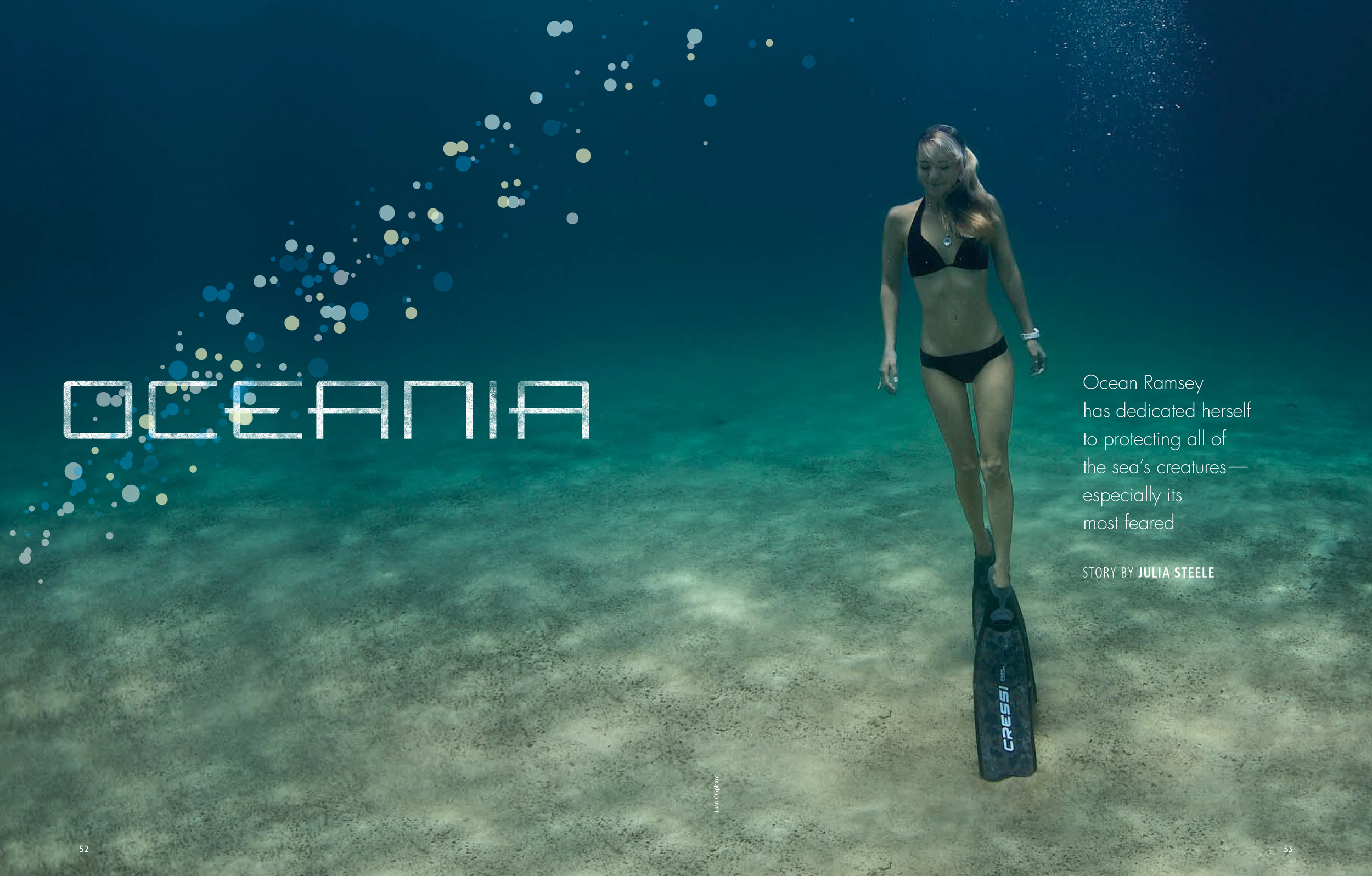

Late 2012. Far off the Baja Coast of Mexico, Ocean Ramsey is on a research ship in an area where great white sharks are known to gather. The svelte 27-year-old dive instructor from O‘ahu is here for the third time, drawn back once again by her guiding passion: to understand and protect sharks. Ramsey has swum in the wild around the world with more than thirty species—tiger sharks in Hawai‘i, bull sharks in Fiji, silver tips in Tahiti, angel sharks in California—but on this trip she will have an experience she’s never had before: freediving with great whites.

Ramsey is with a boatload of colleagues, all of them here to gather data on great whites. The ship they’re on has two observation cages at its stern: divers sit in the cages, either on the ocean surface or in the water column below it, breathing from scuba tanks. They sit sometimes for hours waiting for the sharks to appear, then watching them once they’ve arrived. They take pictures of specific markings, gathering information for an identification book that is tracking as many individual great whites as possible.

When the divers can see that the sharks are relaxed and not displaying any signs of concern—for example, popping gills or dropping pectoral fins—they occasionally leave the cages and swim out to the animals. They take pictures and videos of themselves swimming alongside the creatures. These pictures, they know, have the power to subvert perception: Show someone a picture of a great white swimming solo, and that person will in all likelihood see a threatening predator. Now show a picture of a great white and a diver swimming peacefully together, and that person is bound to rethink things.

On this day Ramsey is in a cage at the surface. Three to four great whites swim around her, and she reads their behavior, focusing on finding the shark that is most relaxed. She settles on a large female, takes a deep breath, opens the cage and glides down into the deep blue. She wears a wetsuit, fins and a mask, nothing else.

“I am easing close, and I notice the shark kind of slows down,” she remembers of what happened next. “I reach my hand to the top of her head, and she accepts my touch, so I slide my hand back to the base of the dorsal fin.” Without the bubbles and noise that come from a scuba tank, Ramsey is able to get even closer to the shark. She has chosen not to wear gloves so that her skin will touch the animal’s. When she looks into the its eye, the shark acknowledges her. “It was such a beautiful, rare thing,” she recalls later. “In an encounter like that, your heart stops rather than races.” The shark swims through crystal-clear water, calmly pulling Ramsey along until she lets go of the shark’s dorsal fin and swims to the surface. That day the intrepid freediver rides on the backs of other great whites, too, and over the course of the trip freedives with seven of the sharks.

Hundreds of thousands of people have now watched her do it. Driven by their zeal to let the world know that sharks are not the monsters they’ve been made out to be, Ramsey and her colleagues at Waterinspired.com posted a three-minute compilation video of those dives to YouTube, where it quickly went viral. It shows a graceful woman with a long blond braid undulating through the sea alongside large and powerful sharks, each moving with an extraordinary efficiency born of four hundred million years of evolution. As a piece of filmmaking, think of it as the anti-Jaws.

“Why did I get into shark-diving? It’s the way I grew up. It feels predestined and it fits,” Ramsey says, reeling off her major influences: a father who was an avid diver in his hometown of San Diego, a mother from Hawai‘i who taught her to respect all forms of life, four rough-and-tumble brothers and a sister, college coursework in marine biology and most of all an upbringing in both Hawai‘i and San Diego that put her in the water just about every day and made her curious and joyful. “I never took swim classes, but I remember being on my dad’s shoulders, wading out to the shorebreak,” says Ramsey of her earliest times in the ocean. “My dad would be like, ‘Go to the bottom and crawl your way out.’ I was curious and I would look around underwater.” She had her first personal encounter with a shark—a small reef species she spotted cruising beneath her surfboard—when she was 13. “I saw this slim shape. It didn’t seem threatening, so I paddled after it. It was uninterested in me. I watched it through the water clear as glass, and I was enamored with it,” she recalls. She learned to scuba dive when she was 15, and by the time she was 18 she’d become a certified PADI instructor. She took off to spots around the world to teach diving and to surf—Fiji, Australia, Indonesia, French Polynesia, the Caribbean—and everywhere she went she learned more about sharks, watching them in the water, growing ever more comfortable with them, observing them enough to be able to discern individual behaviors and temperaments.

At the same time she was learning more about the realities that sharks face in the twenty-first century. An average of three sharks are killed every second, she notes, and a number of shark species including great whites are now endangered. That might come as welcome news to those who think of sharks as nothing more than a menace to humans, but sharks, Ramsey notes, are apex predators that are crucial to the marine and even the global ecosystem. As an example she cites a recent study that shows there are now fewer than 350 great whites left in the triangle between California, Mexico and Hawai‘i. With their decline along the California coast has come a boom in seal populations. “And the seals eat the same fish that we do,” says Ramsey, “so fish prices go up for us, and fish populations are being decimated. Those fish feed on other things, and if they’re not there then the balance of the ocean gets thrown off all the way down to the kelp forests—which we need to help create the air that we breathe.”

Ramsey studied marine biology at the University of Hawai‘i at Mänoa and at San Diego State University, where she got her bachelor’s degree. She is now working toward a master’s in ethology—the study of animal behavior and psychology. She still gets in the water every day, taking scuba divers out into O‘ahu waters and occasionally assisting on research dives. She is working with shark experts from Australia and New Zealand on a book about the animals—she’ll contribute the chapter on behavior, based on her studies and years of real-world experience. Her message? Sharks are profoundly misunderstood and maligned. “We believe shark attacks are cases of mistaken identity, “ she says. “Attacks are very, very rare because we are not a natural prey item for them, and sharks have far more sensory systems than we do—they sense us before they see us.” If visibility is low or a shark is curious, it might come closer, but if it actually bites, that, says Ramsey, is fundamentally because the shark is confused, not because it is aggressive. She notes how often people greet this news with relief when she takes them out diving. “People don’t want to be afraid when they get in the water,” she says. “It’s liberating for them to let that go.” Liberating perhaps, but she is certainly not encouraging others to follow in her wake. “No, no, no! These are not puppies,” she says emphatically of sharks. “I do this because everything in my life has directed me to do this.”

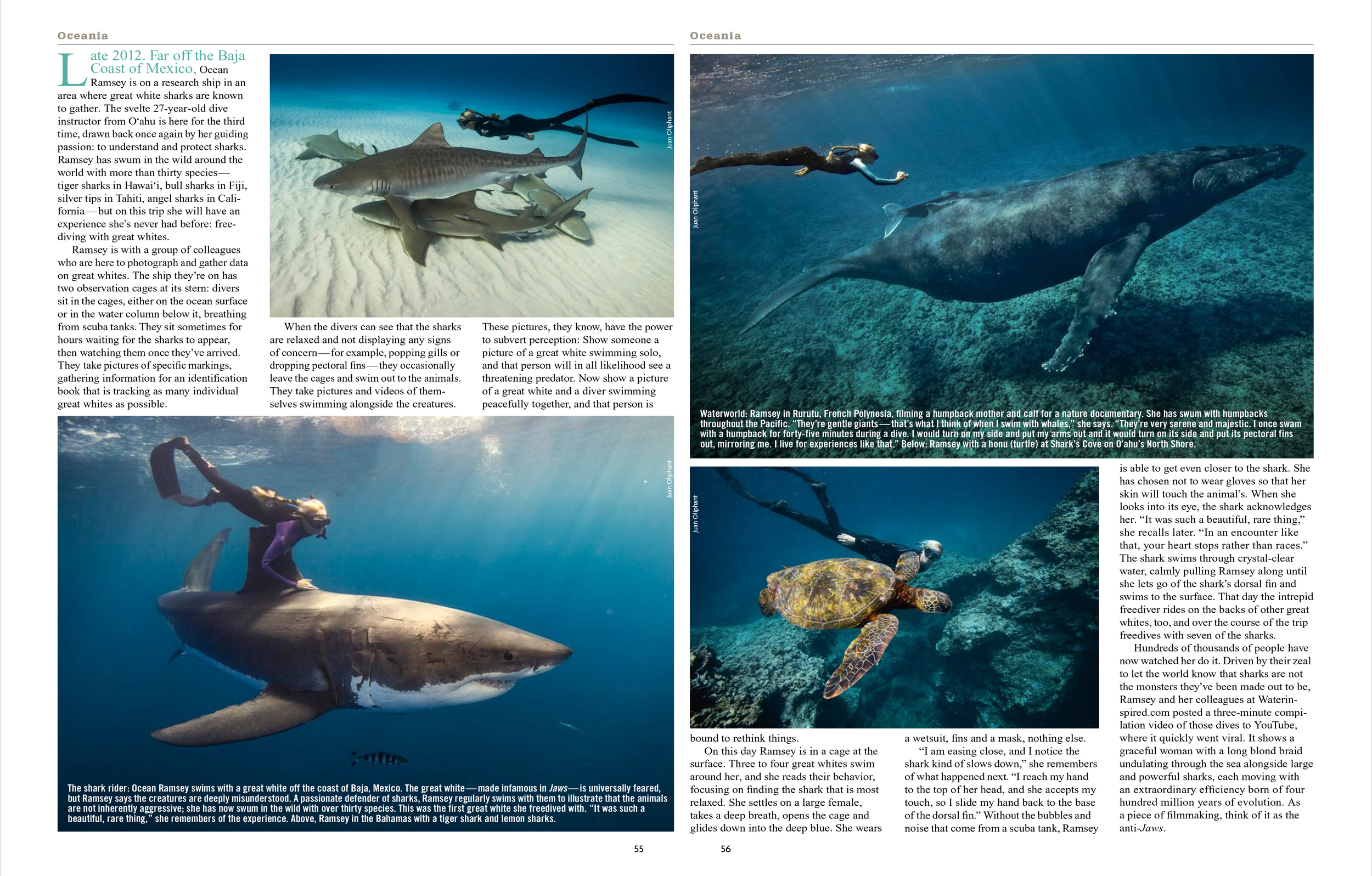

Ramsey has trained herself to hold her breath for six minutes and nineteen seconds, the skill that enables her to freedive with sharks the way that she does. Holding her breath that long necessitates staying calm—which is also important because sharks can sense a person’s heart rate. But while her shark diving may be all about communing with nature, there is one part of Ramsey’s life where she will happily admit to loving an adrenaline rush or two: her stunt work. It, like almost everything in her life, arose from her bond to the ocean. In her early 20s she was working as a dive instructor on the O‘ahu set of the movie Into the Blue 2: The Reef, and neither the film’s leading lady nor her stunt double could execute a complex underwater stunt in one take. The director was about to break up the stunt into two parts when a colleague of Ramsey’s volunteered that Ramsey would be able to do it all in one breath. She was a hit and has gone on to do numerous stunts on TV and in movies (among them Hawaii Five-0, Off the Map and Captain America: The First Avenger). She’s a trained stunt driver, can do jumps and falls, can execute wipeouts on dirt bikes, but most of her stunts happen in the arena that gave her her name: the ocean. She’s in the Screen Actors Guild union. “It’s a job,” she says, “and I like I a lot. It pays well, and it’s fun and active.

“Shark diving is so different from stunt work. It’s like they’re not even in the same neural pathways. Freediving with sharks you have to keep your heart rate low; you’re relaxed and peaceful. Doing stunts is like being at the gym, a workout. It’s a performance.”

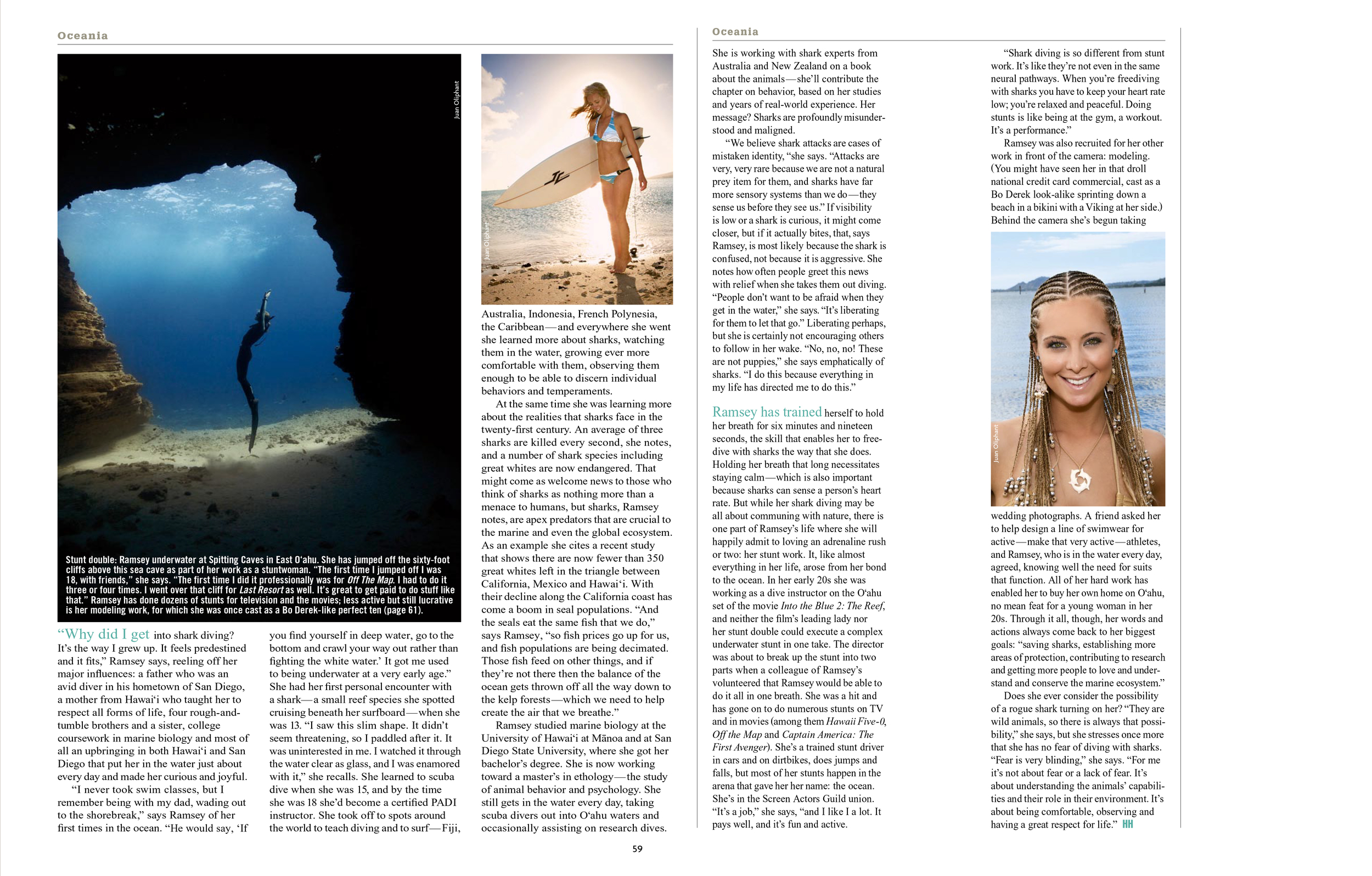

Ramsey was also recruited for her other work in front of the camera: modeling. (You might have seen her in that droll national credit card commercial, cast as a Bo Derek look-alike sprinting down a beach in a bikini with a Viking at her side.) Behind the camera she’s begun taking wedding photographs. A friend asked her to help design a line of swimwear for active—make that very active—athletes, and Ramsey, who is in the water every day, agreed, knowing well the need for suits that function. All of her hard work has enabled her to buy her own home on O‘ahu, no mean feat for a young woman in her 20s. Through it all, though, her words and actions always come back to her biggest goals: “saving sharks, establishing more areas of protection, contributing to research and getting more people to love and understand and conserve the marine ecosystem.”

Does she ever consider the possibility of a rogue shark turning on her? “They are wild animals, so there is always that possibility,” she says, but stresses once more that she has no fear of diving with sharks. “Fear is very blinding,” she says. “For me it’s not about fear or a lack of fear. It’s about understanding the animals’ capabilities and their role in their environment. It’s about being comfortable, observing and having a great respect for life.”