In the movie The Land of Eb, the character of Jacob crisscrosses the barren landscape south of Kona in a 1968 International Scout, a truck that is a lot like him: a stalwart, battered workhorse with its own tough dignity. Jacob drives men to pick coffee beans and kids to band practice. He travels north from his bone-dry compound at the southern extreme of the island to fetch water, and he gets his children to church and himself to the doctor. He is a new immigrant to the Big Island, a Marshallese man whose home atoll was all but obliterated, and as we watch him move through the film doing everything he can to hold his family and community together, we go deep inside the Marshallese experience in Hawai‘i: These newest immigrants to the Islands have been hammered by poverty, discrimination and illness in the wake of the upheaval that followed when their home became the world’s largest nuclear testing ground. In Hawai‘i the Marshallese have struggled to retain their culture and create new lives. The story is all there in The Land of Eb, seen from the inside out, told through Jacob.

Jonithen Jackson, the actor who plays Jacob, shares a great deal with his character. Like Jacob he moved to the Big Island from the Marshalls, looking for a place to forge a better future for his family. The story Jacob tells at the beginning of the film is really Jonithen’s own: He looks into a video camera, speaking in Marshallese, but the subtitles explain: “Our story … starts before,” he says somberly, “when the Americans moved us from our island, Enewitok, and put us on the small island of Ujelang. When we got to Ujelang they left us without food, without water, and most of us that went to Ujelang starved. One day my grandmother, who was old enough to understand, she looked up into the sky, and she saw a big light that filled the heavens. At this point she knew that the bomb had destroyed our island. She knew we couldn’t return. …”

Jacob stops, overcome by the memory of the hydrogen bomb that the Navy detonated in Enewitok in 1952—an explosion that has also reverberated through Jonithen’s life. He was born on Ujelang in 1956 and grew up there. In 1980 the United States cleared people to move back to Enewitok after all of the irradiated topsoil and debris had been scraped off the island and encased in a massive concrete dome. Jonithen moved back—though the nuclear specter was always there. Forty-three nuclear tests were carried out on Enewitok between 1948 and 1958, and to this day, Jonithen notes, time spent in areas around Enewitok results in an increased reading of radioactivity in the body.

On Enewitok, Jonithen trained himself to fix all of the equipment the military had left behind; after six years he moved to the Marshallese capital of Majuro and found work as a mechanic. He was called back to Enewitok to maintain the power plant and there decided he wanted to make a better life for his children; under the terms of a post-testing political agreement, all Marshallese were given the right to immigrate to the United States. “I will go first and find the place,” Jonithen told his wife, “and then I’ll be back for you.”

He went to Bellingham, Washington, but it was too cold. He went to Honolulu, but it was too crowded. He arrived on the Big Island in 1991 and stayed at Uncle Billy’s Hotel in Kona. When he walked around everyone was friendly, wanted to talk. Strangers called out, “Hey bruddah!” with a smile. “This is the place for us,” Jonithen thought, though the Kona side of the Big Island—with its vast stretches of glistening lava rock, the newest land in the Pacific—is very different from Enewitok, which has a huge lagoon and is, like all atolls, among the oldest islands in the Pacific.

In Kona Jonithen got a job fixing buses for Polynesian Adventure Tours. He worked as a cook at Burger King and also picked coffee, oranges, macadamia nuts—whatever he could find. His wife arrived, and she worked at Burger King, too. His kids came. Others in the Enewitok community came. Jacob became a modern-day Pied Piper, such is the power of his vision, fortitude and can-do conviction: There are now six hundred people from Enewitok living on the Big Island, all having followed since Jonithen’s arrival two decades ago.

Jonithen found two lots of land in Ocean View—desolate, vog-choked—and he scoured garage sales for what he needed to build houses and transform the site into a Marshallese commune. Slowly they built a new homeland. “In our culture, in my life, in my way, I’m always thinking about everybody,” Jonithen says. “If there are no people in my place, I’m not happy.” His real passion, though, is to tell Marshallese stories and histories, and the best way he saw to do that was to make movies: He is a man with a genius for jerry-rigging and a zeal for film that would make Georges Méliès proud. He began buying cameras, usually broken ones because they were cheaper, but he preferred it that way: By fixing them he learned about their inner workings and mastered them. When a young woman from South Africa named Janine Aberg, a student from an evangelical college in Kona, came to the compound to donate computers and teach dance to the children there, Jonithen told her that he was interested in making movies. She went back to the school and spoke with a man in its film program, a young director named Andrew Williamson. Andrew drove south to Ocean View to meet Jonithen, and, to borrow a line from another film, it was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

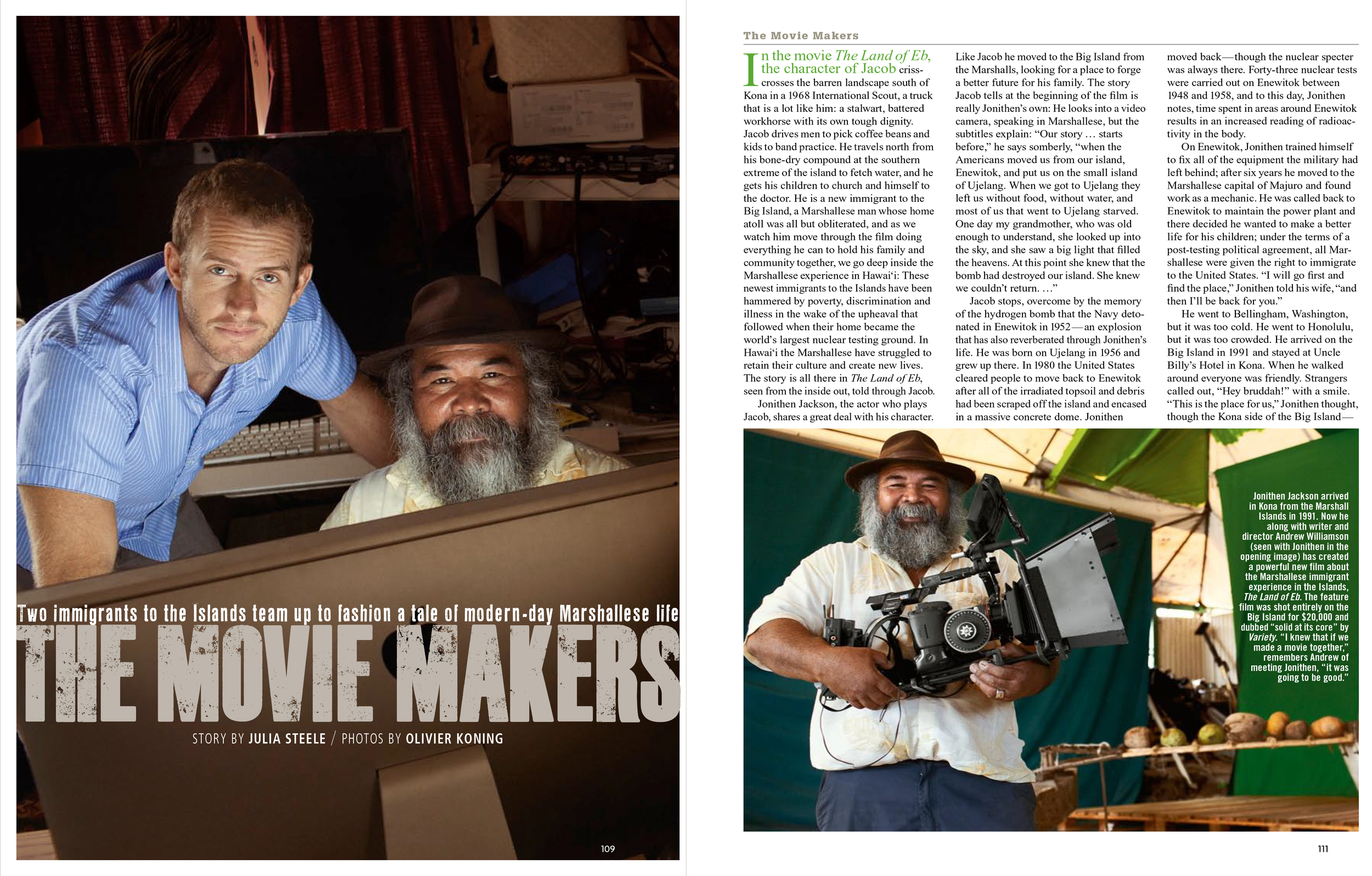

Movies made in and about the Hawaiian Islands are almost invariably created by people who come from elsewhere: From Here to Eternity, Michener’s Hawaii, The Descendants. Homegrown feature films are rare, particularly ones that are strong enough to play at film festivals with the cachet of Toronto and Chicago. The Land of Eb truly is unique: Shot on the Big Island in twenty-one days for $20,000, it is impressive at every level: direction, writing, acting, cinematography, score, editing. Variety called it “rough around the edges and solid at its core.” Jonithen inhabits Jacob seamlessly, carrying every scene with ease despite the fact that he’d never acted before. He hadn’t even wanted the role—his interest lay behind the camera—but when no one else appeared he took it on, practical and fearless. When his wife Tarke worried about how it might affect their lives to be in a movie, Jonithen told her, “It’s much better to try than not try.” She wound up playing the role of his wife in the film.

The Land of Eb was Andrew’s first feature, too, though he’d been studying film since 1996, when he first came out to Kona from Southern California as a student at the evangelical college, University of the Nations. Today he works there, teaching students who travel from around the world to take the college’s intensive three-month film course. When Andrew arrived in Ocean View to meet Jonithen in 2009, he was taken by the inventive contraptions Jonithen had built and by his clear fascination with film.

“He had a big interest and a compelling story,” remembers Andrew, “and I knew that if we made a movie together, it was going to be good.” He and colleague John Hill began spending time with Jonithen, talking, observing. They learned a history of which they had known nothing: the nuclear testing in the Marshalls, the emigration of its people, the challenges the Marshallese on the Big Island face. The pair began drafting a script. They ran everything they wrote through Jonithen and his daughter Rojel (who is also in the film, and plays Jacob’s oldest daughter). “We wanted to make sure everything we wrote could have happened,” explains Andrew.

At the beginning of the film, Jacob learns his cancer has returned. Determined not to go back to chemotherapy, he looks for extra work so he can pay off his land before he dies and leave it debt-free for his family. He makes a deal with a coffee farmer to gather a group to pick the crop, but as his illness progresses things spiral. Jacob is the linchpin of his community, and we watch him struggle to hold everything together for the people around him, including a young daughter who has a new child and a wastrel boyfriend. At one point, overwhelmed, Jacob sits on the ground with his daughter, looking at a tree growing out of the barren ground. “That tree is like me,” he tells her, shaking his head. “Even though there was nothing but rock, it found a way to grow. I don’t want any of you to struggle like that and grow up gnarled and tough like I had to. Because I know you can grow and be so much bigger than me. If you could only see … we can’t ever stop moving forward.”

The Land of Eb was very much a collaboration between Jonithen and the writers; while it is not a documentary, its storyline does draw on real life: Jonithen did have cancer a few years ago, Marshallese agricultural workers have been cheated by unscrupulous landowners and teen pregnancies are an issue. The film was shot in 2010 at a number of locations: at Jonithen’s compound, on the highway that runs from Ocean View to Kona, on coffee farms, at the Outrigger Hotel on Ali‘i Drive, at a community center near the old Kona airport that serves as a Marshallese church on Sunday mornings. Everyone worked diligently, and no one—cast nor crew—was paid. The International Scout was found on a farm in Ocean View; when Andrew bought it for $200, it was broken and parts weren’t available. Jonithen spent a couple of mornings under it and got it running. At one point during filming its engine caught fire. Andrew laughs at the memory: “This was real low-budget filmmaking.”

Fifteen hours of footage, shot in high-def on a Canon DSLR camera, were edited to a tight ninety minutes: The finished film has a purity and an economy to its emotions—and a subtlety too, not necessarily what you might expect from a crew drawn from an evangelical college. “Some of the university’s programs are very evangelistic,” notes Andrew, “but the program I’m with is more about telling stories that make people think. I don’t want a film to be a sermon. I wouldn’t call myself an activist. I wasn’t a champion of the Marshallese before I started this film, but I was attracted to the story and to Jonithen.”

The Land of Eb was finished and released in 2012. In addition to playing in Toronto and Chicago, it screened to acclaim at a handful of other festivals, including the Hawaii International Film Festival last fall, where it was nominated for best feature film, and the World Oceania International Film Festival in Fiji. It hasn’t been picked up by a distributor, so Andrew has decided to self-distribute it: DVDs are now available through www.thelandofeb.com and the film’s trailer is there, too.

What comes next? Andrew is thinking of making his second feature, set in the Hawai‘i of the 1830s, a time of radical change. At some point, he says, he’d also like to make another movie with Jonithen. And Jonithen? On his compound in Ocean View, he has now built a film studio that measures thirty by sixty feet. He created it for less than $200, but it’s the real thing: It’s got three large green screens made from fabric bought from Walmart for $1 a yard. It’s got a dolly fashioned from an old motorcycle. It’s got a stage made from leftover plywood and a roof salvaged from a local Catholic church and held up by twenty-three metal beams he bought for five bucks apiece, sanded, painted and welded together; he built its three camera booms from salvaged metal, too.

Jonithen is getting ready to direct his own films now. He’s already written his first, a short tentatively titled Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow; it’ll star himself and his grandson (who had a small but memorable role in The Land of Eb as the boy with the three-prong fishing spear) and use magical realism to look into the future. For his role Jonithen has been growing a long beard, which will feature in the film’s plot. He’s excited to begin production. “There are so many stories in the Marshall Islands,” he says. “We should start making them now. If you always think about what you really believe in, you will get there—that’s what I believe.”