The color of it all was very handsome and delicate—all like a dream— … I love the things that grow—the big dark trees—the big leaves—the black stream beds with the rushing white water. … —I love the wind and the salt air— … —we have walked and climbed—and sat in the sun—and always the places were so good— Georgia O’Keeffe, letters from Häna, March, 1939

On January 30, 1939, Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz were headed to New York’s Grand Central Station. Half a world away, Hitler was ranting in the Reichstag, vowing in an infamous speech “the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe,” but the darkness that would soon eclipse the globe had not yet reached New York. In 1939 O’Keeffe was well on her way to becoming one of America’s most acclaimed, inventive artists; Stieglitz, twenty-three years her senior and a renowned photographer, was her Svengali. The two had been married for fifteen years, and while theirs was a union famously fraught with tension, it was also, as O’Keeffe’s letters to her husband over the next two months would show, filled with affection and tenderness.

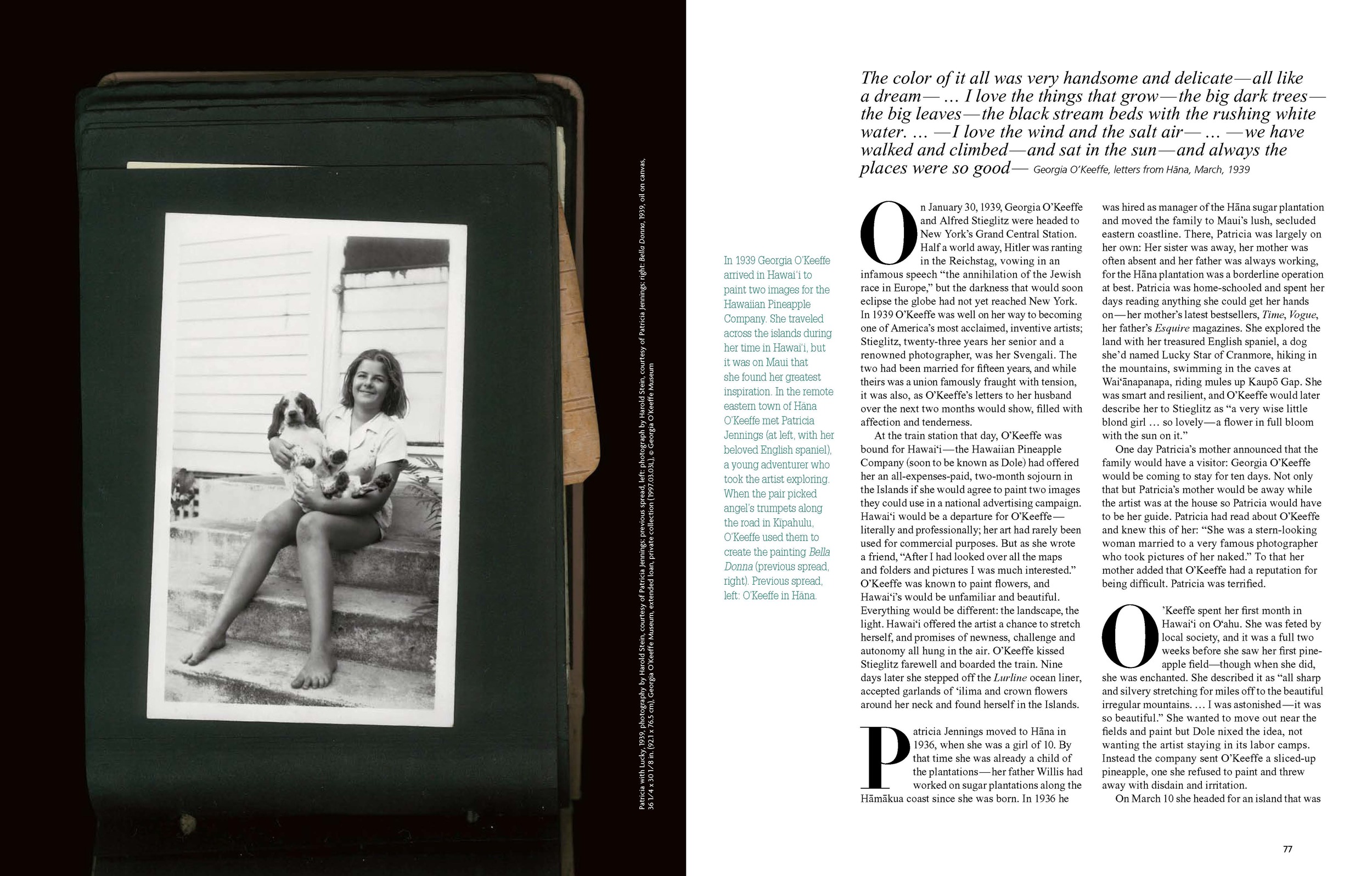

At the train station that day, O’Keeffe was bound for Hawai‘i—the Hawaiian Pineapple Company (soon to be known as Dole) had offered her an all-expenses-paid, two-month sojourn in the Islands if she would agree to paint two images they could use in a national advertising campaign. Hawai‘i would be a departure for O’Keeffe—literally and professionally; her art had rarely been used for commercial purposes. But as she wrote a friend, “After I had looked over all the maps and folders and pictures I was much interested.” O’Keeffe was known to paint flowers, and Hawai‘i’s would be unfamiliar and beautiful. Everything would be different: the landscape, the light. Hawai‘i offered the artist a chance to stretch herself, and promises of newness, challenge and autonomy all hung in the air. O’Keeffe kissed Stieglitz farewell and boarded the train. Nine days later she stepped off the Lurline ocean liner, accepted garlands of ‘ilima and hibiscus flowers around her neck and found herself in the Islands.

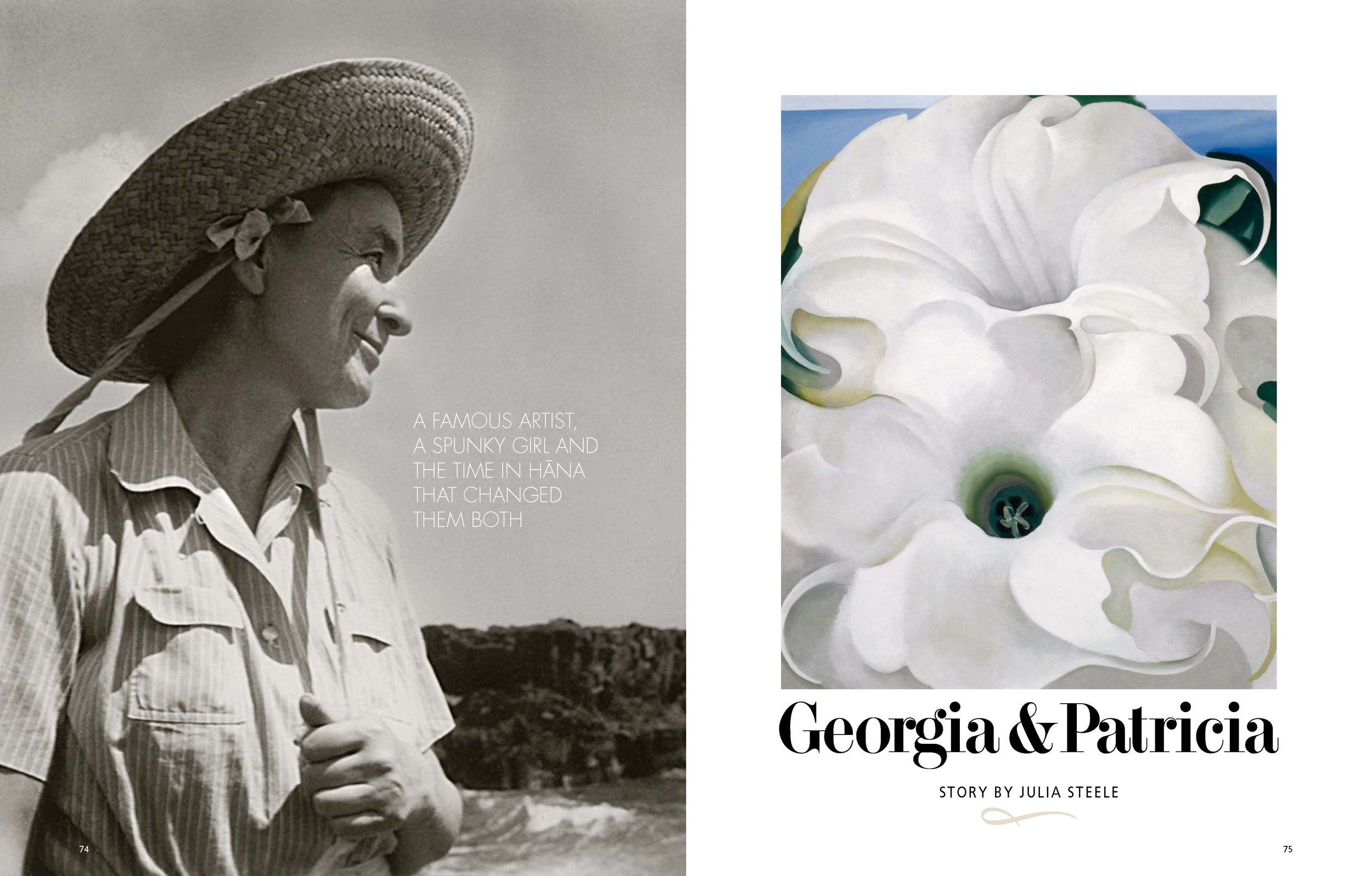

Patricia Jennings moved to Häna in 1936, when she was a girl of 10. By that time she was already a child of the plantations—her father Willis had worked on sugar plantations along the Hämäkua coast since she was born. In 1936 he was hired as manager of the Häna sugar plantation and moved the family to Maui’s lush, secluded eastern coastline. There, Patricia was largely on her own: Her sister was away, her mother was often absent and her father was always working, for the Häna plantation was a borderline operation at best. Patricia was home-schooled and spent her days reading anything she could get her hands on—her mother’s latest bestsellers, Time, Vogue, her father’s Esquire magazines. She explored the land with her treasured English spaniel, a dog she’d named Lucky Star of Cranmore, hiking in the mountains, swimming in the caves at Wai‘änapanapa, riding mules up Kaupö Gap. She was smart and resilient, and O’Keeffe would later describe her to Stieglitz as “a very wise little blond girl … so lovely—a flower in full bloom with the sun on it.”

One day Patricia’s mother announced that the family would have a visitor: Georgia O’Keeffe would be coming to stay for ten days. Not only that but Patricia’s mother would be away while the artist was at the house so Patricia would have to be her guide. Patricia had read about O’Keeffe and knew this of her: She was a stern-looking woman married to a very famous photographer who took pictures of her naked. To that her mother added that O’Keeffe had a reputation for being difficult. Patricia was terrified.

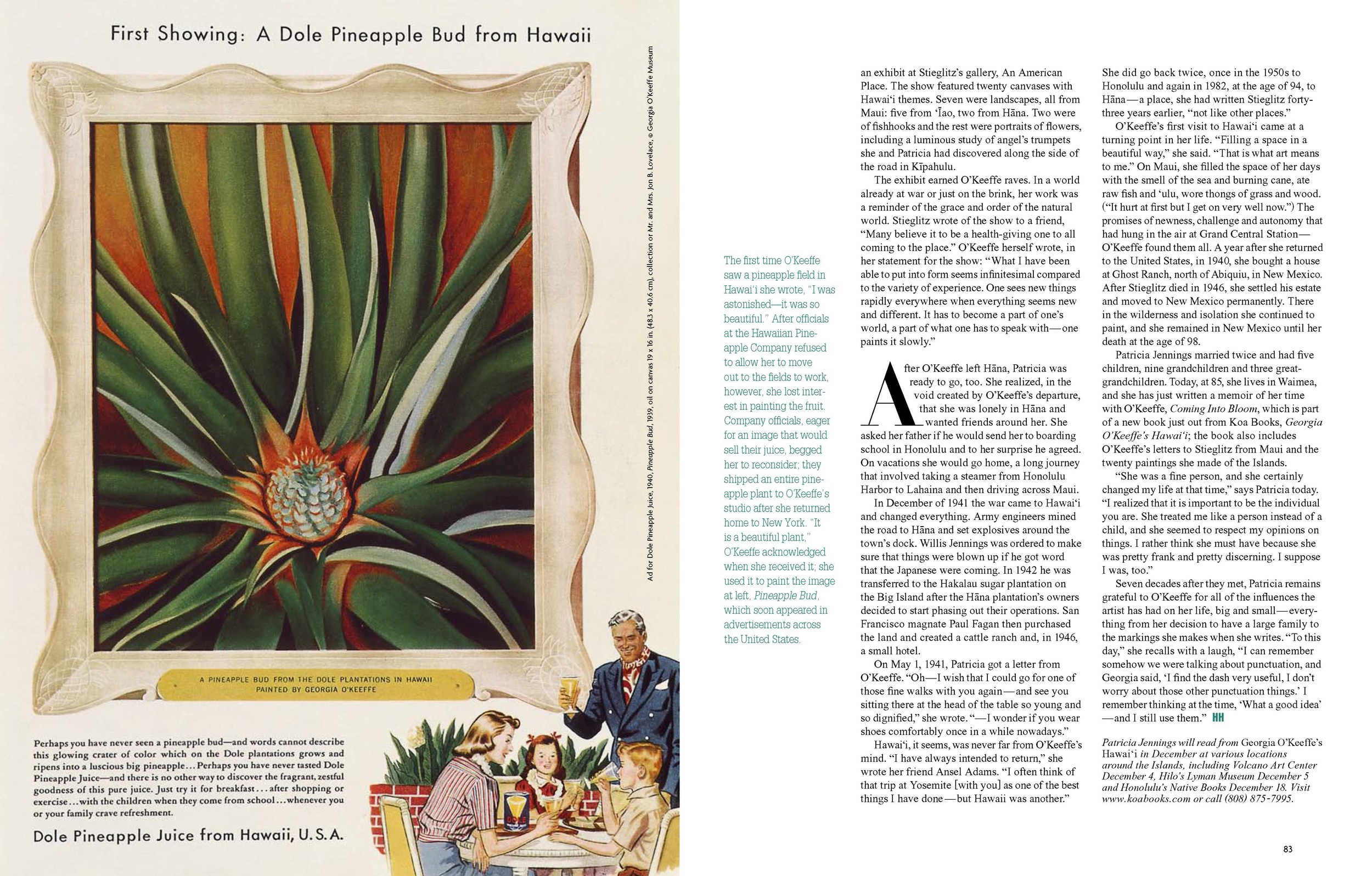

O’Keeffe spent her first month in Hawai‘i on O‘ahu. She was feted by local society, and it was a full two weeks before she saw her first pineapple field—though when she did, she was enchanted. She described it as “all sharp and silvery stretching for miles off to the beautiful irregular mountains. … I was astonished—it was so beautiful.” She wanted to move out near the fields and paint but Dole nixed the idea, not wanting the artist staying in its labor camps. Instead the company sent O’Keeffe a sliced-up pineapple, one she refused to paint and threw away with disdain and irritation.

On March 10 she headed for an island that was then much more rural and wild: Maui. On the recommendation of the artist Robert Lee Eskridge, she was bound for its most remote spot, Häna. “Stay with the Jennings,” he had urged, and O’Keeffe had agreed, hoping she would find total freedom to go where she liked and paint whatever appealed to her. Flying in to the island she was captivated. The morning she arrived she sent Stieglitz a postcard with a picture of Haleakalä. “This seems to be the best yet,” she wrote on the back. “9 in the morning on a new island seems good.”

O’Keeffe headed out on the road to Häna—still a fairly recent engineering miracle, having been completed just twelve years earlier in 1927. The sixty-mile drive fed her fascination, almost intoxication, with the landscape. “It is queer country,” she wrote Stieglitz, “—hard to describe because it varies so—and all the foliage changes—sometimes grass—sometimes cane—sometimes bamboo—there are many waterfalls—masses of rank trees and bushes—all new to me— … always the sea with usually its black rim of lava at the edge.”

In Häna that day, Patricia Jennings was awaiting O’Keeffe’s arrival, paralyzed with nervousness and trying, with no luck, to bury her mind in her copy of Heidi. A little before lunch, O’Keeffe appeared in the driveway. Patricia noted her sunken eyes, long narrow nose and the deep creases between her eyebrows; O’Keeffe seemed, to her, to be exhausted. She led the artist to the small cottage on the property where she would stay, pointing out mango, lychee, tamarind, avocado and star fruit trees as they crossed the lawn. O’Keeffe seemed happy in the cottage—and Patricia was relieved.

That night, over a meal of roast pork, potatoes, chopped lü‘au greens, green beans and taro biscuits, the two began to get to know each other. O’Keeffe was rested and in an expansive mood; she spoke freely and easily with all who were there for dinner. Patricia was mesmerized by O’Keeffe’s long, elegant hands and, abashed, remembered a photo by Stieglitz she’d seen of them in Time, crossed over O’Keeffe’s naked breasts. When the talk turned to art, O’Keeffe asked Patricia what she thought of her paintings. “I know you paint flowers and skulls in the desert,” Patricia answered, and then, remembering something else she’d seen in Time, she continued, “and that you have a wonderful brush technique.” O’Keeffe, Patricia remembers, “laughed uproariously. I didn’t understand why, but I decided she was beginning to like me.”

The next morning Willis Jennings gave O’Keeffe the keys to his wife’s sedan and assured her, before he left for work, that “Patricia knows all the spots of interest as well as any of us.” O’Keeffe packed her art supplies in the car’s trunk and then, much to Patricia’s indignation, banned Lucky from coming along on their excursion. The pair went first to the caves and black sand beach of Wai‘änapanapa. On the trail down to the sea, Patricia pointed out the hala trees, noting that with their aerial roots they reminded her of witches’ broomsticks and made her feel like she was in an enchanted forest. Later O’Keeffe described the hala as “a busy sort of palm—thick enough with foliage to be a house—not very tall—good thick shade under them—” though she never painted the tree. She did, however, paint along the coast, and at those times Patricia was sent off to explore on her own; O’Keeffe would not allow anyone to watch her paint. “Yesterday I went out painting in the morning—a little thing about 4 x 6,” she wrote Stieglitz of her first plein air canvas in Häna. “The most exciting thing here is the black lava shapes along the water and the cane fields. The lava does all sorts of queer things as it touches the water and its blackness with a little bright green to it is startling against the blue and foaming white of the water.

“It was a good morning poking about with the little girl—In the afternoon [Willis] took us for a long walk about 3 1/2 hours through all sorts of jungle—up and down very steep hills—along the sea—past water falls and deep gorges— … —we all had a very good time.”

As O’Keeffe explored Häna, she found more and more to beguile her. There were sea caves with shiny black stones called Pele’s tears, traditional canoe hale dotting the beaches, cool streams and pools in the mountains and flowers everywhere: hibiscus, plumeria, heliconia, ginger. She and Patricia developed a rhythm: The 12-year-old would take the 51-year-old out into the landscape, O’Keeffe would set up her easel and paints, and Patricia would find ways to keep herself busy. After she disappeared into Wailua Gulch, O’Keeffe warned her not to stray too far though still forbade her to watch.

“It is really so nice here—country—busy—busy with so many different kinds of things—… I must say I feel far away in another world here— … always we go to a new place,” O’Keeffe wrote Stieglitz after she had been in Häna eight days. Patricia—and when time allowed, Willis—took O’Keeffe to Kaupö, Kïpahulu and Nähiku. The trio swam at the pools at ‘Ohe‘o Gulch and at Hämoa Beach. They visited the Pi‘ilanihale Heiau, which was then overgrown, not yet restored. Throughout, Patricia and O’Keeffe forged a stronger and stronger bond of friendship. For O’Keeffe it was a time to bask in the solace of nature, delight in her own creativity and recalibrate time. “It is hard to tell about the islands—the people have a kind of gentleness that isn’t usual on the mainland—,” she wrote Stieglitz. “I feel that my tempo must definitely change to put down anything of what is here—I don’t know whether I can or not—but it is certainly a different world—and I am glad I came.” For Patricia, O’Keeffe’s friendship was stimulating and affirming. “She listened to everything I said as though each word was really important,” remembers Patricia. They had adventures, shared their thoughts on life and they were kind to each other: When Patricia ate too many wild guavas and threw up, O’Keeffe comforted her; when O’Keeffe was nervous fording a stream, Patricia reassured her.

“Monday morning—In an hour or so I’ll be leaving Hana—,” O’Keeffe wrote Stieglitz on her last day. “I hate to go—It has been lovely here—quiet—only the excitement of what three people can do in the country— … I have three paintings from here—one big one of white flowers—It has been funny to see the way it made them all open their eyes—and two of the lava with the sea—am sorry that I got no cane.”

On March 20, Willis, Patricia and O’Keeffe drove the road out to reach Central Maui. There O’Keeffe was keen to paint in ‘Ïao Valley, a place she had likened to Yosemite when she first arrived on Maui. It is, she wrote a friend, “a wonderfully beautiful green valley—sheer green mountains rising as straight up as mountains can.” She and Patricia headed for the valley. The narrow winding road frightened O’Keeffe, but she braved it for the landscape. Deep in ‘Ïao, she set up her easel and began to paint. When the rain came in, O’Keeffe and Patricia took shelter in the car. O’Keeffe instructed Patricia to “turn around and sit quietly” and kept painting. Then, no doubt feeling sorry for her young companion, she relented. “I suppose I could let you watch—but absolutely no talking.”

Patricia turned around and watched, fascinated. The image seemed to flow out of the brush effortlessly—before her eyes, she could see the valley appearing on the canvas, with a lone waterfall dropping through the heart of it. She was awed. Then the rain arrived in torrents and O’Keeffe had to stop. The two retreated to the hotel where they were staying, the Maui Grand in Wailuku, and went to their rooms: O’Keeffe to paint and Patricia to read Nancy Drew.

The next morning, O’Keeffe, Willis and Patricia had one last adventure together. They set off in the dark at ten minutes to 4 a.m. hoping to see the sunrise from the summit of Haleakalä. It was not to be—it was cold and cloudy at the summit and the sun was nowhere to be found—but there was some excitement to the visit. O’Keeffe recorded it when she signed the park’s guest book and in the comments section noted “Patricia’s first snow.” When the three were back in Wailuku, O’Keeffe asked Patricia to pick something for herself at the hotel gift shop. Not wanting to select anything expensive, Patricia chose a pair of silk tabis and, urged by O’Keeffe to select something more, a choker made of small Ni‘ihau shells. Then she and her father drove home to Häna, and O’Keeffe drove back to ‘Ïao to paint.

O’Keeffe left Maui on March 24. Before she boarded the steamer Waialeale, which would take her to Hilo, she wrote Stieglitz, “I enjoy this drifting off into space on an island—… I’d as soon stay right here for a couple of months but I seem to have to move on.” She remained on Hawai‘i Island until April 10, returned briefly to O‘ahu and sailed for California on the Matsonia on April 14. Back in New York she was felled by illness—stomach problems, headaches, weight loss. “It wasn’t the islands that did it to me either,” she wrote a friend, “the islands just staved off my having to get into bed before.” She did manage to send the requisite two canvases to Dole—one of a heliconia, the other of a papaya tree in ‘Ïao Valley. Disheartened, company representatives asked if there wasn’t any way they could persuade her to paint a pineapple? They put a whole one, untouched, on a Pan Am Clipper, and thirty-six hours later O’Keeffe was examining it in her studio. “It’s a beautiful plant,” she conceded, “it is made up of long green blades and pineapples grow on top of it. I never knew that.” She painted a sharp, kinetic masterwork titled Pineapple Bud, and soon it was selling pineapple juice across the country.

By the end of the summer, O’Keeffe was well enough to work again. She painted through the fall and into the beginning of winter, and on February 1, 1940—almost exactly a year to the day since her departure for Hawai‘i—she opened an exhibit at Stieglitz’s gallery, An American Place. The show featured twenty canvases with Hawai‘i themes. Seven were landscapes, all from Maui: five from ‘Ïao, two from Häna. Two were of fishhooks and the rest were portraits of her beloved flowers, including a luminous study of angel’s trumpets she and Patricia had discovered along the road in Kïpahulu.

The exhibit earned O’Keeffe raves. In a world already at war or just on the brink, her work was a reminder of the grace and order of the natural world. Stieglitz wrote of the show to a friend, “Many believe it to be a health-giving one to all coming to the place.” O’Keeffe herself wrote, in her statement for the show: “What I have been able to put into form seems infinitesimal compared to the variety of experience. One sees new things rapidly everywhere when everything seems new and different. It has to become a part of one’s world, a part of what one has to speak with—one paints it slowly.”

After O’Keeffe left Häna, Patricia was ready to go, too. She realized, in the void created by O’Keeffe’s departure, that she was lonely in Häna and wanted friends around her. She asked her father if he would send her to boarding school in Honolulu and to her surprise he agreed. On vacations she would go home, a long journey that involved taking a steamer from Honolulu Harbor to Lahaina and then driving across Maui.

In December of 1941 the war came to Hawai‘i and changed everything. Army engineers mined the road to Häna and set explosives around the town’s dock. Willis Jennings was ordered to make sure that things were blown up if he got word that the Japanese were coming. In 1942 he was transferred to the Hakalau sugar plantation on the Big Island after the Häna plantation’s owners decided to start phasing out their operations. San Francisco magnate Paul Fagan then purchased the land and created a cattle ranch and, in 1946, a small hotel.

On May 1, 1941, Patricia got a letter from O’Keeffe. “Oh—I wish that I could go for one of those fine walks with you again—and see you sitting there at the head of the table so young and so dignified,” O’Keeffe wrote. “—I wonder if you wear shoes comfortably once in a while nowadays.”

Hawai‘i, it seems, was never far from O’Keeffe’s mind. “I have always intended to return,” she wrote her friend Ansel Adams. “I often think of that trip at Yosemite [with you] as one of the best things I have done—but Hawaii was another.” She did go back twice, once in the 1950s to Honolulu and again in 1982, at the age of 94, to Häna—a place, she had written Stieglitz forty-three years earlier, “not like other places.”

O’Keeffe’s first visit to Hawai‘i came at a turning point in her life. “Filling a space in a beautiful way,” she said. “That is what art means to me.” On Maui, she filled the space of her days with the smell of the sea and burning cane, ate raw fish and ‘ulu, wore thongs of grass and wood. (“It hurt at first but I get on very well now.”) The promises of newness, challenge and autonomy that had hung in the air at Grand Central Station—O’Keeffe found them all. A year after she returned to the United States, in 1940, she bought a house at Ghost Ranch, north of Abiquiu, in New Mexico. After Stieglitz died in 1946, she settled his estate and moved to New Mexico permanently. There in the wilderness and isolation she continued to paint, and she remained in New Mexico until her death at the age of 98.

Patricia Jennings married twice and had five children, nine grandchildren and three great-grandchildren. Today, at 85, she lives in Waimea, and she has just written a memoir of her time with O’Keeffe, Coming Into Bloom, which is part of a new book just out from Koa Books, Georgia O’Keeffe’s Hawai‘i; the book also includes O’Keeffe’s letters to Stieglitz from Maui and the twenty paintings she made of the Islands.

“She was a fine person, and she certainly changed my life at that time,” says Patricia today. “I realized that it is important to be the individual you are. She treated me like a person instead of a child, and she seemed to respect my opinions on things. I rather think she must have because she was pretty frank and pretty discerning. I suppose I was, too.”

Seven decades after they met, Patricia remains grateful to O’Keeffe for all of the influences the artist has had on her life, big and small—everything from her decision to have a large family to the markings she makes when she writes. “To this day,” she recalls with a laugh, “I can remember somehow we were talking about punctuation, and Georgia said, ‘I find the dash very useful, I don’t worry about those other punctuation things.’ I remember thinking at the time, ‘What a good idea’—and I still use them.”