This is a story about palms, but for me it starts here: on the dance floor of a Honolulu nightclub called Anna Bannanas. To give you an idea of how far back we’re going: The band is playing Free Nelson Mandela. To give you an idea of why we’re here: Out on the floor, there’s a Chinese guy gyrating wildly. He’s twisting and bopping and whirling, and he’s three sheets to the wind. When the band finally breaks, he comes over and hurls himself into a chair. “Well,” he says, with a droll laugh and a voice that recalls a young Laurence Olivier, “wasn’t that special?” Then he leans over and introduces himself: Alan Young, enchanté.

Two decades later he’s a good friend, this bon vivant, global nomad, foodie extraordinaire. To picture Alan, think Oscar Wilde (cultured, caustic), then Julia Child (brilliant cook), then fuse them. The Wilde Child you’ve concocted is Alan. These days he lives in Hilo, in a little house on Kino‘ole Street, where he whips up dishes to sell at farmers’ markets in East Hawai‘i. Whenever I get off the plane in Hilo now, I make a beeline for his house and raid his fridge. Maybe I’ll find perfectly spiced lentils or a minty Moroccan salad or Peruvian gold potatoes. My favorite of his dishes is a dessert: the liliko‘i tapioca. It’s worth the price of the flight.

While I eat, Alan fills me in on his life. Always he has travels and recipes to talk of and news to share—and it was during one of those conversations that he told me he’d become president of the Hawai‘i Island Palm Society.

“Jeez,” I said, “I didn’t realize you were that involved with palms.”

“I’m not,” came the retort. “But I’d just gotten off a flight from India, and I was sitting at my kitchen table, and I’d had quite a bit of wine to drink, and Karen Piercy called and ambushed me, and the next thing I knew I was the president.”

A reverse coup—thrust into power in a moment of weakness.

“So are you growing palms then?” I queried. I was being seduced by a palm as I asked, eating my second bowl of tapioca and marveling at the fullness of its coconut flavor.

This time the voice was pure Vincent Price. “Honey, I killed the only palm I ever owned. They just wanted a pretty face.”

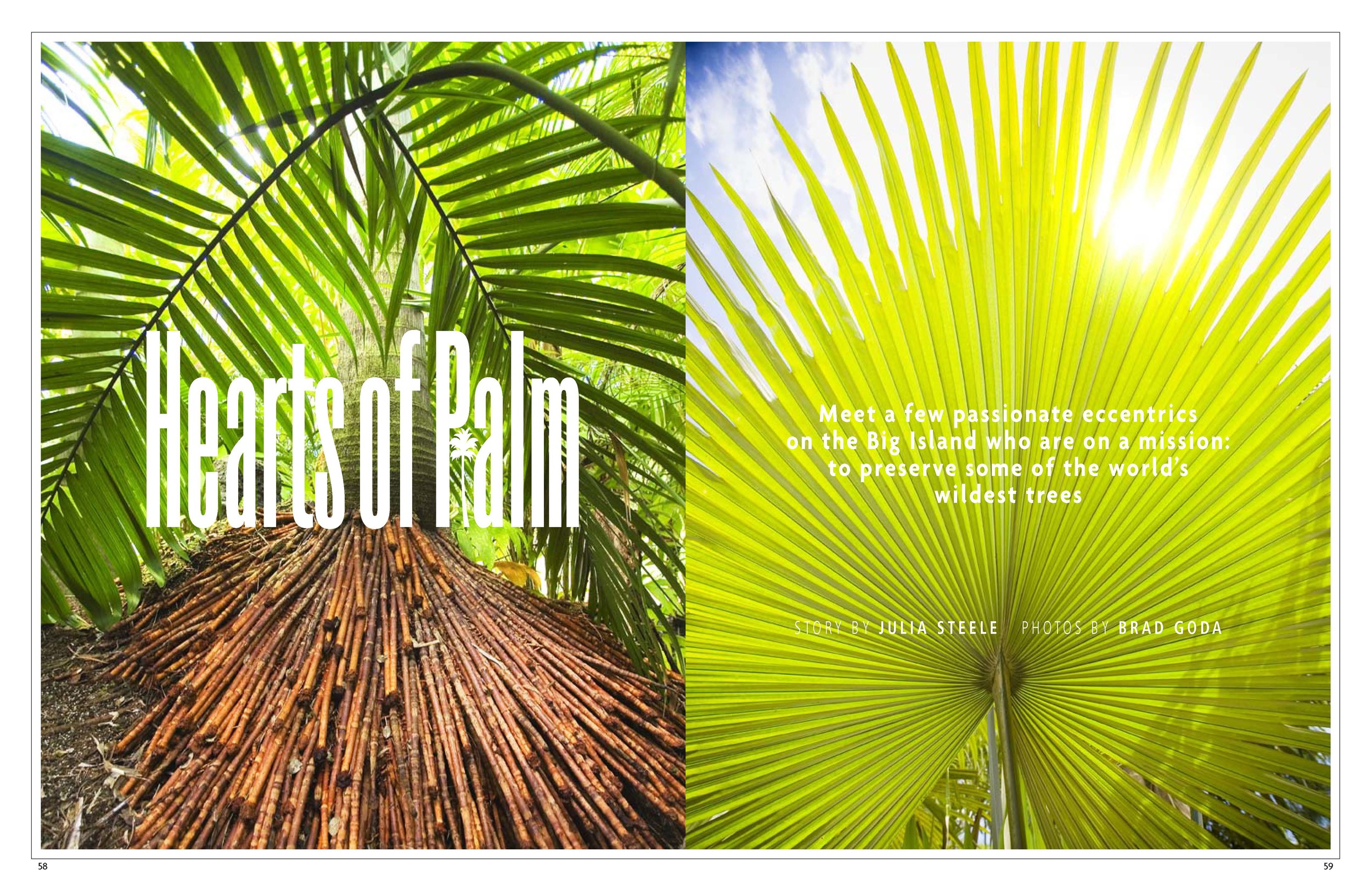

Palms are fantastic creatures. They are statuesque, graceful and generous. They’re self-reliant and self-controlled. They’re the ultimate marker of the most bewitching place on earth: the tropics. Back in Honolulu, I kept thinking about the Hawai‘i Island Palm Society. Who, I wondered, were these people who’d appointed Alan their leader? I called my friend Jan to ask what she knew about palm-ophiles in the Islands. Jan’s a hard-core botanist, one of those people who can tell you—in Latin—the name of every plant in your yard, one of those people who will fly halfway around the world to see some exotic flower put on a cabaret.

Jan didn’t know anything specific about the palm society (HIPS for short), but she had some more general ideas. “Palm people,” she said, “are weird. They’re always sneaking around with flashlights looking to get seeds off your trees. They’re a bizarre group, they really are.”

I rattled off a half-formed theory that there was something interesting somewhere between the complex botany of palms and the wacky sociology of the Big Island, but Jan didn’t seem to have heard.

“They’re a kinky crowd,” she said just before she hung up.

I called Alan. He was in the middle of making pasta salad with fennel and dal baht with rajma. “What can I say?” he said. “I’m just a little cooking devil.”

“Alan,” I said, “can you tell me more about the palm society?”

There was silence on the other end of the line while he thought. “Well, it attracts idiosyncratic intelligent retired folks,” he said. “In my tenure, I tried to give it a strong local face. Did it work? Sort of. But it’s not like the Ikebana Society at the Hongwanji, dear. You know, East is East and West is West and what-ev-er. There are so many garden societies here: orchids, rhododendrons, et cetera, et cetera. It’s the Big Island!” The big, lush, verdant and fertile island.

When Alan called back to say that one of the world’s foremost palm experts was heading to Hilo to speak to the HIPS crowd, I knew my chance to learn more had come. I hopped a plane, got a car and headed for an agricultural extension office up in the hills of town.

The expert was Don Hodel. His audience of forty or so HIPSters sat spellbound for an hour as he talked about Clinostigma samoensis and Howeia forsteriana. They asked questions about germination, inflorescences, rates of growth. These people might have once installed Alan as their president, I realized, but they weren’t kidding around when it came to palms (and anyway, installing Alan as their president was a crazy-like-a-fox move: Who do you think brought food to the meetings?).

Restacking chairs after Hodel finished, I introduced myself to some of the HIPSters. I met Karel, a Czech dissident who used to collect crocodiles in Prague; Jan, a Canadian self-described “child of the ’60s” whose son learned to say Chrysalidocarpus lutescens at the age of two; Bo, a fastidious Swede who’s planted—by himself—5,000 palms around his home at last count; and Jeff, a belligerent eccentric who, it turned out, had been waiting for me. “You work for that in-flight magazine? I’ve been meaning to call you to come out and do a story on me. I’ve got things to say that need to be heard.” He gave me a number to reach him. Everyone gave me a number.

Walking to my car, I felt the cheery zeal that always comes when I’m on the cusp of discovery. Months later, as I reach the end of this story, that cheery zeal has changed to stanch appreciation—for now I know what a truly quirky, enchanting and significant tale I stumbled on as I sat eating in Alan’s kitchen.

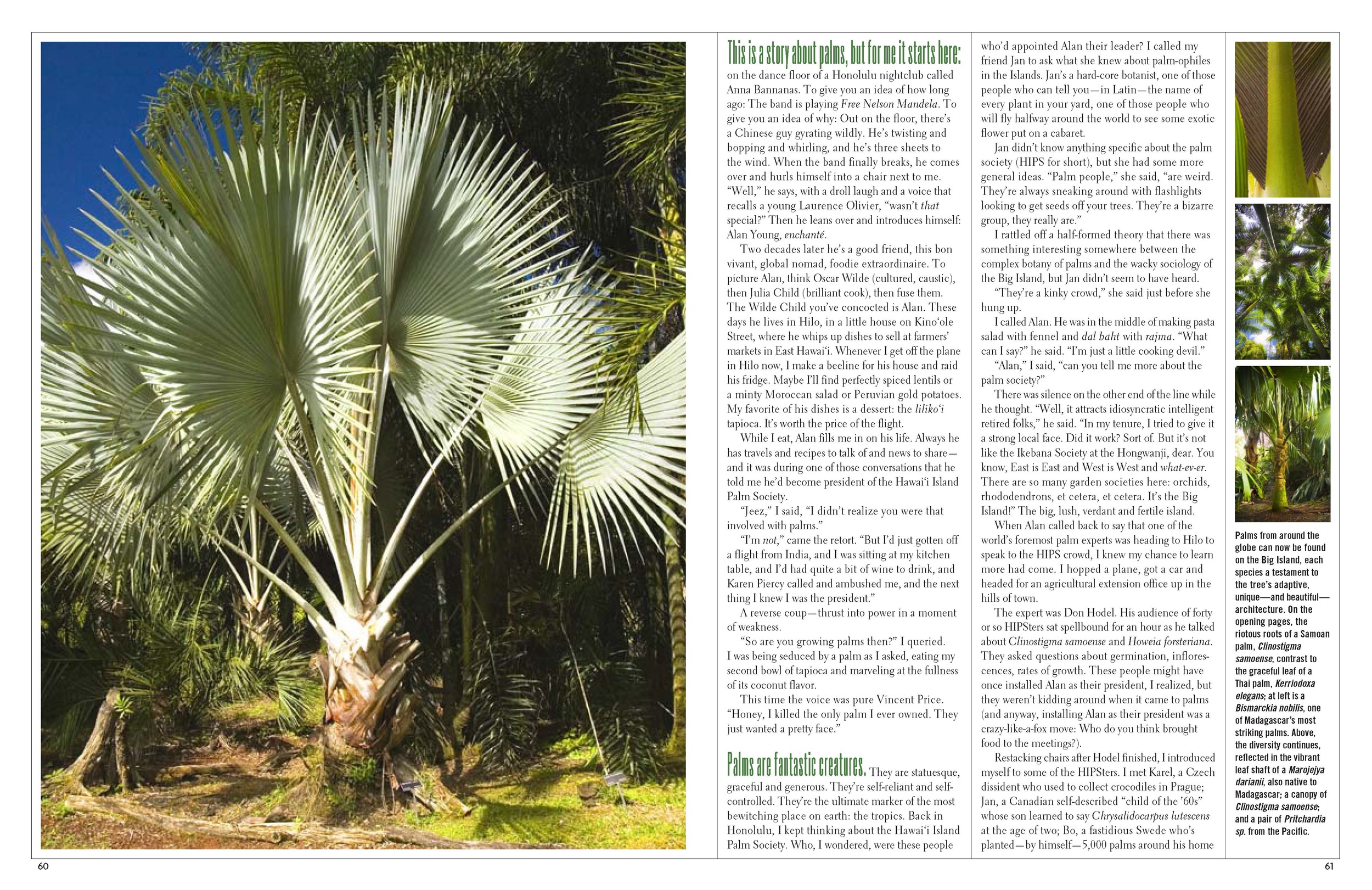

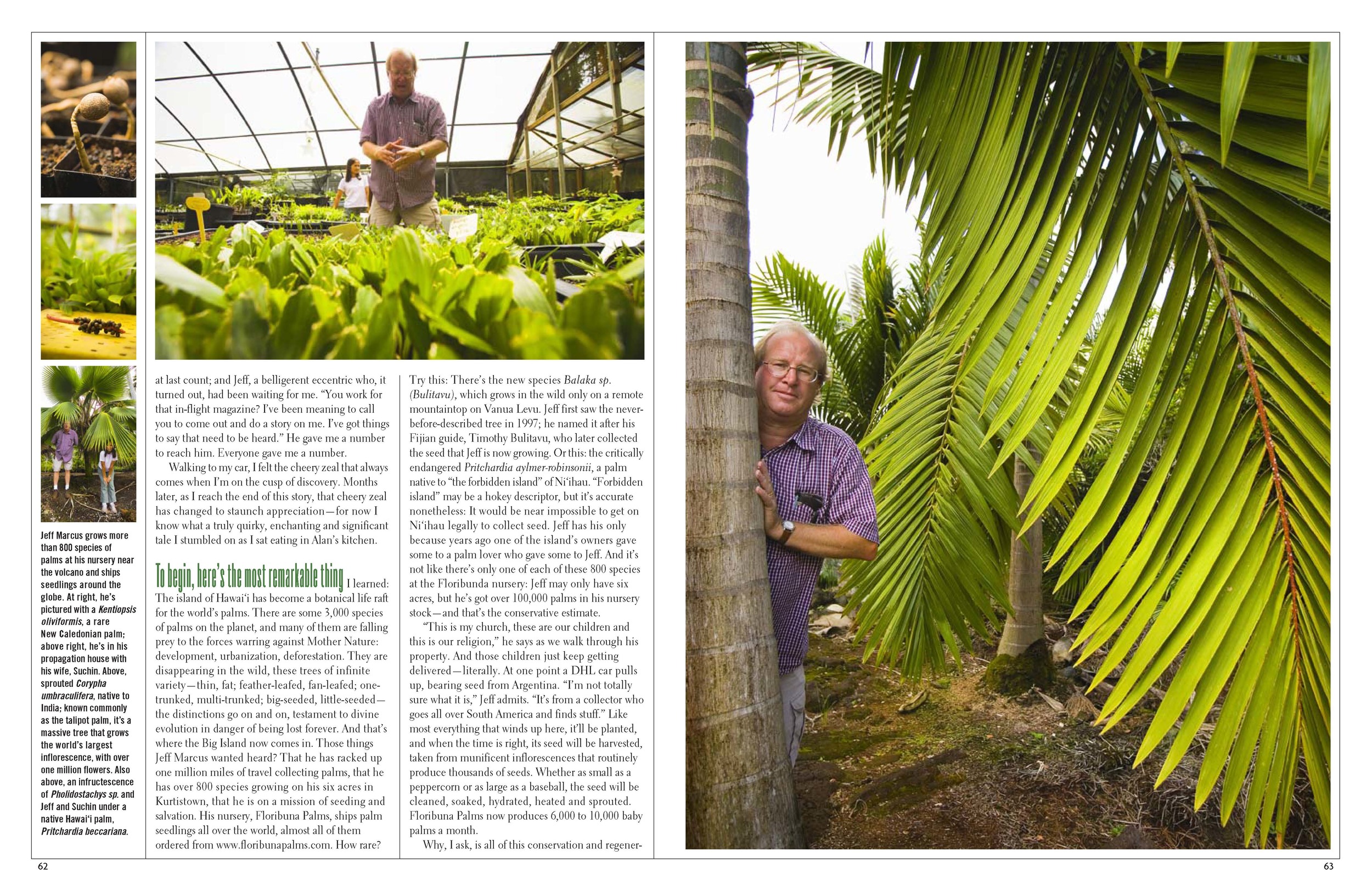

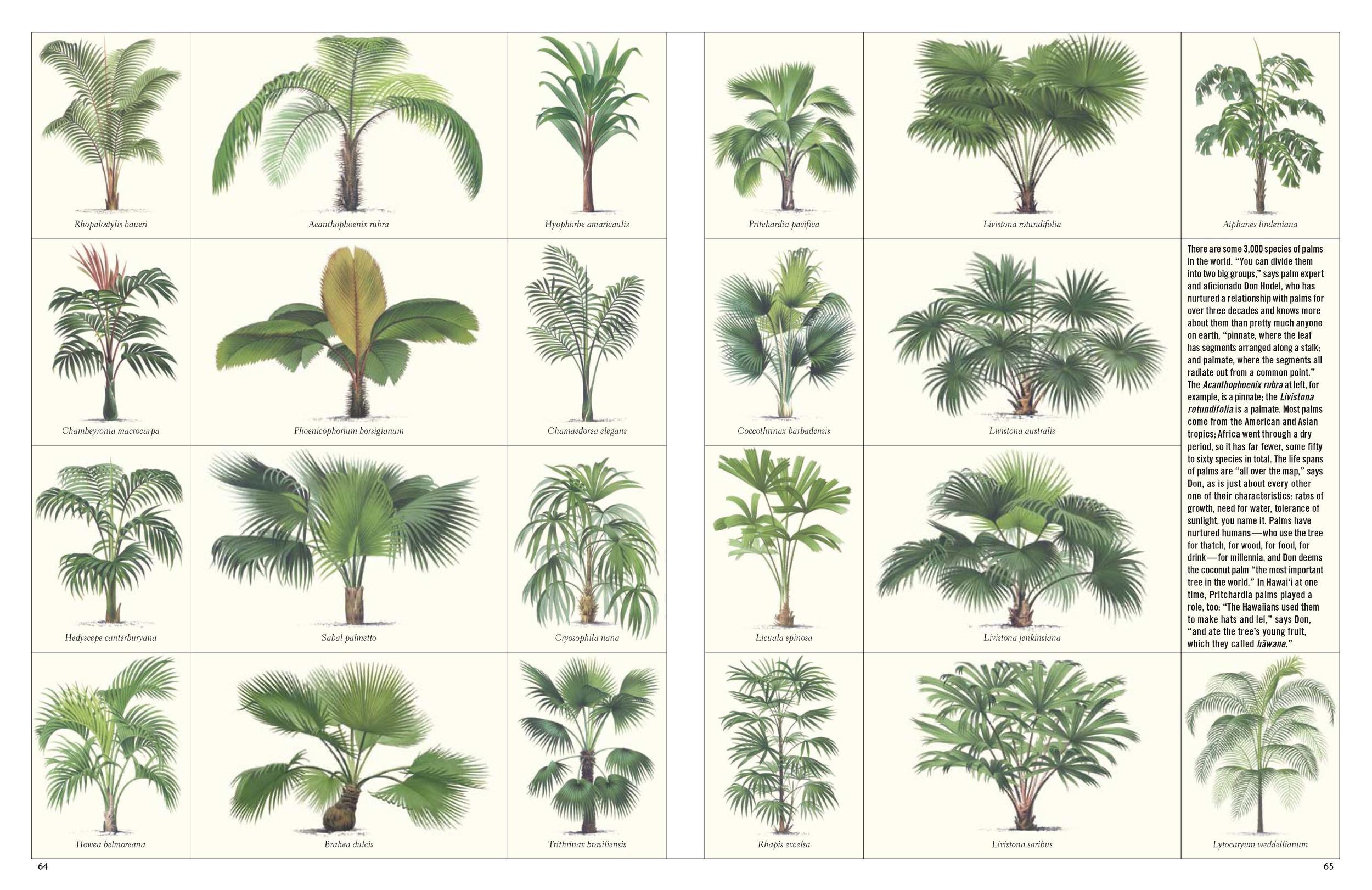

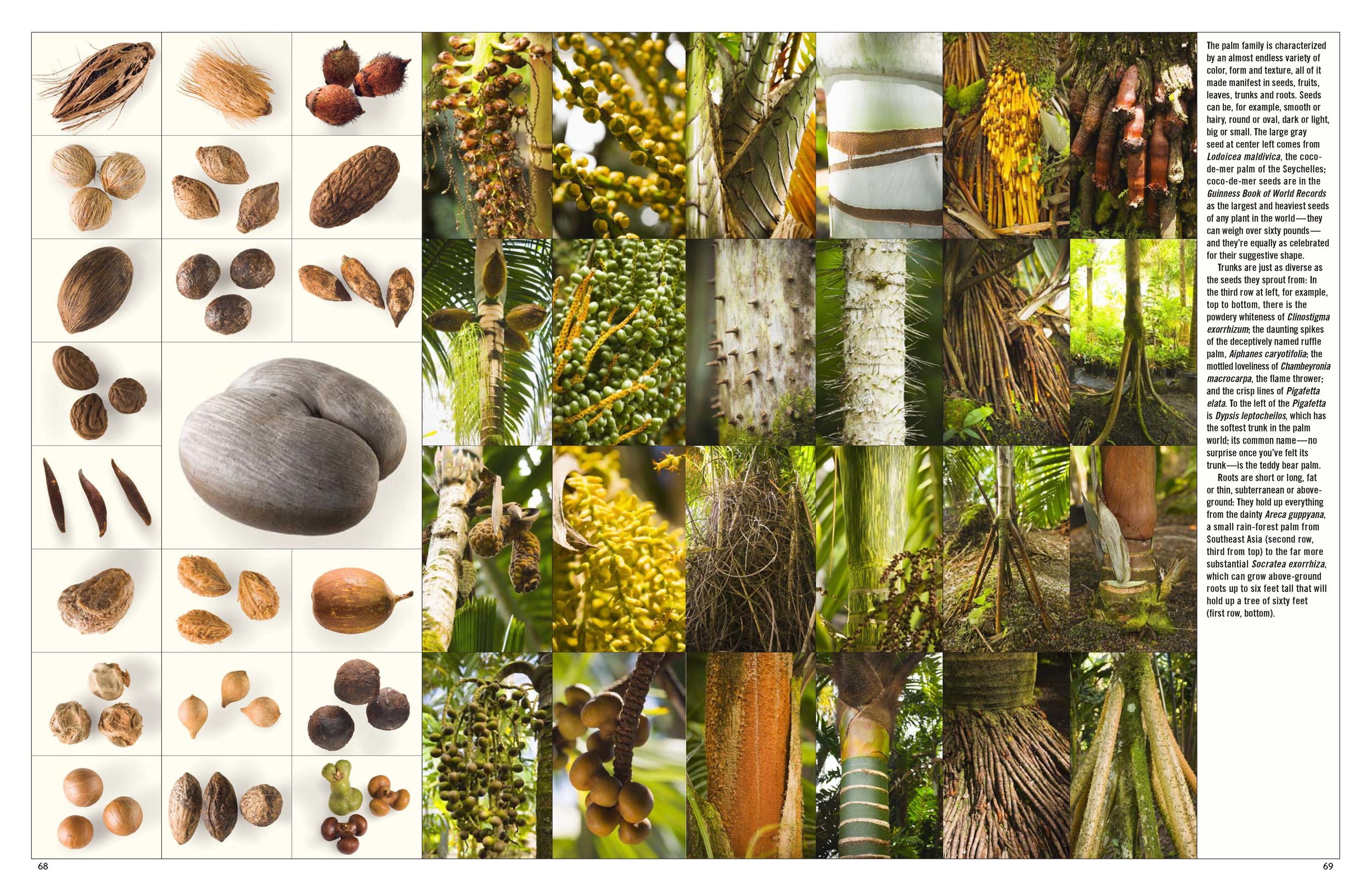

To begin, here’s the most remarkable thing I learned: The island of Hawai‘i has become a botanical life raft for the world’s palms. There are some 3,000 species of palms on the planet, and many of them are falling prey to the forces warring against Mother Nature: development, urbanization, deforestation. They are disappearing in the wild, these trees of infinite variety—thin, fat; feather-leafed, fan-leafed; one-trunked, multi-trunked; big-seeded, little-seeded—the distinctions go on and on, testament to divine evolution in danger of being lost forever. And that’s where the Big Island now comes in. Those things Jeff Marcus wanted heard? That he has racked up one million miles of travel collecting palms, that he has over 800 species growing on his six acres in Kurtistown, that he is on a mission of seeding and salvation. His nursery, Floribunda Palms, ships palm seedlings all over the world, almost all of them ordered from www.floribundapalms.com. How rare? Try this: there’s the new species Balaka sp. (Bulitavu), which grows in the wild only on a remote mountaintop on Vanua Levu. Jeff first saw the never-before-described tree in 1997; he named it after his Fijian guide, Timothy Bulitavu, who later collected the seed that Jeff is now growing. Or this: the critically endangered Pritchardia aylmer-robinsonii, a palm native to “the forbidden island” of Ni‘ihau. “Forbidden island” may be a hokey descriptor but it’s accurate nonetheless: It would be near impossible to get on Ni‘ihau legally to collect seed. Jeff has his only because years ago one of the island’s owners gave some to a palm lover who gave some to Jeff. And it’s not like there’s only one of each of these 800 species at the Floribunda nursery: Jeff may only have six acres, but he’s got over 100,000 palms in his nursery stock—and that’s the conservative estimate.

“This is my church, these are our children, and this is our religion,” he says as we walk through his property. And those children just keep getting delivered—literally. At one point, a DHL car pulls up, bearing seed from Argentina. “I’m not totally sure what it is,” Jeff admits. “It’s from a collector who goes all over South America and finds stuff.” Like most everything that winds up here, it’ll be planted, and when the time is right, its seed will be harvested, taken from munificent inflorescences that routinely produce thousands of seeds. Whether as small as a peppercorn or as large as a baseball, the seed will be cleaned, soaked, hydrated, heated and sprouted. Floribunda Palms now produces 6,000 to 10,000 baby palms a month.

Why, I ask, is all of this conservation and regeneration happening on the Big Island of all places? Turns out its climate is near-perfect for palms. “They love water, and they love good drainage,” Jeff explains. Hawai‘i Island, with its porous rock and abundance of rain, is just what the botanist ordered. And so Jeff is thriving. His obsession is diversity, and he’s hell-bent on getting growers to try new things. “I see the same seven basic palms everywhere,” he says, “ and it makes me want to gag.” At his nursery, he shows me hundreds of species I’ve never heard of, let alone seen before, fantastic trees including an “old man palm” from Cuba, so named because it grows a hairy beard; a dainty little cluster palm from the Philippines with bright purple crown shafts; and a palm from Madagascar that grows a unique leaf with a little window right in the middle. Jeff’s seedling list runs four pages of densely packed eight-point type, and there’s no doubt that he’s the most fanatical HIPSter there is; everyone I talked to agreed on that point. Jeff’s own take? “The difference between me and everyone else is that I’ve taken the time to go out into the bush and get leeches in my eyes.”

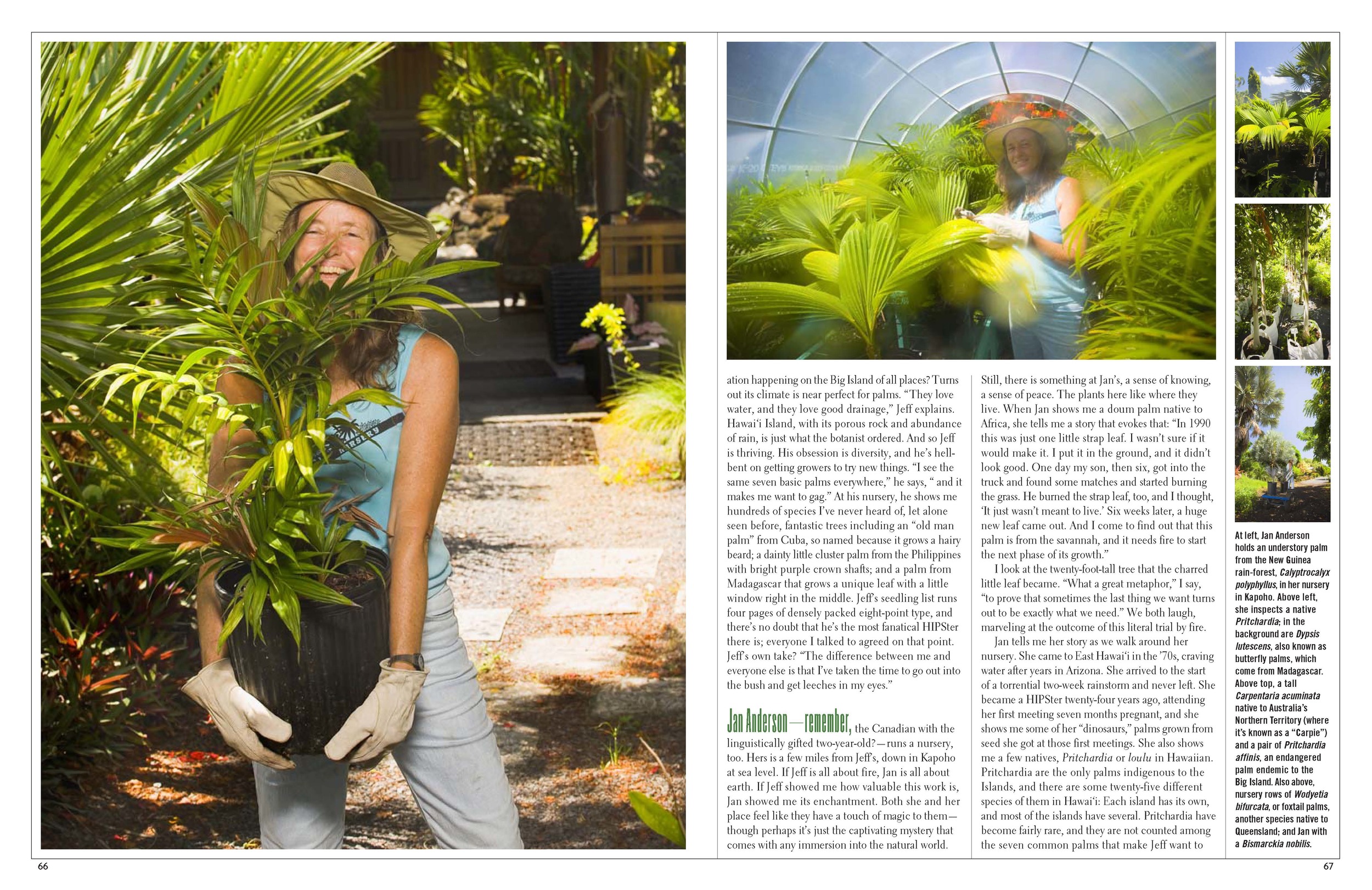

Jan Anderson—remember, the Canadian with the linguistically gifted two-year-old?—runs a nursery, too. Her’s is a few miles from Jeff’s, down in Kapoho at sea level. If Jeff is all about fire, Jan is all about earth. If Jeff showed me how valuable this work is, Jan showed me its enchantment. Both she and her place feel like they have a touch of magic to them—though perhaps it’s just the captivating mystery that comes with any immersion into the natural world. Still, there is something at Jan’s, a sense of knowing, a sense of peace. The plants here like where they live. When Jan shows me a doum palm native to Africa, she tells me a story that evokes that: “In 1990, this was just one little strap leaf. I wasn’t sure if it would make it. I put it in the ground, and it didn’t look good. One day my son, then six, got into the truck and found some matches and started burning the grass. He burned the strap leaf, too, and I thought, ‘It just wasn’t meant to live.’ Six weeks later, a huge new leaf came out. And I come to find out that this palm is from the savannah, and it needs fire to start the next phase of its growth.”

I look at the twenty-foot tall tree that the charred little leaf became. “What a great metaphor,” I say, “to prove that sometimes the last thing we want turns out to be exactly what we need.” We both laugh, marveling at the outcome of this literal trial-by-fire.

Jan tells me her story as we walk around her nursery. She came to East Hawai‘i in the ’70s, craving water after years in Arizona. She arrived to the start of a torrential two-week rainstorm and never left. She became a HIPSter twenty-four years ago, attending her first meeting seven months pregnant, and she shows me some of her “dinosaurs,” palms grown from seed she got at those first meetings. She also shows me a few natives, Pritchardia or loulu in Hawaiian. Pritchardia are the only palms indigenous to the Islands, and there are some twenty-five different species of them in Hawai‘i: Each island has its own, and most of the islands have several. Pritchardia have become fairly rare, and they are not counted among the seven common palms that make Jeff want to gag. Bringing them back—into the consciousness, into the landscape—is another mandate of the HIPS crowd.

Pritchardia aside, Jan says when it comes to palms she thinks in terms of beauty and landscape more than rarity and commonness. She points to a cluster of short trees with bright green fan-shaped leaves. “This is the first palm I ever fell in love with,” she tells me. “They’re Johannesteijsmannia altifrons, native to Malaysia. I saw a picture of the leaves used as thatch and thought, ‘Wow!’” Another, Licuala grandis, she “first fell in love with in a pot in a café in Indonesia. It looked so powerful and exotic.”

Listening to Jan talk about these palms she loves, I’m reminded of something Alan said: “Palms are not touchy feely—I mean, when you’ve got a tree that’s 100 feet tall outfitted in silver blue: naaaahhhh. Palms are like dinosaurs: sort of spectacular, way different, mysterious. You don’t get immediate gratification. You have to commit to the plant, establish a relationship.” Something about the certainty in his inflection made him sound just like Marlin Perkins from Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom.

If Jeff illustrates the significance of what’s happening on the Big Island and Jan the enchantment, Bo-Goran Lundkvist and Karel Havlicek offer a glimpse into the quirkiness. They are both collectors, both obsessive about plants. Karel, for example, has some 10,000 species on his three acres above Hilo. That’s 10,000 species, not 10,000 plants. Both are HIPSters, both immigrants from Europe who spent years in Southern California before striking out for the Big Island. There the similarity ends. Bo is all about order, symmetry. He is from Sweden, and he reminds me so much of Max von Sydow that I keep waiting for his placid exterior to give way to addled angst the way it always did in the movies. But it never happens: Bo is happy here with his palms. His garden, set on five acres in Leilani Estates, is an astonishing feat: 5,000 palms, 600 species, all laid out according to land of origin and meticulously labeled. Though technically it’s just Bo’s front yard, it feels more like a legit botanical garden than any other place I saw on the Big Island—and that includes a legit botanical garden.

If Bo’s place is like a painting by Mondrian, Karel’s place is a Pollock. It is a carnival, a wild celebration of color, texture, shape. Like Jeff, like Jan, like Bo, Karel talks of his plants with the affection, concern and pride of a parent. But he doesn’t grow only palms. He also shows me what he calls the biggest bromeliad I will ever see, a massive, mottled, rare creature called Vriesea hieroglyphica; one of the rarest philodendrons in the world, Philodendron spiritus-sancti; and the largest-growing cycad on earth, Encephalartos laurentianus. “How about this one?” he says pointing to a vibrant plant. “It was just discovered last year in Ecuador.” He walks a few steps, takes hold of a leaf with an improbably familiar form. “How do you like the shape of this one? I call it the Mickey Mouse.”

Karel is laconic, with a humor far drier than the Hilo day, and a fondness for Camel cigarettes. He is an illustrator by trade, draws everything from National Geographic mise-en-scenes to Smucker’s jam labels. He grew up in Prague, was a friend of Vaclav Havel and was forced to leave Czechoslovakia while it was still under Soviet control. He was always a collector—fish, crocodiles, you name it—though he doesn’t want to talk about that—or his work or himself. It is the plants only that he wants to discuss—and those he can talk of for hours. He shows me his palms, rare ones from Madagascar to Malaysia, but here at Karel’s they are in a symbiotic relationship with a myriad of other plants: Their trunks are covered with vines, creepers, flowers. Karel likes it that way. “To me,” he says, “a palm garden is a frame to put the jewelry on.

You’ll see palms everywhere around Hilo: in the gulches, by the bay, along the highway. But if you want to see the best public collection in town head to the Pana‘ewa Zoo—where you even get a white tiger into the deal. I tour the collection with Karen Piercy and her husband Dean; Karen, remember, is the one who ambushed Alan that fateful night, a former HIPS president who arrived in Hilo from Northern California in 1990 knowing next to nothing about palms. “Dean and I went to a slide show [at HIPS] that just knocked our eyes out,” Karen remembers. “All of the people there were so enthusiastic. Of all the little groups we visited, the palm society was the one that was most alive.”

True to form, Karen and Dean are now obsessed and have over 400 species of palms growing at home. They also help care for the zoo’s palm collection, HIPS’ biggest civic project. Walking through it, we see an ivory nut palm, a teddy bear palm, a pygmy date palm, a palm with a black crown shaft, a palm with a wild dreadlocked inflorescence, a palm covered in spikes, foxtail palms, sealing wax palms and more and more. Occasionally the trees and beasts match up: By the Thai tortoises, there are palms from Southeast Asia; by the lemurs, palms from Madagascar. The exoticism of the collection is only furthered by the squawks and grunts of the animals, the wandering peacocks and a hidden improbability: the fact that this all exists on dense basalt lava rock. To even dig the holes for the trees required a diamond-bit drill mounted on a truck. “When it would hit rock,” Karen remembers, “the whole truck would jump.”

So why do it?

“We’re all crazy,” Karen says. “It’s an aura of fanaticism.” She laughs then adds, “You should be warned: The founder of the International Palm Society was a journalist.” I laugh, too, thinking of the HIPS membership form I’ve just filled out—and my favorite email on the International Palm Society’s website: “You know you’ve got it bad when there’s a story on the nightly news about a murder or a hurricane, and you’re just trying to figure out what kind of palms are growing behind the reporter’s head.”

On my way out of Hilo, I stop to see Alan. I find him sitting at the kitchen table. His tenure as president of the palm society is now over—these days the office is held by a lovely peach palm farmer named Jenny Johnson—but Alan has become a HIPSter through and through. Before long he’s waxing philosophic about palms in a Joseph Campbell timbre, throwing around phrases like “strong cultural imperative” and reminding me that centuries ago Indian sages wrote out sutras on palm leaves. Listening to him, I remember back to a moment at Jeff’s. He’d put a seed in my palm, tiny and black, exactly like a peppercorn. At our feet were thousands more. Towering 100 feet above us was the tree they’d all come from: a Pigafetta elata, the world’s fastest-growing palm, which can shoot up ten feet a year. I’d taken the seed between my thumb and index finger, run it in circles, amazed to think of the wisdom, the nobility, the virility encapsulated in something so miniscule. Here in this seed was the whole story: improbability, magic, life. “People think palms are just telephone poles with heads,” Jeff had said, almost rolling his eyes in disgust as he stood surrounded by the sentinels he’d assembled. The HIPSters, of course, know better—and thanks to them, now we do, too.