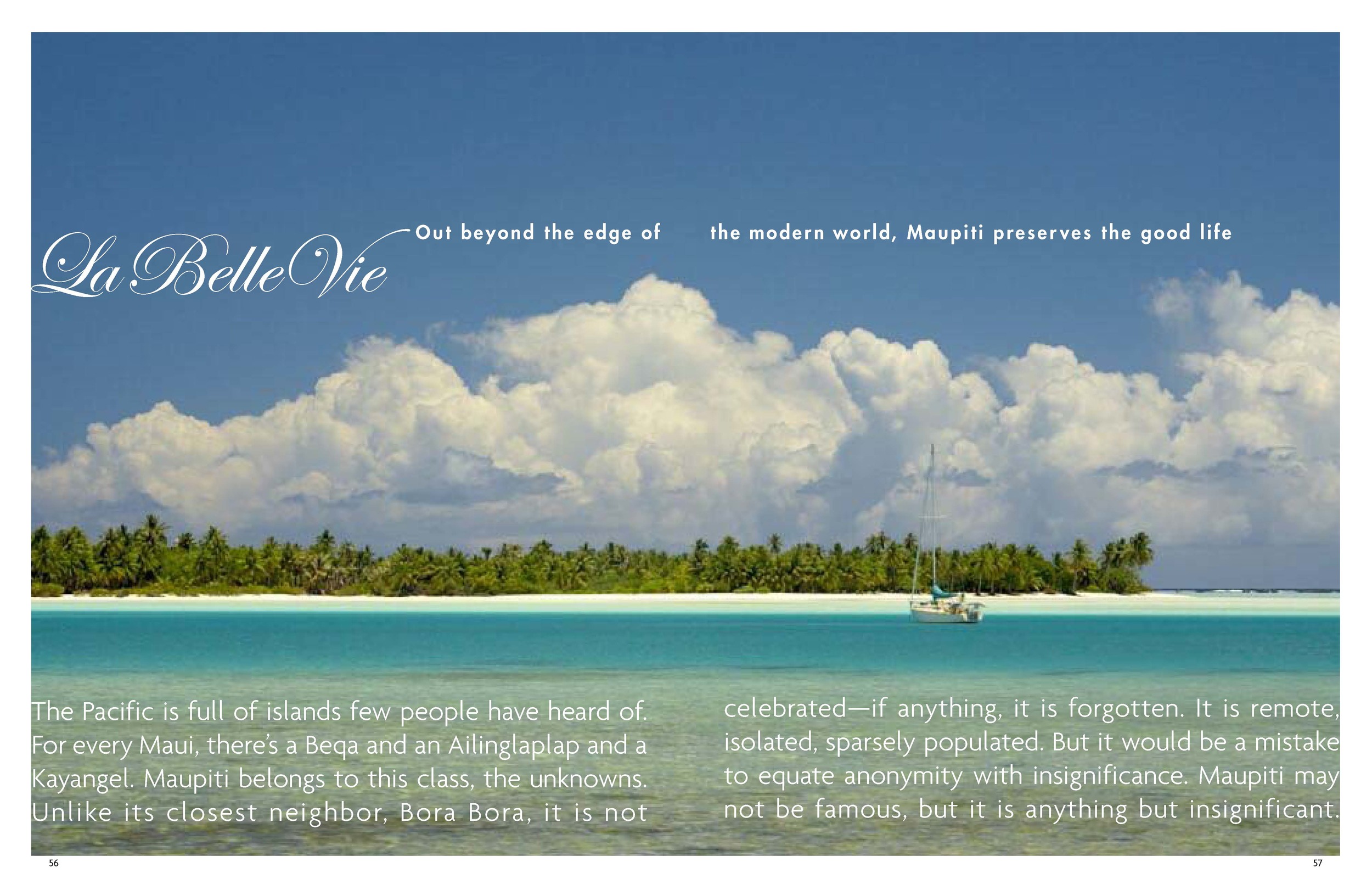

The Pacific is full of islands few people have heard of. For every Maui, there’s a Beqa and an Ailinglaplap and a Kayangel. Maupiti belongs to this class, the unknowns. Unlike its closest neighbor, Bora Bora, it is not celebrated—if anything, it is forgotten. It is remote, isolated, sparsely populated. But it would be a mistake to equate anonymity with insignificance. Maupiti may not be famous, but it is anything but insignificant.

I got my first clue of that fact the night before I left for the island. I’d telephoned Dr. Yoshi Sinoto, the Pacific’s foremost archaeologist, a man who four decades ago did work on Maupiti. When I mention the island’s name on the phone, he begins to tell me astonishing stories of his time there: of a boat wreck, drownings and elderly women all possessed by the same dream; of a frame-up, thefts and midnight interrogations by Bora Bora gendarmes. They are tales of intrigue and discovery that conjure up adventure on a grand scale. The best part Sinoto tells me last, of The Great Maupiti Find, a 1,200-year-old site stumbled on by a watermelon farmer out planting seeds. Sinoto excavated the site and documented its most valuable treasure, a whale tooth pendant from New Zealand—a type of pendant never before seen outside New Zealand. It was the first definitive proof that the Tahitians went West or the Maori came East or both. It was proof that Maupiti is a place where truth lies waiting to be discovered.

Passing through French Polynesia, I get the same two reactions time and again when I tell people I’m bound for a week in Maupiti: envy from those who long for escape, alarm from those who fear boredom. In the French Polynesian consciousness, Maupiti seems to function as some sort of elderly relative: once strong and illustrious, now frail and behind-the-times. Step off the plane and this image of decrepitude vanishes. Maupiti is the oldest island in the Society chain but its current isolation makes it feel the youngest. Immediately you know: There is a wildness here and a languor that has not been co-opted.

The airport alone makes you feel it: There is no floor. A runway, yes (an unnervingly short one that juts into the lagoon) but no floor, just coral. And that is only the beginning. Maupiti lives just to the edge of modernity, flirting with it, skirting it. There is, for example, no hotel. There have been many attempts. The last was a thirty-room, five-star eco-resort. The mayor was solidly behind that plan. He spoke with every family on the island, and the consensus was positive. “Great idea,” he heard again and again. The hotel went to an island-wide vote and failed to pass. The mayor gave up in frustration, the status quo triumphed, and for now, when you stay in Maupiti, you stay at one of the island’s dozen or so family-run pensions. They are small and usually right on the beach; if you are after an immersion into Polynesian living, you could not do better. When I awoke in a little bungalow at Pension Papahani on my first morning—under a mosquito net, listening to the birds and the waves, watching pink light grow gold—it was with the conviction that now I was truly in the Pacific.

Pension Papahani sits on the shores of motu Tiapaa, facing the lagoon. Maupiti’s terrain combines a classic high volcanic island (imagine Moorea) and a number of motus, or small islands (imagine Rangiroa). It is the best of both worlds: In Maupiti’s center sits the high island, lush, dominated by a massive rock mountain, surrounded by the lagoon. The motus, flat, laden with coconut trees, encircle the lagoon; beyond them is the wide-open sea.

Before the advent of airplanes, to get in and out of this island was not easy. There is one and only one pass into Maupiti’s lagoon, a stretch of water notorious as one of the most treacherous passes in French Polynesia. From the beach at Pension Papahani, you can watch the waves smash in the channel. The matriarch of Pension Papahani, Vilna Tuheiava, gave me the most beautiful explanation for this geographic configuration. “Maupiti, c’est une femme,” she told me, “L’île, ca c’est la flanc, the womb. Et la passe, ca c’est la sexe.” In other words, Maupiti is a woman and every time you enter—mythologically at least—you join yourself with her. The Tahitian name of the pass, Vilna told me, is Onoiau, which translates roughly as “you may enter if I allow.” Vilna’s explanation was, I thought, pure Polynesian, straight from a worldview that sees land as a living being, a creature of sensuality and fecundity.

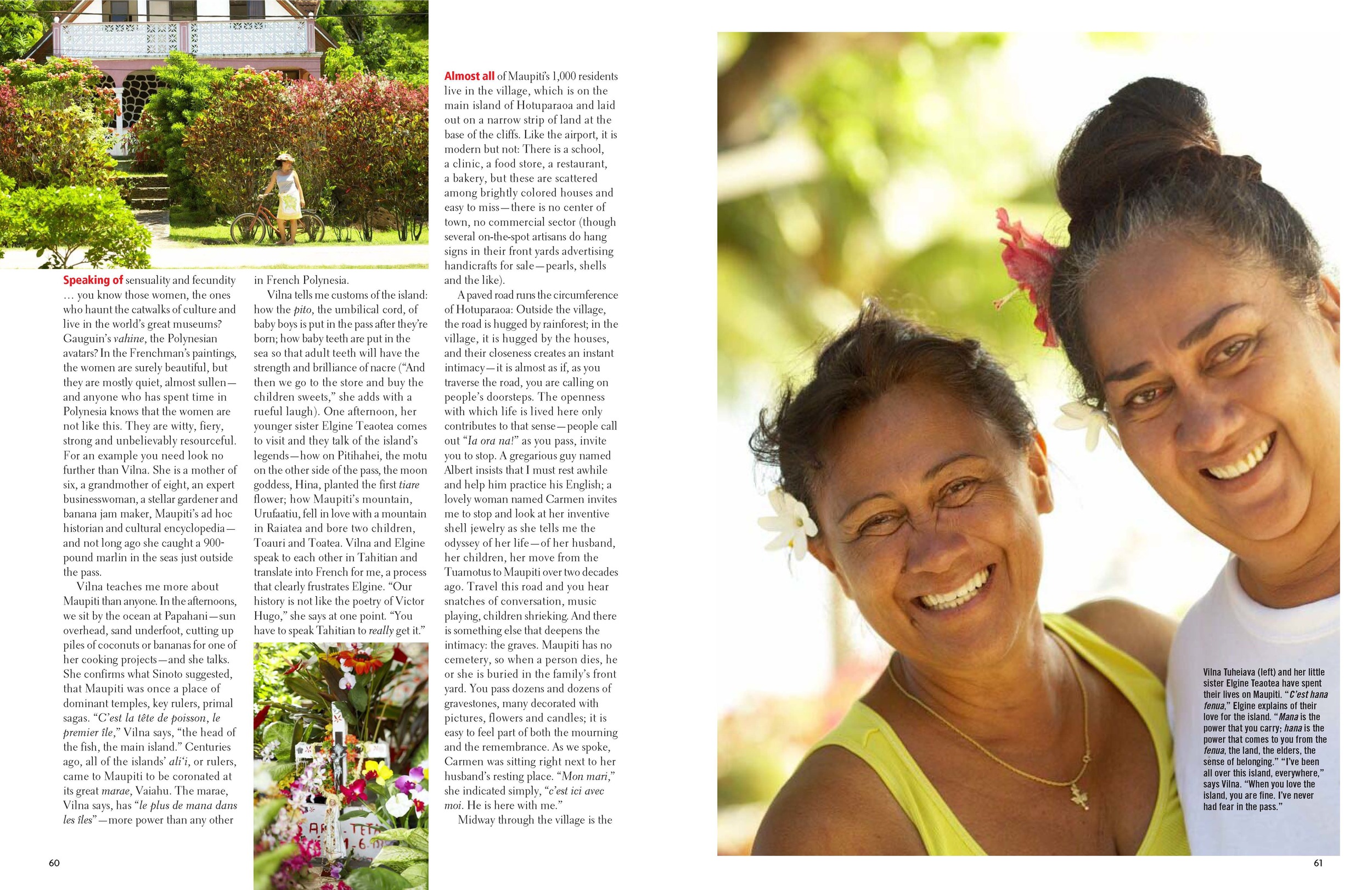

Speaking of sensuality and fecundity … you know those women, the ones who haunt the catwalks of culture and live in the world’s great museums? Gauguin’s vahines, the Polynesian avatars? In the Frenchman’s paintings, the women are surely beautiful, but they are mostly quiet, almost sullen—and anyone who has spent time in Polynesia knows that the women are not like this. They are witty, fiery, strong and unbelievably resourceful. For an example you need look no further than Vilna. She is a mother of six, a grandmother of eight, an expert businesswoman, a stellar gardener and banana jam maker, Maupiti’s ad hoc historian and cultural encyclopedia—and not long ago she caught a 900-pound marlin in the seas just outside the pass.

Vilna teaches me more about Maupiti than anyone. In the afternoons, we sit by the ocean at Papahani—sun overhead, sand underfoot, cutting up piles of coconuts or bananas for one of her cooking projects—and she talks. She confirms what Sinoto suggested, that Maupiti was once a place of dominant temples, key rulers, primal sagas. “C’est la tete de poisson, le premier île,” Vilna says, “the head of the fish, the main island.” Centuries ago, all of the islands’ ali‘i, or rulers, came to Maupiti to be coronated at its great marae, Vaiahu. The marae, Vilna says, has “le plus de mana dans les îles”—more power than any other in French Polynesia.

Vilna tells me customs of the island: how the pito, the umbilical cord, of baby boys is put in the pass after they’re born; how baby teeth are put in the sea so that adult teeth will have the strength and brilliance of nacre (“And then we go to the store and buy the children sweets,” she adds with a rueful laugh). One afternoon, her younger sister Elgine Teaotea comes to visit and they talk of the island’s legends—how on Pitihahei, the motu on the other side of the pass, the moon goddess, Hina, planted the first tiare flower; how Maupiti’s mountain, Urufaatiu, fell in love with a mountain in Raiatea and bore two children, Toauri and Toatea. Vilna and Elgine speak to each other in Tahitian and translate into French for me, a process that clearly frustrates Elgine. “Our history is not like the poetry of Victor Hugo,” she says at one point. “You have to speak Tahitian to really get it.”

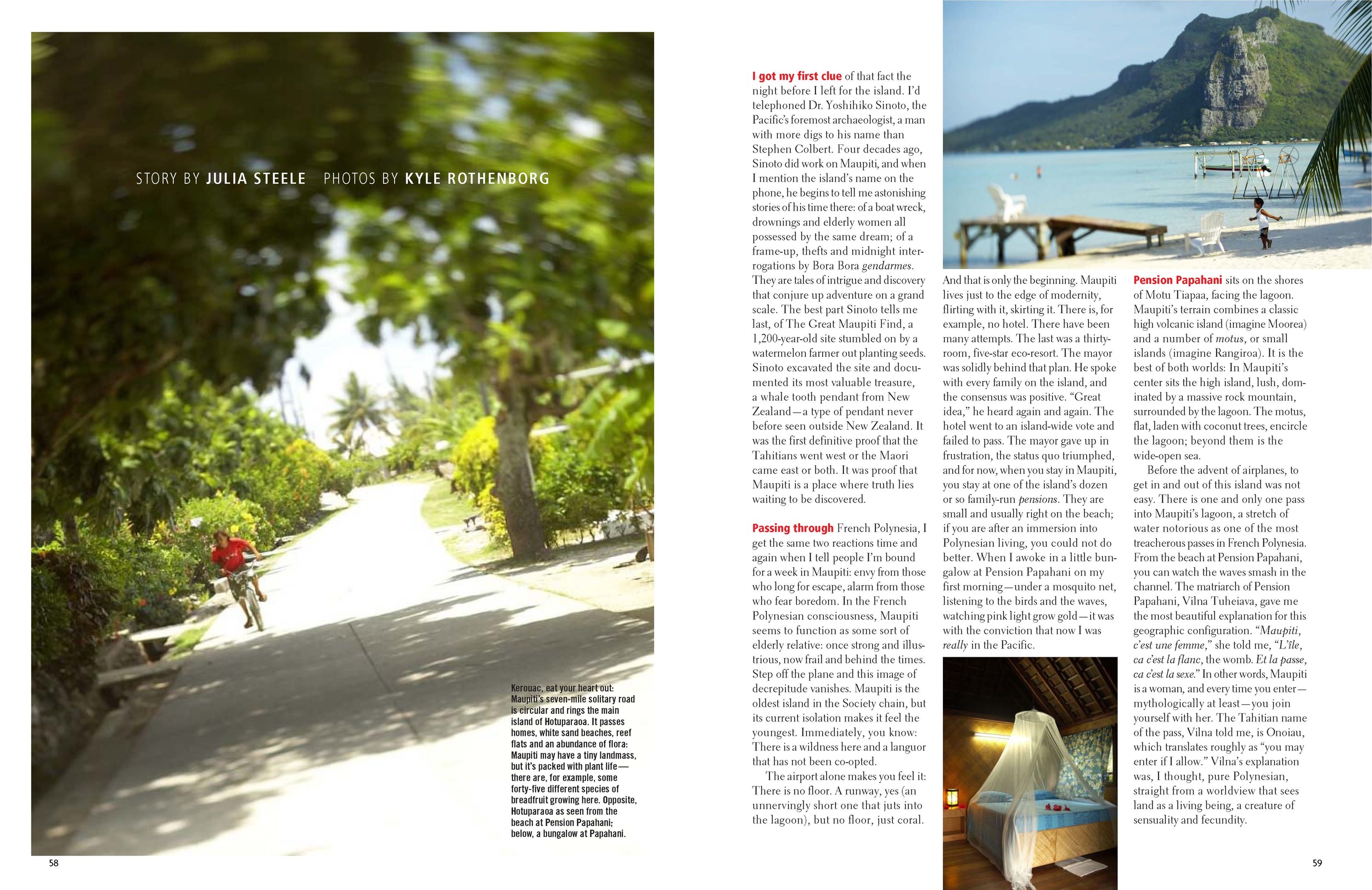

Almost all of Maupiti’s 1,000 residents live in the village, which is on the main island of Hotuparaoa and laid out on a narrow strip of land at the base of the cliffs. Like the airport, it is modern but not: there is a school, a clinic, a food store, a restaurant, a bakery, but these are scattered in among brightly colored houses and easy to miss—there is no center of town, no commercial sector (though several on-the-spot artisans do hang signs in their front yards advertising handicrafts for sale—pearls, shells and the like).

A paved road runs the circumference of Hotuparaoa: Outside the village, the road is hugged by rainforest; in the village, it is hugged by the houses, and their closeness creates an instant intimacy—it is almost as if, as you traverse the road, you are calling on people’s doorsteps. The openness with which life is lived here only contributes to that sense—people call out “Ia ora na!” as you pass, invite you to stop. A gregarious guy named Albert insists that I must rest awhile and help him practice his English; a lovely woman named Carmen invites me to stop and look at her inventive shell jewelry as she tells me the odyssey of her life—of her husband, her children, her move from the Tuamotus to Maupiti over two decades ago. Travel this road and you hear snatches of conversation, music playing, children shrieking.

And there is something else that deepens the intimacy: the graves. Maupiti has no cemetery, so when a person dies, he or she is buried in the family’s front yard. You pass dozens and dozens of gravestones, many decorated with pictures, flowers and candles; it is easy to feel part of both the mourning and the remembrance. As we spoke, Carmen was sitting right next to her husband’s resting place. “Mon mari,” she indicated simply, “c’est ici avec moi. He is here with me.”

Midway through the village is the mairie, the town hall, where I visit the mayor, Paul Ropiteau. Sinoto had asked me to say hello to Ropiteau on his behalf, so I park the bicycle I’ve rented and go looking for him. I find him sitting in his office, with the sea literally lapping against the window. Ropiteau is the only mayor I’ve ever met who wears shorts and rubber slippers as formal attire—but even in that outfit he is utterly distinguished, with gray hair, a chiseled face and the quiet confidence of happiness. The 73-year-old Ropiteau spent decades in Papeete as a top cop, then retired and came home to Maupiti, the island of his birth. When a mayor was needed, he ran and took the job. He is in his second term now—his last, he says—though he enjoys being the mayor. “The people here aren’t negative,” he says. “They don’t create problems.” A dream constituency, though it is hardly an easy job: Ropiteau deals with economic issues, waste disposal questions, water quality and energy concerns, health matters and more—all pressing issues on Maupiti, as they are across the globe. He still rues the defeat of the hotel—he supported it, he says, because it would have allowed young people a way to make money and stay on island—but he shrugs with resignation. That issue, he seems to say, will pass to the next mayor.

We talk of Ropiteau’s father, who lived a life worthy of Shakespeare. Andre Ropiteau was a wine merchant and bon vivant from France out traveling the globe in the 1920s and ’30s; when he reached Maupiti, he was overjoyed by its beauty, its harmony, its rightness, and he made it his home. He’d fall in love, leave to sell wine, return, fall in love again. “La belle vie,” Paul says wistfully, decades later, “la belle vie.” Eventually, Andre married a stunning woman on Maupiti, and they had a baby, Paul. But Andre had to go back to Europe and there he was trapped by World War II. He was drafted, and two days before the end of the war, he was killed. His journals, published in 1959 as Mon Île Maupiti, form the only book about the island that exists—a chronicle of days of ease, an evocation of joy.

Things are so informal on Maupiti that you don’t really expect to find a tour guide—at least, I didn’t. But when I stop to talk with a young man along the road, he suggests that I ask his uncle Gustave Taero to take me around the island; Gustave has just started a one-man tour operation called Tupuna Vision. “Come to our house in the morning,” the young man advises. So early the next day, I catch a ride across the lagoon on the school boat and walk to Gustave’s house. He’s waiting. Gustave has a serious air, and before anything, he wants to explain his company’s philosophy: “There are many things tupuna [elders] give us for today, and today many people forget, and it’s very difficult to find the gift of the tupuna.” And so, he says, he feels he must do all he can to keep the stories of Maupiti’s past alive.

Gustave has no car, and since the supply ship is late, Maupiti is in the midst of an oil crisis anyway. We circumnavigate the island by bike, which at 9 a.m. is easy and by noon is hell. It’s summer, the rains are late, and the heat is all-pervasive, particularly when you are cycling for hours with no shade and no water. The land is stunning—the lagoon tranquil, the clouds fat and billowy above it, the road lined by dozens of varieties of hibiscus or aute. Gustave stops often, to point out, for example, a lava formation that looks like a giant footprint or a rock that resembles a pig—for each feature in the landscape, he has a story. At Vaihau, the great marae, he describes the arrival of chiefs from the Australs, the Cook Islands, Samoa, even Hawai‘i, who came to make sacrifices to ensure their wellbeing.

I’m not sure if it’s heat-induced delirium or the language barrier or Gustave himself, but the stories seem to float away once I ask a question that will pin them down. But after a while I realize that on this particular walkabout, the specifics don’t matter so much—whether this mountain or that was the brother or the little sister, whether it was Maupiti that was making too much noise or Raiatea when the island got banished by the gods—those particulars are for the youth of the island. What Gustave is really teaching me—straight from the tupuna—is that this is a sacred and storied landscape to be venerated.

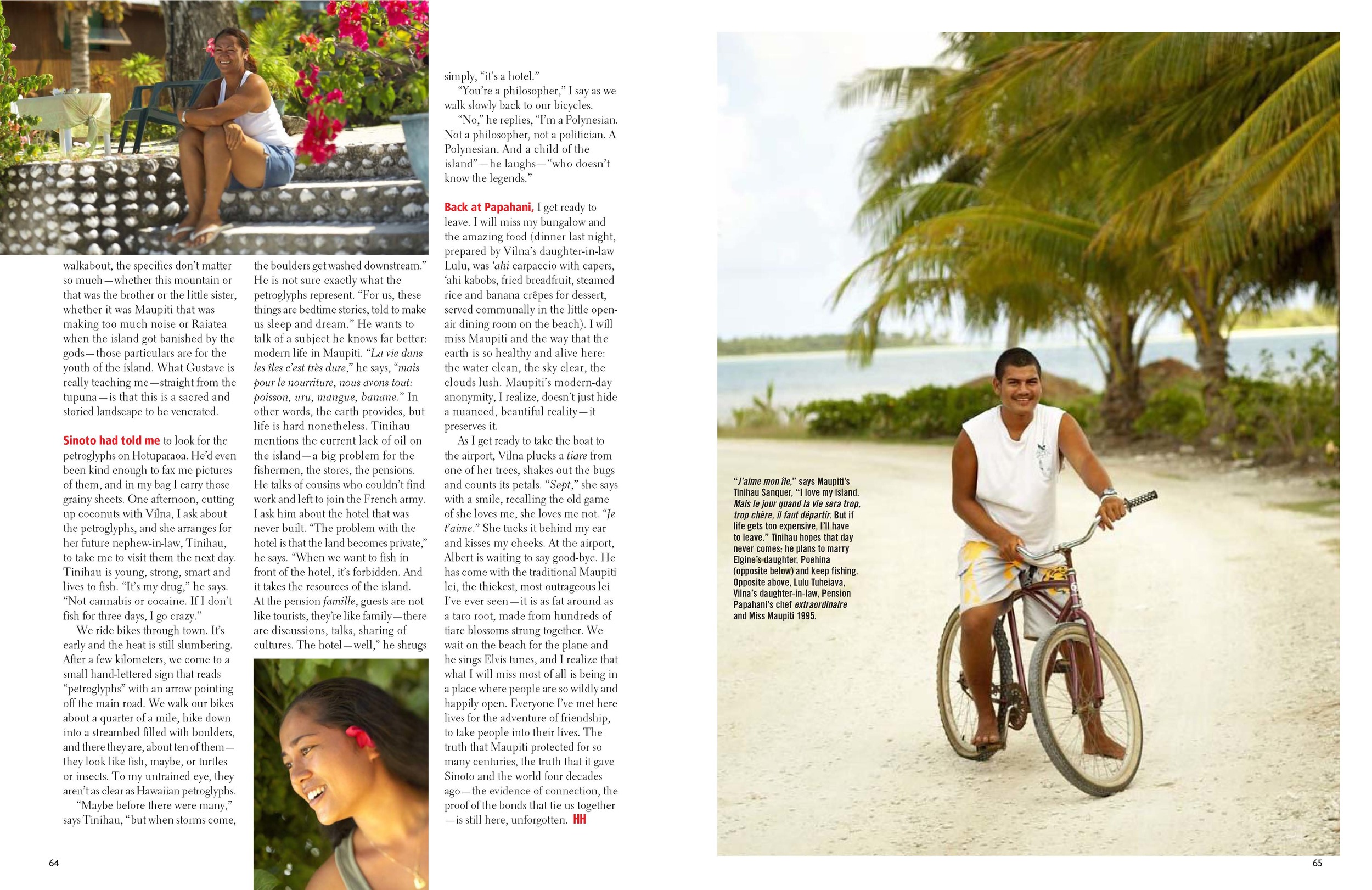

Sinoto had told me to look for the petroglyphs on Hotuparaoa. He’d even been kind enough to fax me pictures of them, and in my bag I carry those grainy sheets. One afternoon, cutting up coconuts with Vilna, I ask about the petroglyphs, and she arranges for her future nephew-in-law, Tinihau, to take me to visit them the next day. Tinihau is young, strong, smart and lives to fish. “It’s my drug,” he says. “Not cannabis or cocaine. If I don’t fish for three days, I go crazy.”

We ride bikes through town. It’s early and the heat is still slumbering. After a few kilometers, we come to a small hand-lettered sign that reads “petroglyphs” with an arrow pointing off the main road. We walk our bikes about a quarter of a mile, hike down into a streambed filled with boulders, and there they are, about ten of them—they look like fish, maybe, or turtles or insects. To my untrained eye, they aren’t as clear as Hawaiian petroglyphs.

“Maybe before there were many,” says Tinihau “but when storms come, the boulders get washed downstream.” He is not sure exactly what the petroglyphs represent. “For us, these things are bedtime stories, told to make us sleep and dream.” He wants to talk of a subject he knows far better: modern life in Maupiti. “La vie dans les îles c’est très dure,” he says, “mais pour le nourriture, nous avons tout: poisson, uru, mangue, banane.” In other words, the earth provides, but life is hard nonetheless. Tinihau mentions the current lack of oil on the island—a big problem for the fishermen, the stores, the pensions. He talks of cousins who couldn’t find work and left to join the French army. I ask him about the hotel that was never built. “The problem with the hotel is that the land becomes private,” he says. “When we want to fish in front of the hotel, it’s forbidden. And it takes the resources of the island. At the pension famille, guests are not like tourists, they’re like family—there are discussions, talks, sharing of cultures. The hotel—well,” he shrugs simply, “it’s a hotel.”

“You’re a philosopher,” I say, as we walk slowly back to our bicycles.

“No,” he replies, “I’m a Polynesian. Not a philosopher, not a politician. A Polynesian. And a child of the island”—he laughs—“who doesn’t know the legends.”

Back at Papahani, I get ready to leave. I will miss my bungalow and the amazing food (dinner last night, prepared by Vilna’s daughter-in-law Lulu, was ‘ahi carpaccio with capers, ‘ahi kabobs, fried breadfruit, steamed rice and banana crepes for dessert, served communally in the little open-air dining room on the beach). I will miss Maupiti and the way that the earth is so healthy and alive here: the water clean, the sky clear, the clouds lush. Maupiti’s modern-day anonymity, I realize, doesn’t just hide a nuanced, beautiful reality—it preserves it.

As I get ready to take the boat to the airport, Vilna plucks a tiare from one of her trees, shakes out the bugs and counts its petals. “Sept,” she says with a smile, recalling the old game of she loves me, she loves me not. “Je t’aime.” She tucks it behind my ear and kisses my cheeks. At the airport, Albert is waiting to say goodbye. He has come with the traditional Maupiti lei, the thickest, most outrageous lei I’ve ever seen—it is as fat around as a taro root, made from hundreds of tiare blossoms strung together. We wait on the beach for the plane and he sings Elvis tunes, and I realize that what I will miss most of all is being in a place where people are so wildly and happily open. Everyone I’ve met here lives for the adventure of friendship, to take people into their lives. The truth that Maupiti protected for so many centuries, the truth that it gave Sinoto and the world four decades ago—the evidence of connection, the proof of the bonds that tie us together—is still here, unforgotten.