The plane to Huahine is filled with paddling’s elite, row upon row of tattooed biceps, sculpted bodies, focused faces. In two days, these athletes will take on the most punishing outrigger canoe race in the world.

The man sitting across the aisle from me leans over. “Paddling is like a drug, you know?” he offers. “You get addicted. Actually, there is no pleasure in paddling, only the challenge and the pride when you finish the race. It’s hard. It’s tough.”

In Huahine’s tiny airport, men mill about looking for rides, holding their paddles with ease and care, the way they might a child’s hand. They are headed for Fare, Huahine’s capital, where the race will begin in about forty-eight hours. Fare is a backwater with little more than one main street, but now it has become a fairgrounds, with music, food stands, colored lights strung from the trees and thousands of people wandering about: paddlers, fans, officials, kids, mothers, grandmothers, journalists. A massive French battleship, the Dumont d’Urville, is at the dock; it has just arrived from Papeete, bearing dozens of canoes for the race. People are drinking Hinano, swimming in the harbor, eating watermelon. A bad cover of “Islands in the Stream” plays in the distance. I talk with one paddler who has just emerged from the sea. His black hair hangs down to his waist; he wrings it out as we speak.

“Is it true,” I ask, “that there’s no pleasure in paddling?”

He nods his head. “It’s rough,” he agrees, “it’s tough. Vraiment, ce n’est pas une plaisir. Mais c’est la rame de nos culture.”

I rack my brain, searching years of French vocab, but I have no idea what rame means.

“La quoi?” I ask. The what?

“La rame, la rame.” He can see my confusion. He grabs a paddle from someone walking by, holds it toward me. “La rame.”

I get it. “La rame,” I say, grinning, “the paddle.”

He grins back. “Vois alors, you understand. Paddling is itself the paddle of our culture. It takes us where we’re going; it keeps us who we are. We don’t paddle for pleasure. We paddle because we’re proud to honor the culture.”

The canoe in Tahiti is pragmatic, iconic, ubiquitous. It is the lowly daily transport and the lofty national symbol, used both for quick jaunts out to the reef to get dinner and to populate an Oceanic triangle stretching from New Zealand to Rapa Nui to Hawai‘i. In a world of water, it transforms a man into an ocean creature.

In general, larger canoes are sailed, smaller canoes paddled. It is those smaller canoes, propelled by human muscle, that have bred such intense sportsmanship and fierce competition. Paddling is the sport of Tahiti, the way surfing is the sport of Hawai‘i, hockey the sport of Canada—so associated with its homeland that even when it travels the world, it retains its national identity still. And paddling’s ultimate challenge—its Triple Crown, its Stanley Cup—is Tahiti’s Hawaiki Nui Va‘a. Hawai‘i’s Moloka‘i Hoe doesn’t even come close.

The race takes three days, covers 80 miles over a grueling course. On day one, paddlers slog 28 miles across a rough-and-tumble stretch of open ocean between the islands of Huahine and Raiatea. Day two, they take on a 16-mile sprint from Raiatea to Taha‘a, inside the massive lagoon that encircles the two islands. Day three—the longest—they paddle 36 miles from Taha‘a, out through the pass, into the open ocean and toward Bora Bora. There, in a blitz of drumming, dancing, embraces and flowers, the race finishes.

The canoes are six-man outriggers, powered by sextets that move with the precision of pistons and the strength of Samsons. Unlike the Moloka‘i Hoe, which allows crew changes every fifteen minutes, each individual leg of the Hawaiki Nui must be paddled by the same six men—and if anyone gets into trouble on the water and needs to drop out, the leg continues only with whoever’s left. Teams can and do have more than six members overall, and substitutions can be made on alternate days—but machismo being what it is, many teams make a point of competing with the same six men throughout all three race days. “You never forget this race,” says one of the paddlers who has traveled from Hawai‘i to Tahiti to compete. “It’s the ultimate.”

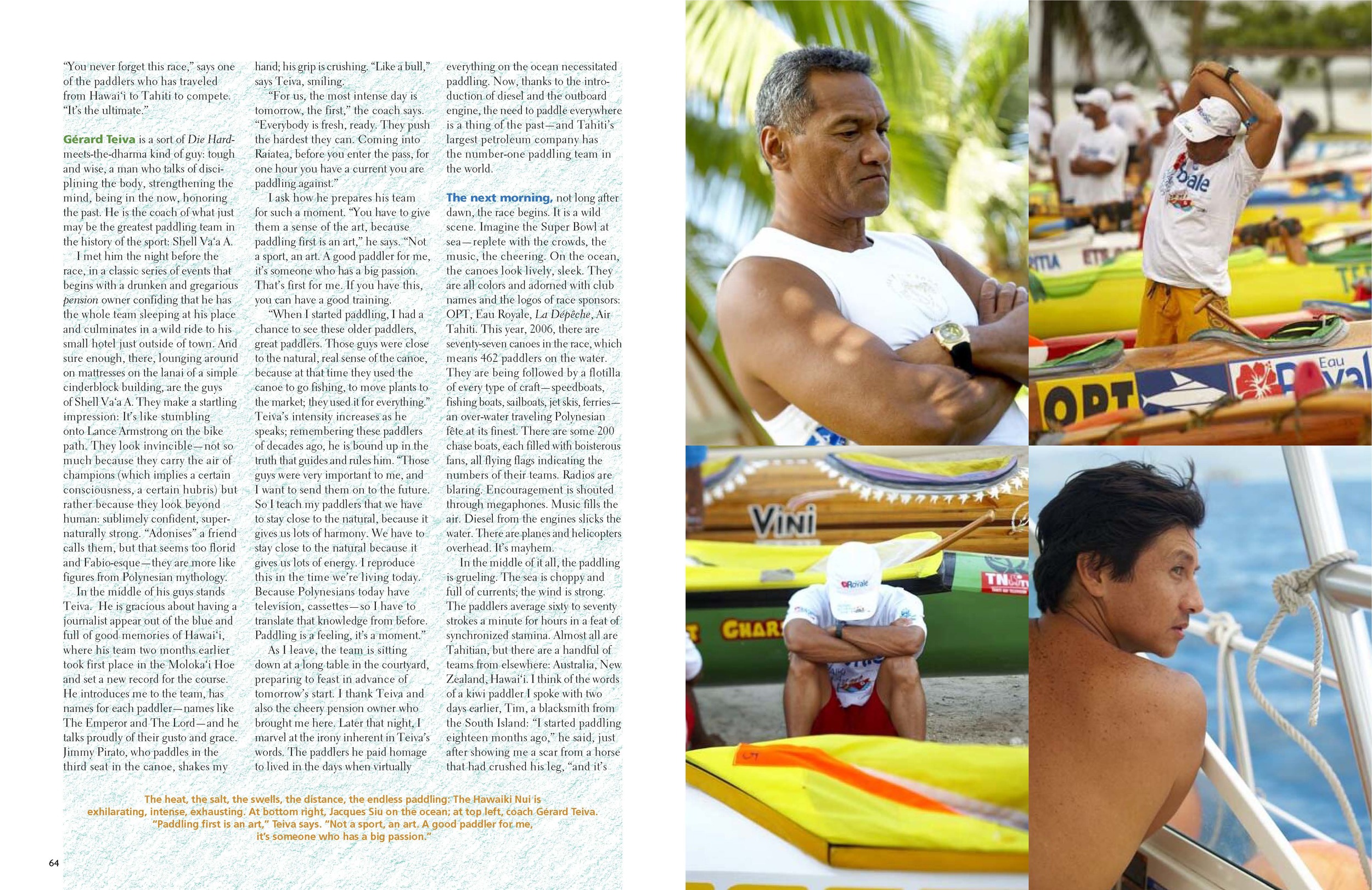

Gérard Teiva is a sort of Die Hard-meets-the-dharma kind of guy: tough and wise, a man who talks of disciplining the body, strengthening the mind, being in the now, honoring the past. He is the coach of what just may be the greatest paddling team in the history of the sport: Shell Va‘a A.

I meet him the night before the race, in a classic series of events that begins with a drunken and gregarious pension owner confiding that he has the whole team sleeping at his place and culminates in a wild ride to his small hotel just outside of town. And sure enough, there, lounging around on mattresses on the lanai of a simple cinderblock building, are the guys of Shell Va‘a A. They make a startling impression: It’s like stumbling onto Lance Armstrong on the bike path. They look invincible—not so much because they carry the air of champions (which implies a certain consciousness, a certain hubris) but rather because they look beyond human: sublimely confident, supernaturally strong. “Adonises” a friend calls them, but that seems too florid and Fabio-esque—they are more like figures from Polynesian mythology.

In the middle of his guys stands Teiva. He is gracious about having a journalist appear out of the blue and full of good memories of Hawai‘i, where his team two months earlier took first place in the Moloka‘i Hoe and set a new record for the course. He introduces me to the team, has names for each paddler—names like The Emperor and The Lord—and he talks proudly of their gusto and grace. Jimmy Pirato, who paddles in the third seat in the canoe, shakes my hand; his grip is crushing. “Like a bull,” says Teiva, smiling.

“For us, the most intense day is tomorrow, the first,” the coach says. “Everybody is fresh, ready. They push the hardest they can. Coming into Raiatea, before you enter the pass, for one hour you have a current you are paddling against.”

I ask how he prepares his team for such a moment. “You have to give them a sense of the art, because paddling first is an art,” he says. “Not a sport, an art. A good paddler for me, it’s someone who has a big passion. That’s first for me. If you have this, you can have a good training.

“When I started paddling, I had a chance to see these older paddlers, great paddlers. Those guys were close to the natural, real sense of the canoe, because at that time they used the canoe to go fishing, to move plants to the market, they used it for everything.” Teiva’s intensity increases as he speaks; remembering these paddlers of decades ago, he is bound up in the truth that guides and rules him. “Those guys were very important to me, and I want to send them on to the future. So I teach my paddlers that we have to stay close to the natural, because it gives us lots of harmony. We have to stay close to the natural because it gives us lots of energy. I reproduce this in the time we’re living today. Because Polynesians today have television, cassettes—so I have to translate that knowledge from before. Paddling is a feeling, it’s a moment.”

As I leave, the team is sitting down at a long table in the courtyard, preparing to feast in advance of tomorrow’s start. I thank Teiva and also the cheery pension owner who brought me here. Later that night, I marvel at the irony inherent in Teiva’s words. The paddlers he paid homage to lived in the days when virtually everything on the ocean necessitated paddling. Now, thanks to the introduction of diesel and the outboard engine, the need to paddle everywhere is a thing of the past—and Tahiti’s largest petroleum company has the number-one paddling team in the world.

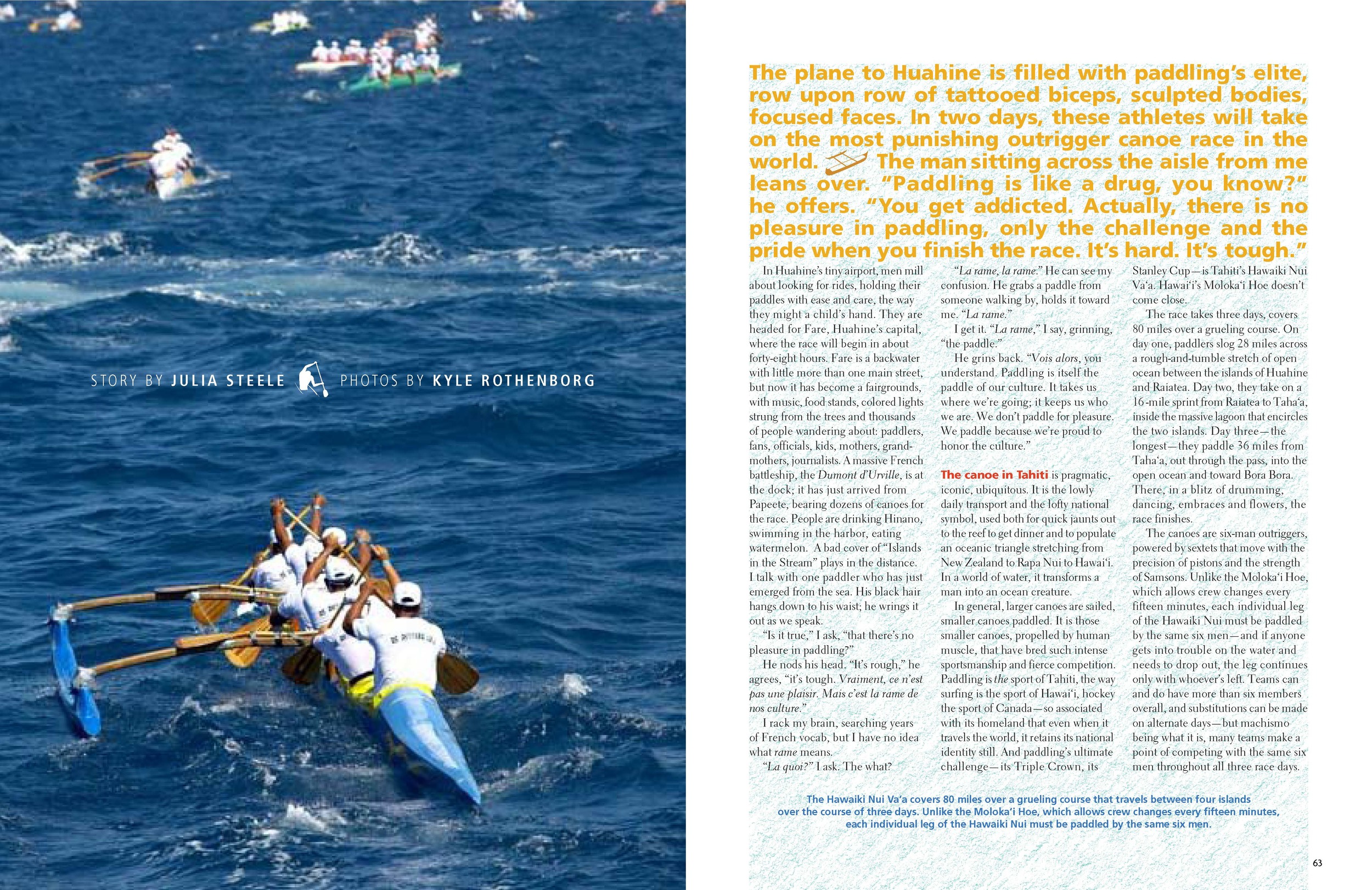

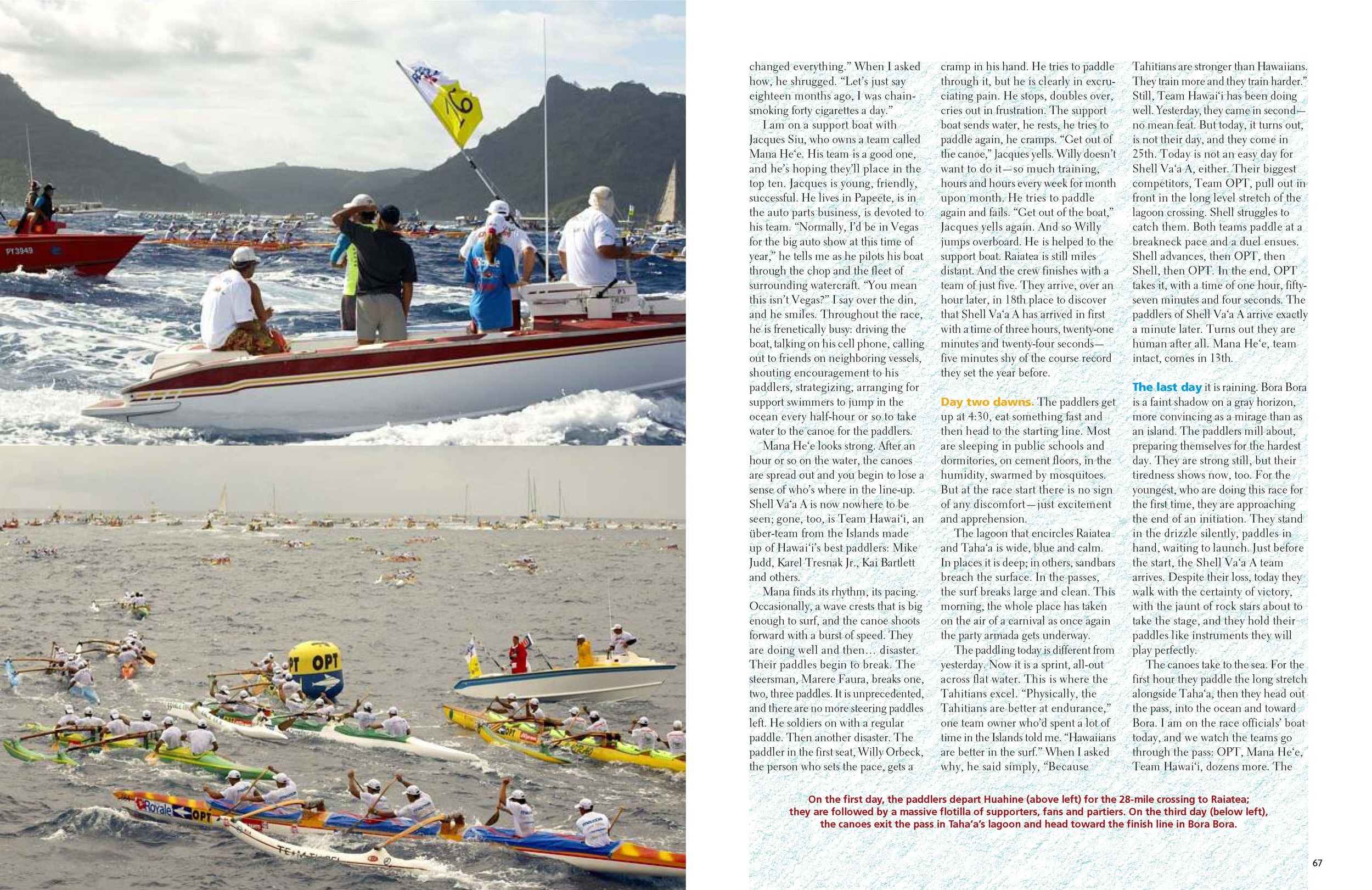

The next morning, not long after dawn, the race begins. It is a wild scene. Imagine the Super Bowl at sea—replete with the crowds, the music, the cheering. On the ocean, the canoes look cheerful, sleek. They are all colors and adorned with club names and the logos of race sponsors: OPT, Eau Royale, La Dépêche, Air Tahiti. This year, 2006, there are seventy-seven canoes in the race, which means 462 paddlers on the water. They are being followed by a flotilla of every type of craft—speedboats, fishing boats, sailboats, jet skis, ferries—an over-water traveling Polynesian fête at its finest. There are some 200 chase boats, each filled with boisterous fans, all flying flags indicating the numbers of their teams. Radios are blaring. Encouragement is shouted through megaphones. Music fills the air. Diesel from the engines slicks the water. There are planes and helicopters overhead. It’s mayhem.

In the middle of it all, the paddling is grueling. The sea is choppy and full of currents; the wind is strong. The paddlers average sixty to seventy strokes a minute for hours in a feat of synchronized stamina. Almost all are Tahitian, but there are a handful of teams from elsewhere: Australia, New Zealand, Hawai‘i. I think of the words of a kiwi paddler I spoke with two days earlier, Tim, a blacksmith from the South Island: “I started paddling eighteen months ago,” he said, just after showing me a scar from a horse that had crushed his leg, “and it’s changed everything.” When I asked how, he shrugged. “Let’s just say eighteen months ago, I was chain-smoking forty cigarettes a day.”

I am on a support boat with Jacques Siu, who owns a team called Mana He‘e. His team is a good one, and he’s hoping they’ll place in the top ten. Jacques is young, friendly, successful. He lives in Papeete, is in the auto parts business, is devoted to his team. “Normally, I’d be in Vegas for the big auto show at this time of year,” he tells me as he pilots his boat through the chop and the fleet of surrounding watercraft. “You mean this isn’t Vegas?” I say over the din, and he smiles. Throughout the race, he is frenetically busy: driving the boat, talking on his cell phone, calling out to friends on neighboring vessels, shouting encouragement to his paddlers, strategizing, arranging for support swimmers to jump in the ocean every half-hour or so to take water to the canoe for the paddlers.

Mana He‘e looks strong. After an hour or so on the water, the canoes are spread out and you begin to lose a sense of who’s where in the line-up. Shell Va‘a A is now nowhere to be seen; gone, too, is Team Hawai‘i, an über-team from the Islands made up of Hawai‘i’s best paddlers: Mike Judd, Karel Tresnak Jr., Kai Bartlett and others.

Mana finds its rhythm, its pacing. Occasionally, a wave crests that is big enough to surf, and the canoe shoots forward with a burst of speed. They are doing well and then… disaster. Their paddles begin to break. The steersman, Marere Faura, breaks one, two, three paddles. It is unprecedented, and there are no more steering paddles left. He soldiers on with a regular paddle. Then another disaster. The paddler in the first seat, Willy Orbeck, the person who sets the pace, gets a cramp in his hand. He tries to paddle through it, but he is clearly in excruciating pain. He stops, doubles over, cries out in frustration. The support boat sends water, he rests, he tries to paddle again, he cramps. “Get out of the canoe,” Jacques yells. Willy doesn’t want to do it—so much training, hours and hours every week for month upon month. He tries to paddle again and fails. “Get out of the boat,” Jacques yells again. And so Willy jumps overboard. He is helped to the support boat. Raiatea is still miles distant. And the crew finishes with a team of just five. They arrive, over an hour later, in 18th place to discover that Shell Va‘a A has arrived in first with a time of three hours, twenty-one minutes and twenty-four seconds—five minutes shy of the course record they set the year before.

Day two dawns. The paddlers get up at 4:30, eat something fast and then head to the starting line. Most are sleeping in public schools and dormitories, on cement floors, in the humidity, swarmed by mosquitoes. But at the race start there is no sign of any discomfort—just excitement and apprehension.

The lagoon that encircles Raiatea and Taha‘a is wide, blue and calm. In places it is deep; in others, sandbars breach the surface. In the passes, the surf breaks large and clean. This morning, the whole place has taken on the air of a carnival as once again the party armada gets underway.

The paddling today is different from yesterday. Now it is a sprint, all out across flat water. This is where the Tahitians excel. “Physically, the Tahitians are better at endurance,” one team owner who’d spent a lot of time in the Islands told me. “Hawaiians are better in the surf.” When I asked why, he said simply, “Because Tahitians are stronger than Hawaiians. They train more and they train harder.” Still, Team Hawai‘i has been doing well. Yesterday, they came in second—no mean feat. But today, it turns out, is not their day, and they come in 25th. Today is not an easy day for Shell Va‘a A, either. Their biggest competitors, Team OPT, pull out in front in the long level stretch of the lagoon crossing. Shell struggles to catch them. Both teams paddle at a breakneck pace and a duel ensues. Shell advances, then OPT, then Shell, then OPT. In the end, OPT takes it, with a time of one hour, fifty-seven minutes and four seconds. The paddlers of Shell Va‘a A arrive exactly a minute later. Turns out they are mortal after all. Mana He‘e, team intact, comes in 13th.

The last day it is raining. Bora Bora is a faint shadow on a grey horizon, more convincing as a mirage than as an island. The paddlers mill about, preparing themselves for the hardest day. They are strong still, but their tiredness shows now, too. For the youngest, who are doing this race for the first time, they are approaching the end of an initiation. They stand in the drizzle, rashguards on, paddles in hand, waiting to launch. Just before the start, the Shell Va‘a A team arrives. Despite their loss, today they walk with the certainty of victory, with the jaunt of rock stars about to take the stage, and they hold their paddles like instruments they will play perfectly.

The canoes take to the sea. For the first hour they paddle the long stretch alongside Taha‘a, then they head out the pass, into the ocean and toward Bora. I am on the race officials’ boat today, and we watch the teams go through the pass: OPT, Mana He‘e, Team Hawai‘i, dozens more. The Australian team, the Pacific Dragons from Sydney, is the last through. Earlier that morning, I’d spoken with one of their paddlers, Grant Billen. “It’s been wonderful,” he enthused. “It’s been everything we’d hoped the experience of paddling an outrigger in Polynesia would be. Sleeping in school halls, taking meals together: The teams have treated us so well.” Where the Dragons place in the race seems, to him, to be irrelevant.

There are medics on the officials’ boat, and I ask what they most commonly treat. “Cramps,” they say, “blisters, cuts, rashes, dehydration.” But today, with the downpour, dehydration won’t be a problem. The ocean is glassy in the rain, calm and colorless. As we head toward Bora in advance of the paddlers’ arrival, at one point we pull alongside Shell Va‘a A. They are stroking with perfect precision, sixty-eight to seventy strokes a minute, faster than a heartbeat, and their rhythm does not break. I think back to three days earlier, that sense of seeing bodies that had transcended mortal limitations: Watching now, their strength, their synchronicity seems pulled from elsewhere.

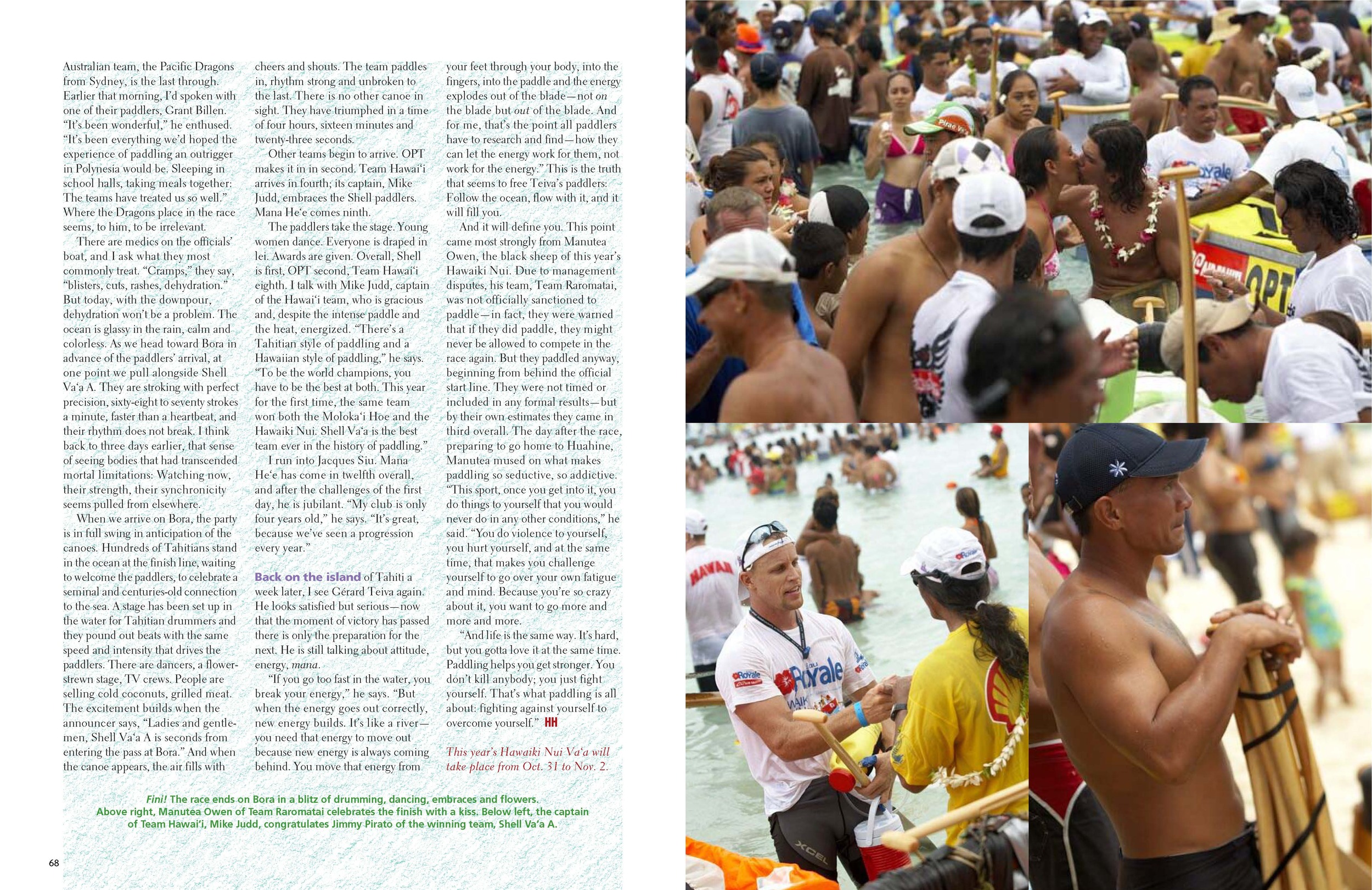

When we arrive on Bora, the party is in full swing in anticipation of the canoes. Hundreds of Tahitians stand in the ocean at the finish line, waiting to welcome the paddlers, to celebrate a seminal and centuries-old connection to the sea. A stage has been set up in the water for Tahitian drummers and they pound out beats with the same speed and intensity that drives the paddlers. There are dancers, a flower-strewn stage, TV crews. People are selling cold coconuts, grilled meat. The excitement builds when the announcer says, “Ladies and gentlemen, Shell Va‘a A is seconds from entering the pass at Bora.” And when the canoe appears, the air fills with cheers and shouts. The team paddles in, rhythm strong and unbroken to the last. There is no other canoe in sight. They have triumphed in a time of four hours, sixteen minutes and twenty-three seconds.

Other teams begin to arrive. OPT makes it in in second. Team Hawai‘i arrives in fourth; its captain, Mike Judd, embraces the Shell paddlers. Mana He‘e comes ninth.

The paddlers take the stage. Young women dance. Everyone is draped in lei. Awards are given. Overall, Shell is first, OPT second, Team Hawai‘i eighth. I talk with Mike Judd, captain of the Hawai‘i team, who is gracious and, despite the intense paddle and the heat, energized. “There’s a Tahitian style of paddling and a Hawaiian style of paddling,” he says. “To be the world champions, you have to be the best at both. This year for the first time, the same team won both the Moloka‘i Hoe and the Hawaiki Nui. Shell Va‘a is the best team ever in the history of paddling.”

I run into Jacques Siu. Mana He‘e has come in twelfth overall, and after the challenges of the first day, he is jubilant. “My club is only four years old,” he says. “It’s great, because we’ve seen a progression every year.”

Back on the island of Tahiti a week later, I see Gérard Teiva again. He looks satisfied but serious—now that the moment of victory has passed there is only the preparation for the next. He is still talking about attitude, energy, mana.

“If you go too fast in the water, you break your energy,” he says. “But when the energy goes out correctly, new energy builds. It’s like a river—you need that energy to move out because new energy is always coming behind. You move that energy from your feet through your body, into the fingers, into the paddle and the energy explodes out of the blade—not on the blade but out of the blade. And for me, that’s the point all paddlers have to research and find—how they can let the energy work for them, not work for the energy.” This is the truth that seems to free Teiva’s paddlers: Follow the ocean, flow with it, and it will fill you.

And it will define you. This point came most strongly from Manutea Owen, the black sheep of this year’s Hawaiki Nui. Due to management disputes, his team, Team Raromatai, was not officially sanctioned to paddle—in fact, they were warned that if they did paddle, they might never be allowed to compete in the race again. But they paddled anyway, beginning from behind the official start line. They were not timed or included in any formal results—but by their own estimates they came in third overall. The day after the race, preparing to go home to Huahine, Manutea mused on what makes paddling so seductive, so addictive. “This sport, once you get into it, you do things to yourself that you would never do in any other conditions,” he said. “You do violence to yourself, you hurt yourself, and at the same time, that makes you challenge yourself to go over your own fatigue and mind. Because you’re so crazy about it, you want to go more and more and more.

“And life is the same way. It’s hard, but you gotta love it at the same time. Paddling helps you get stronger. You don’t kill anybody; you just fight yourself. That’s what paddling is all about: fighting against yourself to overcome yourself.”