Mayumi Oda appears in her driveway like an apparition, all in white—long white shirt, long white skirt—in the darkness of the late night. She’s slight but strong and completely self-possessed. Immediately she takes charge (“Park here. Follow me. Watch your step. Meet my brother.”), and within minutes I’m at her kitchen table with a hot cup of roasted twig tea, a bowl of apple bananas from her garden and the most beautiful sugar I have ever seen—ornate, leaf-embossed crystal cubes from Japan.

“You’ll sleep in the yurt,” Mayumi tells me as we drink tea, “and in the morning you’ll meet the others who are here now: a student of mine from Japan, her boyfriend who’s building me a pond, a young Russian woman, an African-American woman who’s a costumer in New York, my son and his girlfriend, a man from Africa who comes to work in the garden and a Chilean who sleeps in his truck.” She laughs, more at herself than anything. “It’s a full house,” she says, and she grabs a flashlight to lead me out onto the land. We walk through thick, vog-laced air filled with the sounds of crickets, dogs and coqui frogs and come to the yurt, which is vast and spartan, a giant circular dome with a lone sleeping bag lying in the middle of the floor like a life raft. Mayumi hands me the flashlight and wishes me goodnight, and I crawl into the bag and fall asleep.

In the morning Mayumi tells me about her life. Some of it I know: Acclaimed artist hailed as “the Matisse of Japan” and famed for her vivid paintings. Ardent activist who led the battle against Japan’s plans to ship plutonium across the Pacific Ocean. Devout Buddhist who illustrated four of Thich Nhat Hanh’s books. Passionate farmer who discovered her essence in the same soil that nurtured her crops and detailed that experience in her autobiography I Opened the Gate, Laughing. Now she lives on a five-acre farm just south of Kona, in Kealakekua. “But did you know that today there is an ‘a’ missing in the name?” she asks. “In reality, this area is ‘Ke ala ke akua’—a phrase that means ‘The path of the gods.’”

We are in the kitchen as we talk. Mayumi and others are expertly chopping daikon greens and making a huge pot of fish broth. There is kabocha pumpkin from the garden too and fresh mint and lemongrass for tea. Now that I see the house in the light, it’s clear how thoroughly it is given over to the land: There are walls but somehow there’s no division between inside and outside. Insects and lizards come and go, fruits and vegetables lie on either side of the door, ripening or decomposing. Lines blur in this place. There is the process of creation and the creation: There are Mayumi’s paintings of cabbages and there are cabbages; there are her portraits of goddesses and there are flesh-and-blood women who seem to inhabit the same energies as the women on the canvasses that fill the walls.

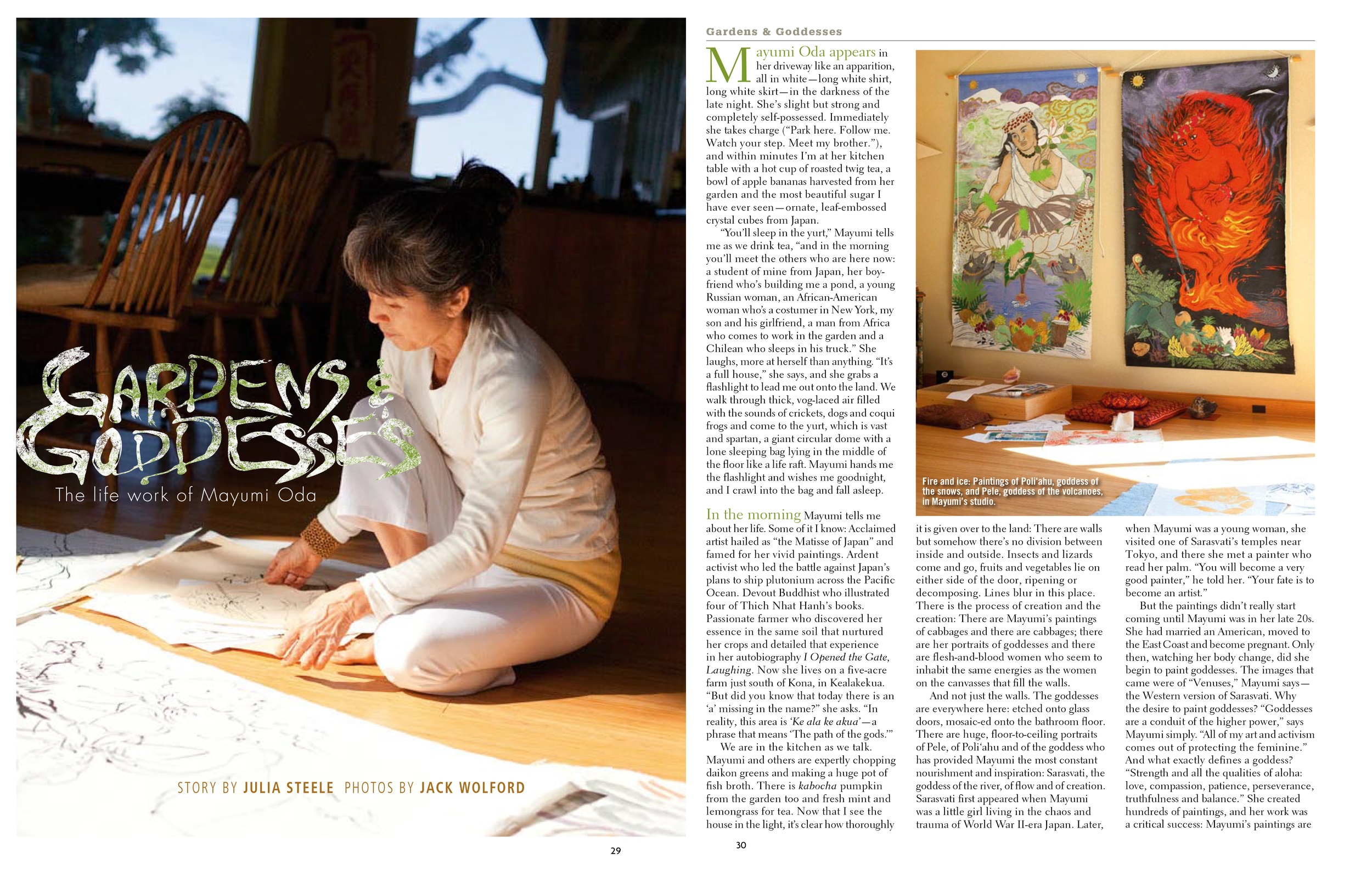

And not just the walls. The goddesses are everywhere here: etched onto glass doors, mosaic-ed onto the bathroom floor. There are huge, floor-to-ceiling portraits of Pele, of Poliahu and of the goddess who has provided Mayumi the most constant nourishment and inspiration: Sarasvati, the goddess of the river, of flow and of creation. Sarasvati first appeared when Mayumi was a little girl living in the chaos and trauma of World War II-era Japan. Later, when Mayumi was a young woman, she visited one of Sarasvati’s temples near Tokyo, and there she met a painter who read her palm. “You will become a very good painter,” he told her. “Your fate is to become an artist.”

But the paintings didn’t really start coming until Mayumi was in her late 20s. She had married an American, moved to the East Coast and become pregnant. Only then, watching her body change, did she begin to paint goddesses. The images that came were of “Venuses,” Mayumi says—the Western version of Sarasvati. Why the desire to paint goddesses? “Goddesses are a conduit of the higher power,” says Mayumi simply. “All of my art and activism comes out of protecting the feminine.” And what exactly defines a goddess? “Strength and all the qualities of aloha: love, compassion, patience, perseverance, truthfulness and balance.” She created hundreds of paintings, and her work was a critical success: Mayumi’s paintings are now in the permanent collections of the Library of Congress, New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

In her late 30s, Mayumi divorced and moved to California to paint, work on a farm and immerse herself in the Buddhism she’d touched as a child. At 50, she turned to anti-nuclear activism. After a decade of that life, she moved to the Islands. She’d first come to Hawai‘i in the ’80s to paint for a semester at the East-West Center; years later, returning from Tahiti after an anti-nuclear protest, she decided to move to the Big Island. She began by leasing three acres on the road that descends to Pu‘uhonua o Hönaunau (“I always wanted to live in that area,” Mayumi says. “It was where ‘Iolani Luahine [a revered kumu hula] had a house. Her spirit always called me.”) In 2000, she bought the place she’s in today, Ginger Hill, and began her next phase as an artist, creating paintings, of course, but also other works: meals, groves of banana trees, a community.

There are three centers of inventiveness at her farm—the garden, the kitchen, the art studio. She regularly invites women—mostly young Japanese women—to Ginger Hill for what she calls “goddess training.” It’s an idea that traces back a long way: As a girl in Japan, often hungry because of the war, her one solace was her grandmother’s garden, where she felt the calm and certainty that nature (“the mother,” in her words) would protect and provide for her. She invites women to come to the farm for a good block of time (three months or so) to eat healthy food, work on the body, work in the garden, clear away obstacles and learn to live happily. “That sense of oneness, that the mother will always give you sustenance—that’s what I’m really trying to convey,” she says. “People take whatever they need to take. This place is very forgiving in the sense of allowing people to be who they are.”

Mayumi’s garden at her farm in Kealakekua is laid out not in rows but in a circle—a tribute to the flow of Mayumi’s archetype, Sarasvati. The garden is prolific and flourishing, filled with kale, brussels sprouts, beets, eggplant, sugarcane, tapioca, papaya, taro and numerous other plants. “Happiness,” Mayumi says at one point as she fills a tub with fresh purple beans, “is harvesting a bucketful of vegetables.” As she plucks pods from the bushes, she remembers a picture she drew when she was a girl of 5 in Japan: a picture of a little girl standing in a lush garden wearing a beautiful kimono and holding a basket of vegetables. Mayumi’s aunt—somehow prescient enough to recognize that her niece was drawing a portrait of the life she would create—kept the picture and still has it six decades later. “The fundamentals don’t change,” Mayumi says now. “These are the pieces of your life that are very important, very powerful.” She still has the accent of her homeland and “very” leaves her lips sounding like “fairy.” She holds her bucket of beans under her arm, surveys her garden with a loving smile and turns to walk back up the hill to her house.