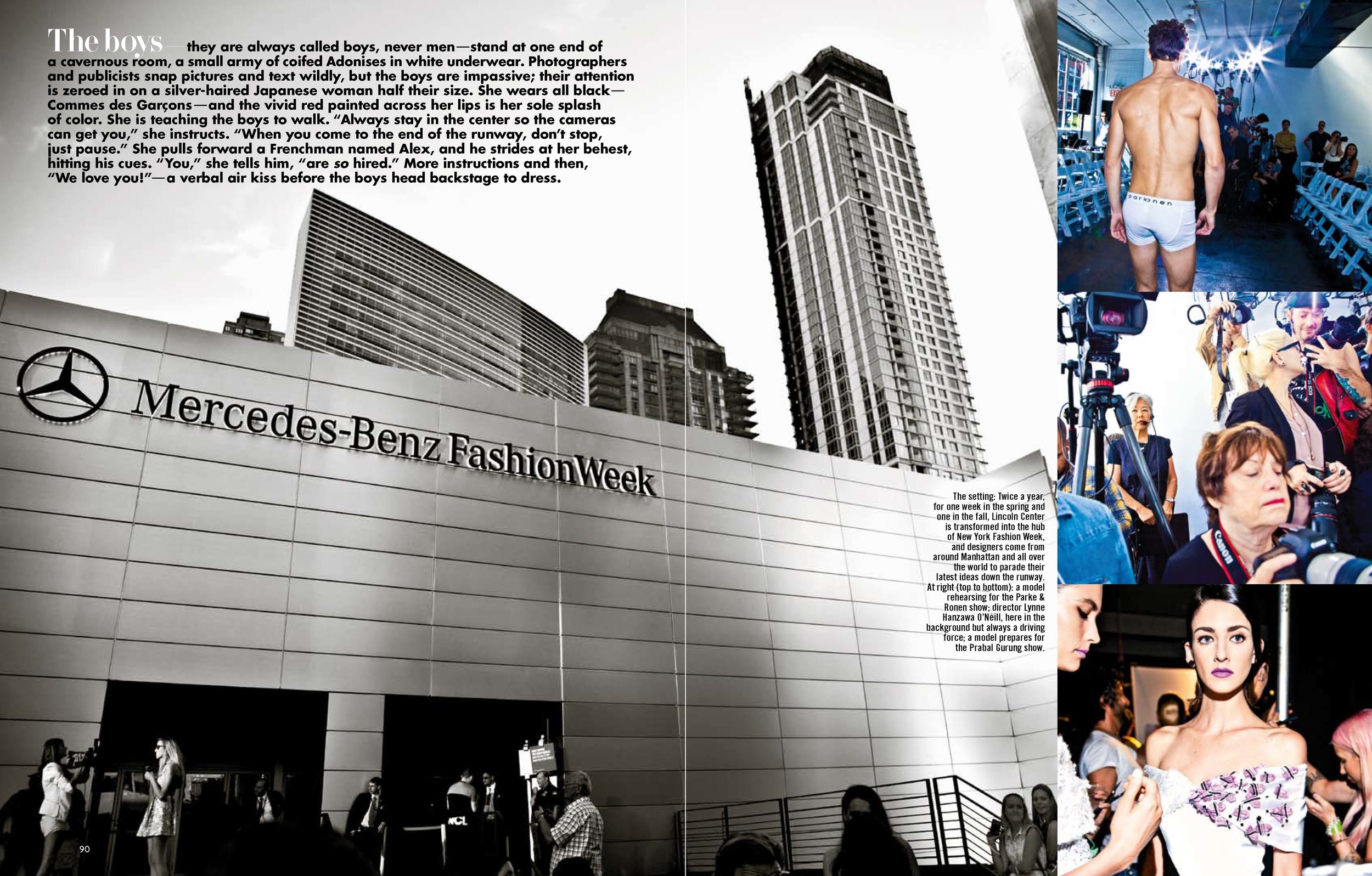

Fashion Week in New York is a game of dress-up writ very, very large—an ephemeral carnival of color and frenzy. It’s Project Runway to the nth degree: Twice a year for a week each time, designers big and small stage shows across Manhattan, parading their latest creations. Thousands get hired, millions get spent, buyers are everywhere and the line between art and commerce gets exceedingly blurry. The heart of the action is Lincoln Center, where specially constructed tents host shows from nine in the morning to nine at night. Inside, models stride up and down the runways in the season’s new looks; outside, the courtyard is awash in plebs come to make their own fashion statements. In or out, some clothes are gorgeous, some hideous. But such is the nature of the fashion beast: What repulses some lures others, and the only constants are change and, of course, consumption.

I’ve come to New York to meet four people working in the fashion world’s upper realms: a show director, a stylist, a model and a casting agent. They share one other thing in common: They’re all from Hawai‘i. Lynne, for example, was born in Honolulu’s Queen’s Hospital in 1953; her grandmother, a picture bride from Hiroshima, was an expert seamstress who sewed aloha shirts for Japanese immigrants in Mö‘ili‘ili for free and sewed all of Lynne’s childhood clothes, too, including a beloved little jacket with Chinese frog buttons. Don Sumada, the stylist, grew up in Hilo, where as a boy in the 1970s he would make weekly pilgrimages to the public library on Waiänuenue Avenue to read Women’s Wear Daily cover to cover. His favorite designer at the time? “Yves Saint Laurent. I read every review of the Paris collections!” Travis Smith, the model, spent his youngest years on Kaua‘i’s Päpa‘a Beach and then in Kïlauea, where he and his brothers were home-schooled by a pair of teachers named Mad Dog and Auntie Pam so they could spend their lives in the ocean; there Travis honed a physique that Donatella Versace dressed up and put in magazines around the world. And John Pfeiffer, the casting director, was born in Waikïkï and grew up between Honolulu and the Philippines. A self-described “clothes-obsessed kid,” he would drag his mother to Sears at Ala Moana and scope out three-piece matching outfits; in the Philippines he had his school uniform tailor, Mr. Moody, sew him bellbottoms with cuffs of outrageous proportions. “Wider, Mr. Moody,” he would urge. “Wider!”

I’m with John now. It’s late morning on day three of Fashion Week, and we’re backstage at the Prabal Gurung show. Prabal is a young, hip designer from Nepal whose eclectic roster of clients includes Oprah, Lady Gaga, the Duchess of Cambridge and Target. The show marks his third year at Fashion Week, and it couldn’t be more different from Parke & Ronen’s. It’s happening in a largely abandoned nineteenth-century building in Midtown, in a vast, dark space with a transparent cube in its midst. Imagine a fashion show as Stanley Kubrick might have devised it: Forty models stand inside the cube, all of them visible through its plastic surfaces, all of them wearing Prabal’s collection. They are a glorious mosaic of form, texture and color. A haunting, insistent score plays as one by one the girls—they are always called girls, never women—exit the cube, circumnavigate it and then re-enter to take their place once more. Of the eleven shows I’ll see this week, Prabal’s is easily the most interesting and creative.

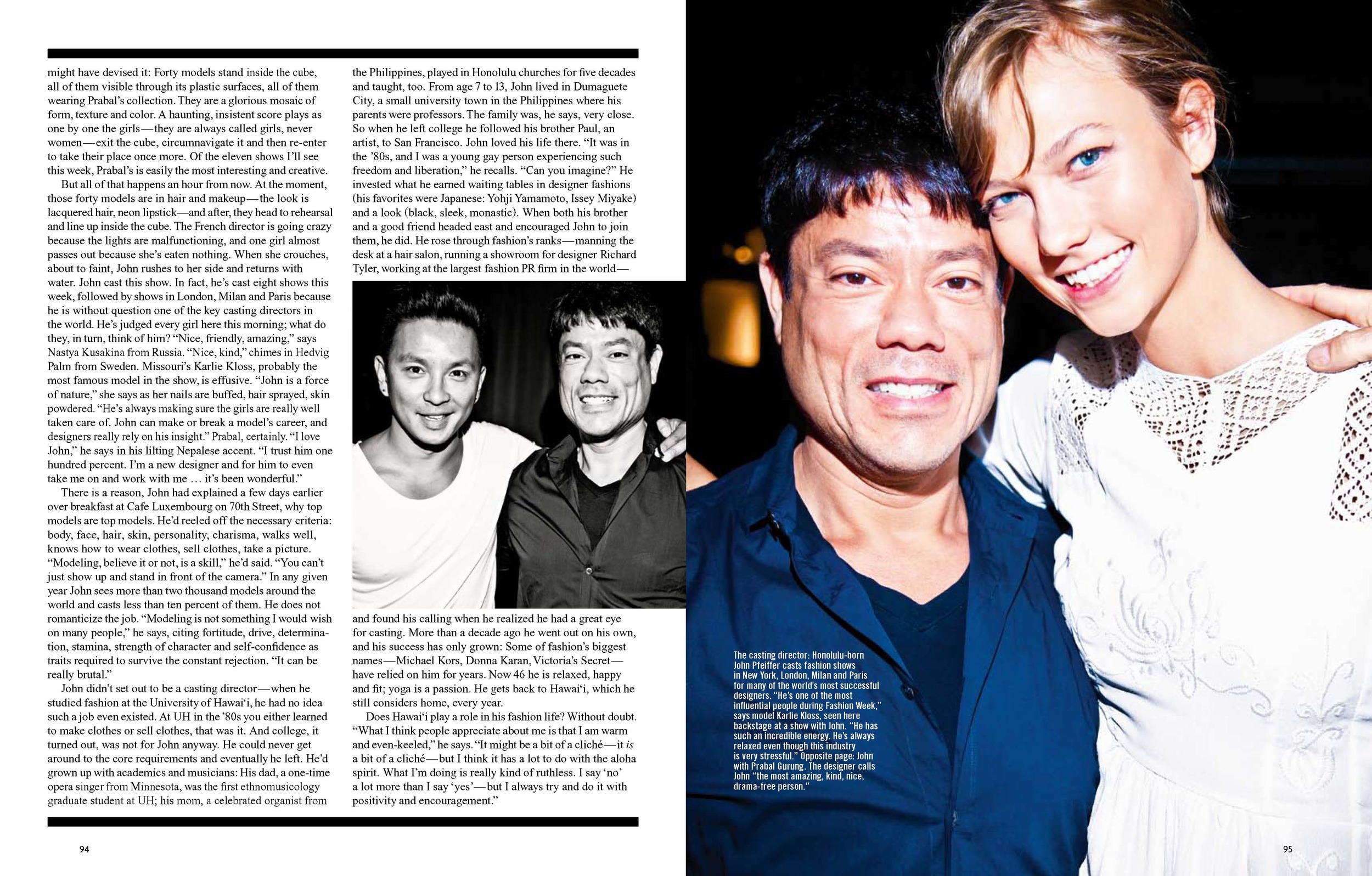

But all of that happens an hour from now. At the moment, those forty models are in hair and makeup—the look is lacquered hair, neon lipstick—and after, they head to rehearsal and line up inside the cube. The French director is going crazy because the lights are malfunctioning, and one girl almost passes out because she’s eaten nothing. When she crouches, about to faint, John rushes to her side and returns with water. John cast this show. In fact, he’s cast eight shows this week, followed by shows in London, Milan and Paris because he is without question one of the key casting directors in the world. He’s judged every girl here this morning; what do they, in turn, think of him? “Nice, friendly, amazing,” says Nastya Kusakina from Russia. “Nice, kind,” chimes in Hedvig Palm from Sweden. Missouri’s Karlie Kloss, probably the most famous model in the show, is effusive. “John is a force of nature,” she says as her nails are buffed, hair sprayed, skin powdered. “He’s always making sure the girls are really well taken care of. John can make or break a model’s career, and designers really rely on his insight.” Prabal, certainly. “I love John,” he says in his lilting Nepalese accent. “I trust him one hundred percent. I’m a new designer and for him to even take me on and work with me … it’s been wonderful.”

There is a reason, John had explained a few days earlier over breakfast at Cafe Luxembourg on 70th Street, why top models are top models. He’d reeled off the necessary criteria: body, face, hair, skin, personality, charisma, walks well, knows how to wear clothes, sell clothes, take a picture. “Modeling, believe it or not, is a skill,” he’d said. “You can’t just show up and stand in front of the camera.” In any given year John sees more than two thousand models around the world and casts less than ten percent of them. He does not romanticize the job. “Modeling is not something I would wish on many people,” he says, citing fortitude, drive, determination, stamina, strength of character and self-confidence as traits required to survive the constant rejection. “It can be really brutal.”

John didn’t set out to be a casting director—when he studied fashion at the University of Hawai‘i, he had no idea such a job even existed. At UH in the ’80s you either learned to make clothes or sell clothes, that was it. And college, it turned out, was not for John anyway. He could never get around to the core requirements and eventually he left. He’d grown up with academics and musicians: His dad, a one-time opera singer from Minnesota, was the first ethnomusicology graduate student at UH; his mom, a celebrated organist from the Philippines, played in Honolulu churches for five decades and taught, too. From age 7 to 13, John lived in Dumaguete City, a small university town in the Philippines where his parents were professors. The family was, he says, very close. So when he left college he followed his brother Paul, an artist, to San Francisco. John loved his life there. “It was in the ’80s, and I was a young gay person experiencing such freedom and liberation,” he recalls. “Can you imagine?” He invested what he earned waiting tables in designer fashions (his favorites were Japanese: Yohji Yamamoto, Issey Miyake) and a look (black, sleek, monastic). When both his brother and a good friend headed east and encouraged John to join them, he did. He rose through fashion’s ranks—manning the desk at a hair salon, running a showroom for designer Richard Tyler, working at the largest fashion PR firm in the world—and found his calling when he realized he had a great eye for casting. More than a decade ago he went out on his own, and his success has only grown: Some of fashion’s biggest names—Michael Kors, Donna Karan, Victoria’s Secret—have relied on him for years. Now 46 he is relaxed, happy and fit; yoga is a passion. He gets back to Hawai‘i, which he still considers home, every year.

Does Hawai‘i play a role in his fashion life? Without doubt. “What I think people appreciate about me is that I am warm and even-keeled,” he says. “It might be a bit of a cliché—it is a bit of a cliché—but I think it has a lot to do with the aloha spirit. What I’m doing is really kind of ruthless. I say ‘no’ a lot more than I say ‘yes’—but I always try and do it with positivity and encouragement.”

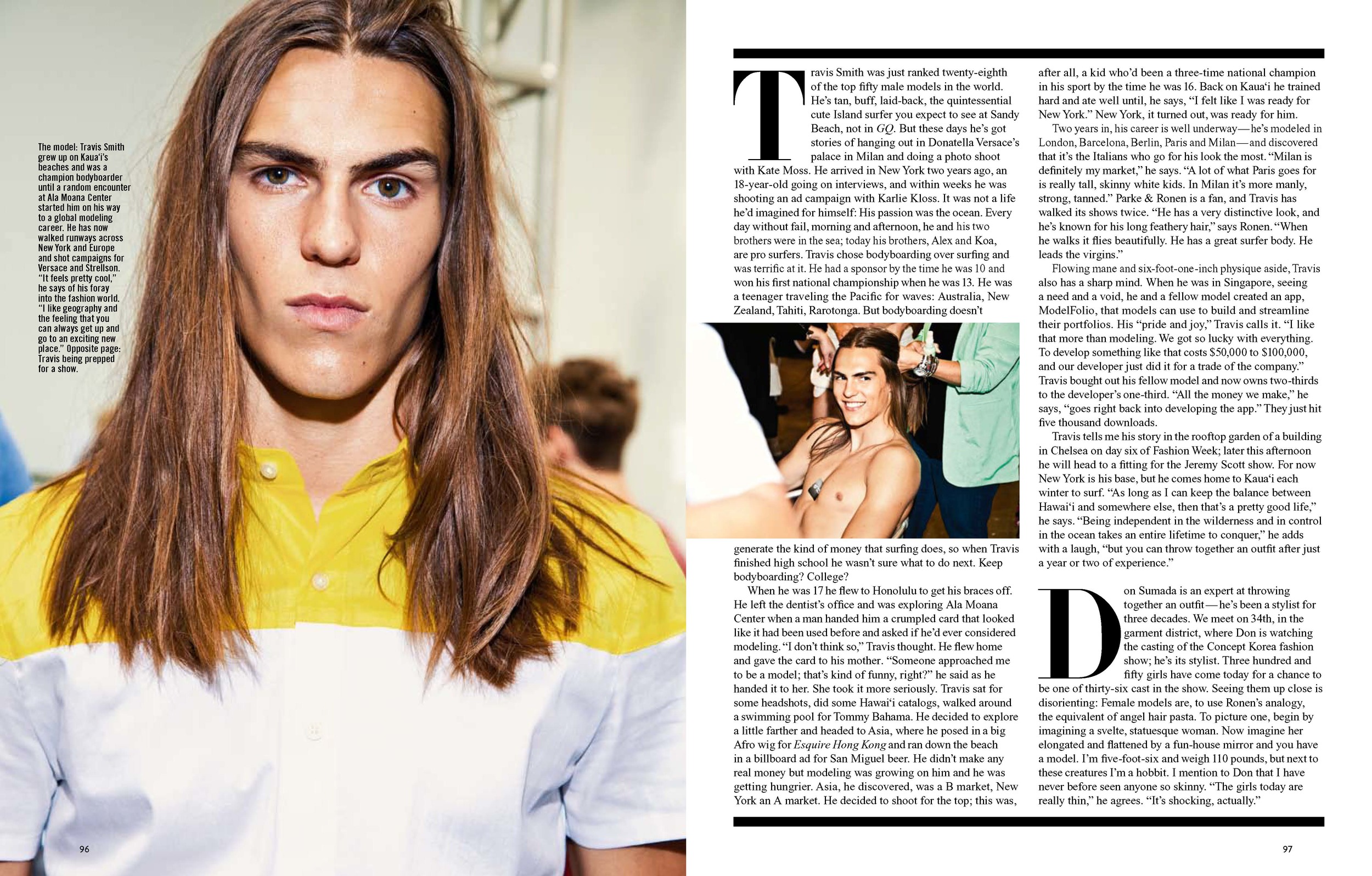

Travis Smith was just ranked twenty-eighth of the top fifty male models in the world. He’s tan, buff, laid-back, the quintessential cute Island surfer you’d see at Sandy Beach, not in GQ. But these days he’s got stories of hanging out in Donatella Versace’s palace in Milan and doing a photo shoot with Kate Moss. He arrived in New York two years ago, an 18-year-old going on interviews, and within weeks he was shooting an ad campaign with Karlie Kloss. It was not a life he’d imagined for himself: His passion was the ocean. Every day without fail, morning and afternoon, he and his two brothers were in the sea; today his brothers, Alex and Koa, are pro surfers. Travis chose body-boarding over surfing and was terrific at it. He had a sponsor by the time he was 10 and won his first national championship when he was 13. He was a teenager traveling the Pacific for waves: Australia, New Zealand, Tahiti, Rarotonga. But body-boarding doesn’t generate the kind of money that surfing does, so when Travis finished high school he wasn’t sure what to do next. Keep body-boarding? College?

When he was 17 he flew to Honolulu to get his braces off. He left the dentist’s office and was exploring Ala Moana Center when a man handed him a crumpled card that looked like it had been used before and asked if he’d ever considered modeling. “I don’t think so,” Travis thought. He flew home and gave the card to his mother. “Someone approached me to be a model; that’s kind of funny, right?” he said as he handed it to her. She took it a little more seriously. Travis sat for some headshots, did some Hawai‘i catalogs, walked around a swimming pool for Tommy Bahama. He decided to explore a little farther and headed to Asia, where he posed in a big Afro wig for Esquire Hong Kong and ran down the beach in a billboard ad for San Miguel beer. He didn’t make any real money but modeling was growing on him and he was getting hungrier. Asia, he discovered, was a B market, New York an A market. He decided to shoot for the top; this was, after all, a kid who’d been a three-time national champion in his sport by the time he was 16. Back on Kaua‘i he trained hard and ate well until, he says, “I felt like I was ready for New York.” New York, it turned out, was ready for him.

Two years in, his career is well underway—he’s modeled in London, Barcelona, Berlin, Paris and Milan—and discovered that it’s the Italians who go for his look the most. “Milan is definitely my market,” he says. “A lot of what Paris goes for is really tall, skinny white kids. In Milan it’s more manly, strong, tanned.” Parke & Ronen is a fan, and Travis has walked its shows twice. “He has a very distinctive look, and he’s known for his long feathery hair,” says Ronen. “When he walks it flies beautifully. He has a great surfer body. He leads the virgins.”

Flowing mane and six-foot-one-inch physique aside, Travis also has a sharp mind. When he was in Singapore, seeing a need and a void, he and a fellow model created an app, ModelFolio, that models can use to build and streamline their portfolios. His “pride and joy,” Travis calls it. “I like that more than modeling. We got so lucky with everything. To develop something like that costs $50,000 to $100,000, and our developer just did it for a trade of the company.” Travis bought out his fellow model and now owns two-thirds to the developer’s one-third. “All the money we make,” he says, “goes right back into developing the app.” They just hit five thousand downloads.

Travis tells me his story in the rooftop garden of a building in Chelsea on day six of Fashion Week; later this afternoon he will head to a fitting for the Jeremy Scott show. For now New York is his base, but he comes home to Kaua‘i each winter to surf. “As long as I can keep the balance between Hawai‘i and somewhere else, then that’s a pretty good life,” he says. “Being independent in the wilderness and in control in the ocean takes an entire lifetime to conquer,” he adds with a laugh, “but you can throw together an outfit after just a year or two of experience.”

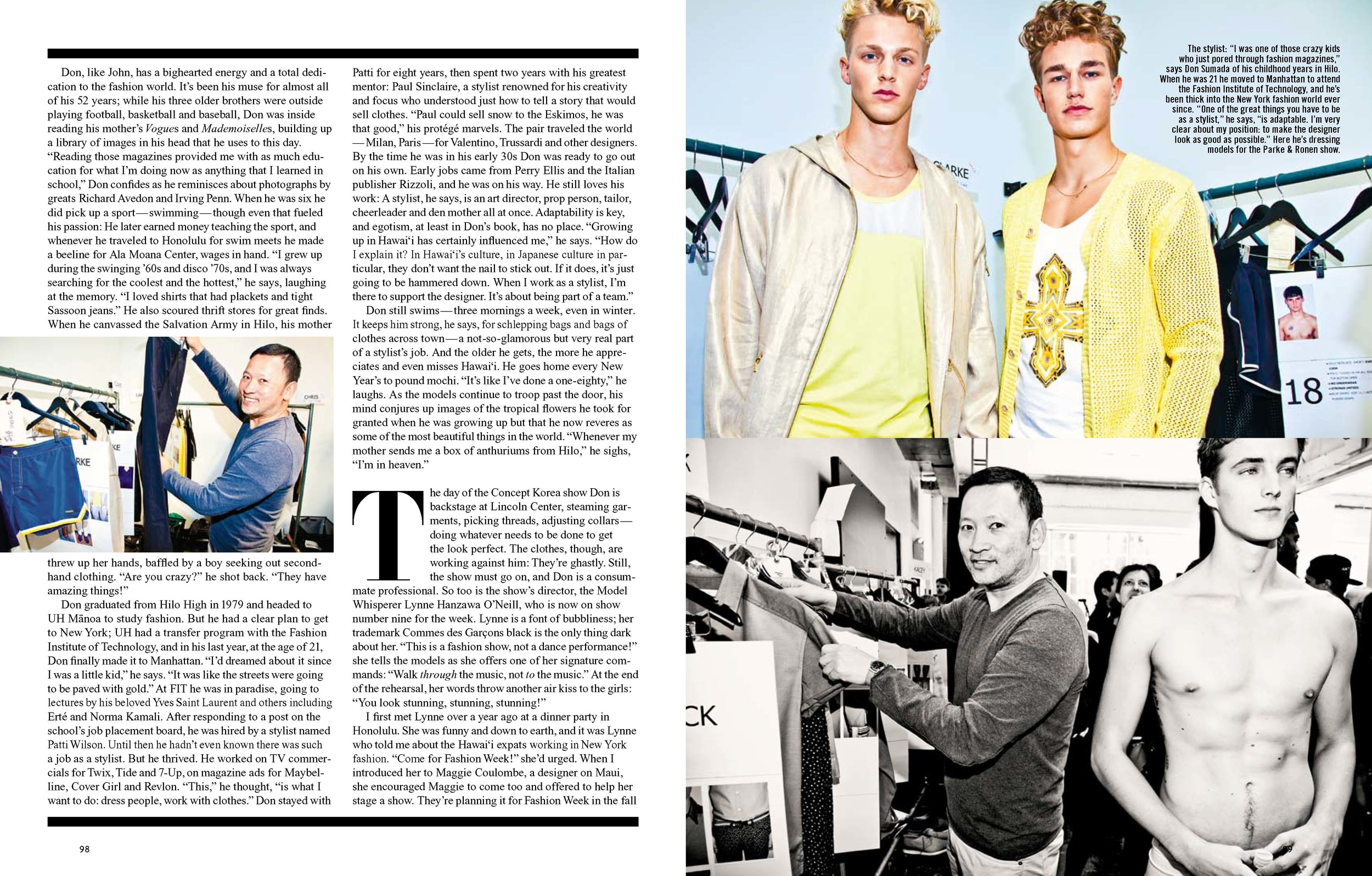

Don Sumada is an expert at throwing together an outfit—he’s been a stylist for three decades. We meet on 34th, in the garment district, where Don is watching the casting of the Concept Korea fashion show; he’s its stylist. Three hundred and fifty girls have come today for a chance to be among thirty-six cast. Seeing them up close is disorienting: Female models are, to use Ronen’s analogy, the equivalent of angel hair pasta. To picture one, begin by imagining a svelte, statuesque woman. Now imagine her elongated and flattened by a fun-house mirror and you have a model. I’m five-foot-six and weigh 110 pounds, but next to these creatures I’m a hobbit. I mention to Don that I have never seen anyone so skinny. “The girls today are really thin,” he agrees. “It’s shocking, actually.”

Don, like John, has a bighearted energy and a total dedication to the fashion world. It’s been his muse for almost all of his 52 years; while his three older brothers were outside playing football, basketball and baseball, Don was inside reading his mother’s Vogues and Mademoiselles, building up a library of images in his head that he uses to this day. “Reading those magazines provided me with as much education for what I’m doing now as anything that I learned in school,” Don confides as he reminisces about photographs by greats Richard Avedon and Irving Penn. When he was six he did pick up a sport—swimming—though even that fueled his passion: He later earned money teaching the sport, and whenever he traveled to Honolulu for swim meets he made a beeline for Ala Moana Center, wages in hand. “I grew up during the swinging ’60s and disco ’70s, and I was always searching for the coolest and the hottest,” he says, laughing at the memory. “I loved shirts that had plackets and tight Sassoon jeans.” He also scoured thrift stores for great finds. When he canvassed the Salvation Army in Hilo, his mother threw up her hands, baffled by a boy seeking out second-hand clothing. “Are you crazy?” he shot back. “They have amazing things!”

Don graduated from Hilo High in 1979 and headed to UH Mänoa to study fashion. But he had a clear plan to get to New York; UH had a transfer program with the Fashion Institute of Technology, and in his last year, at the age of 21, Don finally made it to Manhattan. “I’d dreamed about it since I was a little kid,” he says. “It was like the streets were going to be paved with gold.” At FIT he was in paradise, going to lectures by his beloved Yves Saint Laurent and others including Erté and Norma Kamali. After responding to a post on the school’s job placement board, he was hired by a stylist named Patti Wilson. Until then he hadn’t even known there was such a job as a stylist. But he thrived. He worked on TV commercials for Twix, Tide and 7-Up, on magazine ads for Maybelline, Cover Girl and Revlon. “This,” he thought, “is what I want to do: dress people, work with clothes.” Don stayed with Patti for eight years, then spent two years with his greatest mentor: Paul Sinclaire, a stylist renowned for his creativity and focus who understood just how to tell a story that would sell clothes. “Paul could sell snow to the Eskimos, he was that good,” his protégé marvels. The pair traveled the world—Milan, Paris—for Valentino, Trussardi and other designers. By the time he was in is early 30s Don was ready to go out on his own. Early jobs came from Perry Ellis and the Italian publisher Rizzoli, and he was on his way. He still loves his work: A stylist, he says, is an art director, prop person, tailor, cheerleader and den mother all at once. Adaptability is key, and egotism, at least in Don’s book, has no place. “Growing up in Hawai‘i has certainly influenced me,” he says. “How do I explain it? In Hawai‘i’s culture, in Japanese culture in particular, they don’t want the nail to stick out. If it does, it’s just going to be hammered down. When I work as a stylist, I’m there to support the designer. It’s about being part of a team.”

Don still swims—three mornings a week, even in winter. It keeps him strong, he says, for schlepping bags and bags of clothes across town—a not-so-glamorous but very real part of a stylist’s job. And the older he gets, the more he appreciates and even misses Hawai‘i. He goes home every New Year’s to pound mochi. “It’s like I’ve done a one-eighty,” he laughs. As the models continue to troop past the door, his mind conjures up images of the tropical flowers he took for granted when he was growing up but that he now reveres as some of the most beautiful things in the world. “Whenever my mother sends me a box of anthuriums from Hilo,” he sighs, “I’m in heaven.”

The day of the Concept Korea show Don is backstage at Lincoln Center, steaming garments, picking threads, adjusting collars—doing whatever needs to be done to get the look perfect. The clothes, though, are working against him: They’re ghastly. Still, the show must go on, and Don is a consummate professional. So too is the show’s director, the Model Whisperer Lynne O’Neill, who is now on show number nine for the week. Lynne is a font of bubbliness; her trademark Commes des Garçons black is the only thing dark about her. “This a fashion show, not a dance performance!” she tells the models as she offers one of her signature commands: “Walk through the music, not to the music.” At the end of the rehearsal, her words throw another air kiss to the girls: “You look stunning, stunning, stunning!”

I first met Lynne over a year ago at a dinner party in Honolulu. She was funny and charming and down to earth, and it was Lynne who told me about Don and John and Travis and others from Hawai‘i working in New York fashion. “Come for Fashion Week!” she’d urged. When I introduced her to Maggie Coulombe, a designer on Maui, she encouraged Maggie to come too and offered to help her stage a show. They’re planning it for Fashion Week 2014; this year Maggie provided the entire wardrobe I’ve been wearing in Manhattan: ultra-chic skirts, shirts and dresses.

When Margaret Cho played Lynne on Sex and the City, she constantly dropped the F-bomb, but the real Lynne is far more decorous. Stylist Deborah Watson put her arm around Lynne at one point during Fashion Week and called her “a ray of Hawaiian sunshine, one hundred percent aloha twenty-four/seven.” Lynne rolled her eyes, blushing, but everyone in the room agreed. Over the years Lynne has worked with countless designers as well as rock stars (including Mick and Keith) and chefs (including Julia, who gave Lynne a chicken she’d prepared for a cooking demo. “Delicious,” says Lynne. “I’ll never forget that”). She has been planning and staging events for decades, but—classic irony—of her own life she says, “I never tried to figure it out, I just trusted it was going to work.” She has always loved Hawai‘i, and even after her parents moved the family to Los Angeles she returned every summer to be with her grandparents; she even participated in the quintessential 1960s O‘ahu rite of passage: working at the Dole Cannery back when it was still a pineapple cannery. After high school she took her earnings and hitchhiked around Europe for three months; that, combined with the influence of a passionate teacher at West Los Angeles City College called Mr. Hilton, was enough to make her fall in love with art. She transferred to UCLA, where she pored through rare books by Leonardo da Vinci, and majored in art history with a focus on the Italian Renaissance. “I think,” she says, “I was Italian in a prior life.”

Newly graduated, newly married and 24, she moved north to San Francisco. She started volunteering at the museums in Golden Gate Park and in no time was helping to run the volunteer program, for Lynne is so confident and so competent that she is always being asked to take things on. But her time at the museums was cut short when her boss suggested she apply for a temp job doing special events for Macy’s. Lynne went to the interview: It lasted four hours, and the six-month job turned into five years. “Combat training,” Lynne calls her time at Macy’s. She was plunged into the world of events and promotions, and she loved it. It was the ’80s; the budgets were large and everybody showed up to hawk stuff: Gianni Versace, Calvin Klein, Perry Ellis, Jane Fonda, James Beard and even, to make chicken, Julia Child. “The biggest of the big,” recalls Lynne. “They say that Macy’s was the Harvard of retailing then. I had an incredible education.” After five years she’d had enough. She quit and moved to Japan to get in touch with her roots: time, she says, to be quiet, think and see. After six months she was ready to go back to SF and be a housewife. But that didn’t happen. Once she got home, friends she’d made at Macy’s kept calling her to help them stage events, and she started traveling the country working in places like Minneapolis and Detroit. In 1990 she got an apartment in New York and never looked back. “It all happened because I really didn’t want to do it,” she says of her career. “That’s kind of how it works for me.” She and her second husband, Bobby O’Neill, now divide their time among Manhattan, upstate New York and Hawai‘i. “I call what Lynne does ‘aloha Zen,’” Bobby shouts in my ear at the Todd Oldham show; the techno music is blasting and we’re watching Lynne in her element, getting the boys ready to go onstage. “When you get Lynne, you get the friendliness of aloha and the Zen calm of a samurai.

My last day of Fashion Week I head to the Michael Kors show at Lincoln Center, another cast by John. Backstage more models sing his praises. “Very lovely,” says Czechoslovakia’s Karolina Kurkova. “One of the nicest people I know,” adds France’s Anais Mali. The compliments are endless. And when the lights come on, the music starts and the show’s fifty-three models walk the runway, the looks are beautiful: light, flowing, summery.

In the afternoon I leave the fashion world far, far behind me and take the subway down to the Village to have tea with a friend, Oliver Sacks, a neurologist famous for his endless curiosity and wonderful writings. Oliver is a man of science and big ideas, and within minutes of my arrival at his apartment we are talking about the brains of marine invertebrates. We’re discussing jellyfish, not clothing, yet before I go, I can’t help but ask Oliver, who understands so much about the brain: What is it that draws us to fashion? He gamely gives me an answer, one informed by biology and evolution. Regardless of species, he says, ultimately the draw to color, to form, to beauty is all about sexual selection and the quest to be distinctive enough to be noticed, desired and chosen. Our markings—be they innate or bought off the rack—might not be practical but they have definite purpose. “Take, for example, the peacock’s tail,” Oliver says, choosing one of the most outrageous examples of couture in the animal kingdom. “It’s completely maladaptive—but the ladies seem to like it.”