In 1950 the tallest building in Honolulu was the 184-foot Aloha Tower, and the annual visitor count to the Islands was 46,593. By 1970, high-rises had mushroomed across the city skyline, and the annual visitor count had skyrocketed to 1,746,970. The massive boom that Honolulu witnessed in the two decades between the start of the Korean War and the breakup of the Beatles brought thousands of new buildings to the city, all at a time when Modernism—with its rational and efficient use of space, emphasis on form and focus on structure and materials—was emerging across the world as the movement of the day. “Honolulu was essentially made when Modernism was the dominant architecture,” says local architect Louis Fung. The best architects working in the city at the time—among them the Russian immigrant Vladimir Ossipoff, the MIT-trained Frank Haines and Taliesin West veteran Stephen Oyakawa—sought to blend Modernism with a specifically Hawaiian sensibility. The architects incorporated organic materials like lava rock and sandstone to preserve the feeling of the land within the sleek lines of their buildings. They used wide overhangs, courtyards, large lānai and pocket doors to open streamlined structures up to the natural world. They used neutral colors to give first billing to the vibrant hues of Island flora. They sited for view planes that took full advantage of the dramatic juxtaposition of mountain and sea. And, driven by a devotion to natural light, they utilized the oldest guiding architectural design principle in the world: The sun rises in the east and sets in the west. But there were indications that design attuned to the Island environment might not last. Even by the mid-1960s, Honolulu’s architects were concerned about what was coming next. “Honolulu is a city in the sun,” noted a group of city architects in 1966, “cooled by the trade winds, softened by the shadows of the clouds and mountains, the greenery, and most important, the texture of the buildings themselves. … The challenge is to understand and retain the most basic and meaningful element of this character at a time when we are building larger buildings, artificially lighted and air-conditioned working places, increasingly dense development of land, and utilizing modern materials and methods of construction. All of these elements, which are becoming more and more a part of our contemporary life, are the very ones which can tend to destroy our character if this challenge is not forcefully met through the design of our buildings.” The twelve buildings on these pages give a sense of the best architecture that was created in Honolulu in the midcentury—architecture that was inventive, dynamic and at ease with its surroundings.

Text for spread two above:

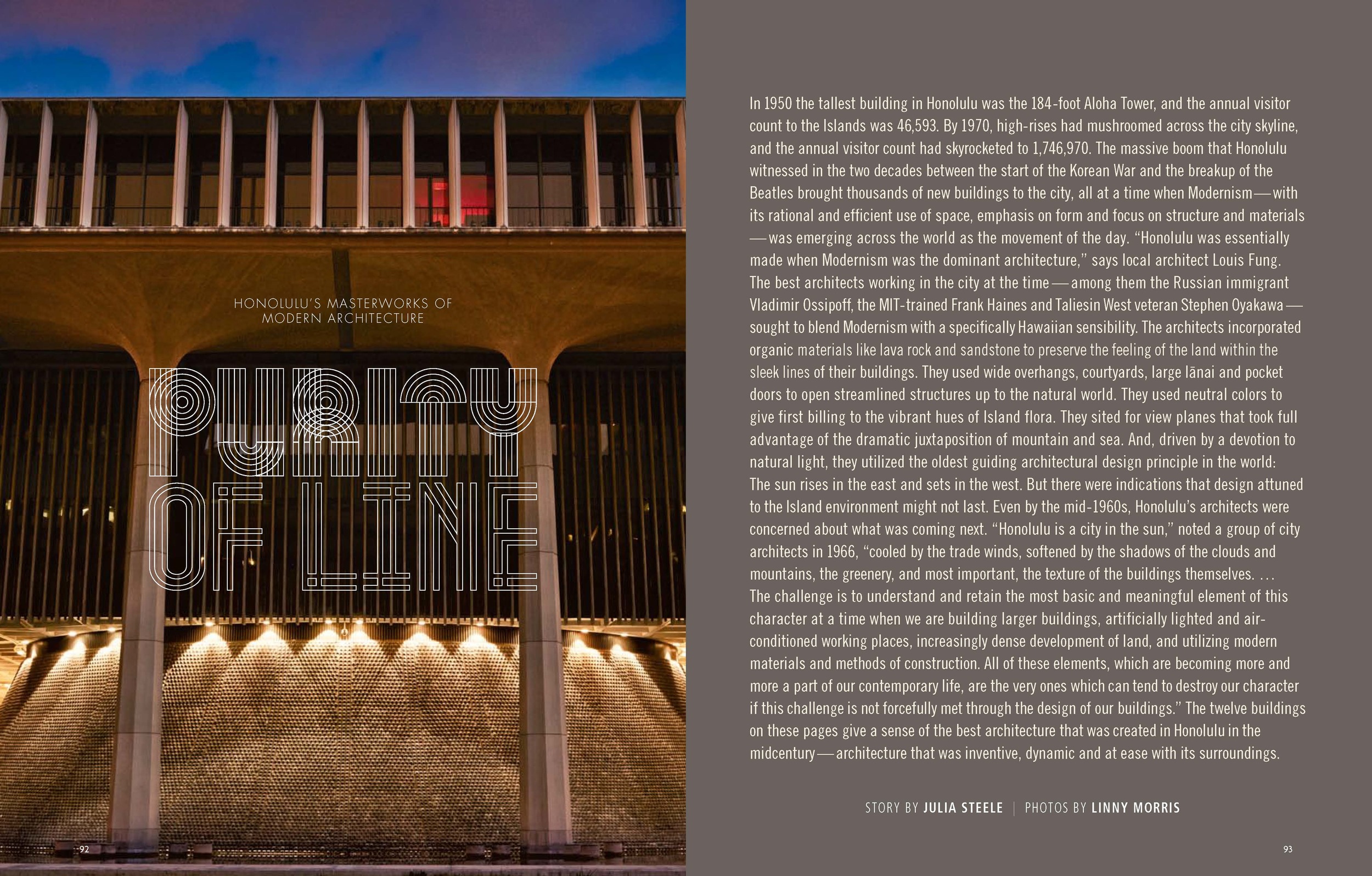

New civic buildings appeared across Honolulu as government money poured forth for projects. Thomas Jefferson Hall (facing page) was created in 1963 by one of the great architects of the twentieth century, I.M. Pei; Pei used concrete and steel to dramatic effect to create a deeply cantilevered roofline and give the building a monumental feel and scale that was distinctly modern. Jefferson was one of four buildings Pei designed for Honolulu’s then-newly created East-West Center; Frank Haines remembers several dinners with Pei at the Halekulani Hotel while Pei was working on the project. “He was absolutely happy with the way it turned out,” says Haines. Right next door to the EWC, the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa saw the creation of two of its landmark buildings during this period. The first, Bachman Hall (middle left), was completed in 1949, the first postwar building created on campus. It is celebrated for its clean lines, expansive entryways and large, light-filled courtyard, as well as its two murals by famed modern artist Jean Charlot. Bachman’s openness to the natural world was shared by Sinclair Library (bottom left), which opened in 1956 with space for six hundred thousand books and—unthinkable today—no air conditioning. Sinclair’s organic feel is enhanced by its graceful curved entry, accented with Wai‘anae sandstone, as well as its numerous louvers and large windows, which welcome in natural light and tradewinds. “We were directed to create a building that was adapted to the local climate,” recalls Haines, who worked on Sinclair. “It was great for students and great for insects, too.” Sinclair opened in 1956; a decade later it was followed by Liliha Library (top left), designed by Stephen Oyakawa, a Hawai‘i architect who’d worked alongside Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West.

Text for spread three above:

Perhaps the most admired of the financial buildings created in Honolulu during the mid-century is the 1962 IBM Building (top right), which was designed by Vladimir Ossipoff. Its celebrated grille-work pulls off three feats at once: It shades and cools the building naturally, creates ever-changing shadows and evokes the world of IBM itself with its computer-like patterning. “Magnificent,” says Frank Haines, noting that recent plans to demolish the building were derailed by public outcry. The 1958 Board of Water Supply building (middle right) fuses the horizontal lines and reinforced concrete of Modernism with numerous other influences: The design on the building’s aluminum grille-work comes from the Forbidden City in Beijing, the canopy over its front entrance is modeled after a Japanese torii gate and the ‘ōlelo no‘eau on the fountain is Hawaiian: Uwē ka lani, ola ka honua (When the sky weeps, the earth lives). The Occidental Life Insurance Building (bottom right) is an oddity for its times. The main building was completed in 1951, but the cantilevered office that everyone remembers it for was not erected until the mid-’60s. Haines worked on both the original and the add-on; he calls the first “fine,” the second “gross.” The Financial Plaza of the Pacific (facing page) pushed Honolulu architecture into Brutalism, which, with its raw concrete and masculine forms, Louis Fung calls “the heart and soul of Modernism.” The Plaza, completed in 1968, houses three structures: a twenty-one-story high-rise, a twelve-story high-rise and a six-story bank building with a concrete overhang worthy of the Soviet bloc. Architect Leo Wou gave all three over-scaled features and sandblasted surfaces. One of its pluses: 43 percent of the city block it sits in is allocated for open space. “Going up,” points out Haines, “allows for more open space on the ground.”

Text for spread four above:

As the city grew, buildings sprang up everywhere. Modernist architecture could be seen, says Louis Fung, in the workforce housing appearing all over Waikīkī and Mō‘ili‘ili: Industrial Style three-story walkups that had, he says, “powerful strokes and included intricate details, like screens, signs and lava rock.” The zigzag thin-concrete roof of the Punahou Circle foyer (facing page) typifies architectural accents of the day; early high-rise apartment buildings also had länai, natural ventilation and what architect Sid Snyder calls “a more Hawaiian quality.” Snyder was Ossipoff’s partner, and both the Pacific Club (bottom right) and Thurston Chapel (top right) are Ossipoff buildings. Ossipoff gave the Pacific Club the feel of a grand yet intimate residence in which the outdoor and indoor spaces flowed so seamlessly that it was hard to tell which was which. Thurston Chapel, on the Punahou campus, abuts a lily pond; sunlight reflecting off the water casts ever-changing shadows through the chapel’s stained-glass windows. “It’s typical,” says Snyder, “of the Ossipoff characteristic: pretty definitely Modern, very aware of where it is and unique.” “I go to a lot of funerals there,” says Haines, who is now 93. “It’s a wonderful building.” The State Capitol (middle right and opening image) was the largest architectural undertaking of all in this era. It took three years to build, cost $24.5 million and opened in 1969 as one of the country’s most unconventional state capitol buildings. Within its 558,000 square feet, it evokes numerous elements of the Islands: reflecting pools that represent the ocean, forty columns that suggest royal palms, cone-shaped legislative chambers that symbolize volcanoes and a huge courtyard designed to invite in nature and the people. “I’m very proud of it,” says Haines, who was involved in its creation. “It’s right in both form and function.”