David Burney is standing in the middle of a cave on Kaua‘i. Chickens wander in and out, squawking; students mill about, talking. Burney is silent, peering at a small rock he’s holding.

“What kind of rock is that?” someone asks.

“Look how hard it is,” Burney replies. He chips at it. “It feels like granite.”

Except … that that can’t be right because this rock has just been pulled up from a pit ten feet deep on the cave floor. That far down into the earth everything excavated dates from four hundred years ago, well before the arrival of Europeans in Hawai‘i. And this rock, well …

“It’s not a Hawaiian rock,” concludes Burney, who’s now holding a tiny magnifying glass to his eye and peering at the rock again. “The closest place it would naturally occur is California or Japan. Also, it’s an artifact,” he adds, holding it up to admire its rounded form. “It’s been shaped by human hands.”

Out come the theories. Could it be a ballast stone from a “ghost ship,” a vessel that wrecked on the reef offshore after its crew perished at sea? Or could it have come from a ship whose crew was alive and well, a crew that made landfall in Hawai‘i two centuries before Captain Cook? Is there any way a Polynesian could have brought it? “The only place in the Pacific that you can find rock like this is Fiji,” says Burney. Could this bit of rock have been a treasured heirloom transported a millennium ago from Fiji to Tahiti or the Marquesas and then brought to Hawai‘i?

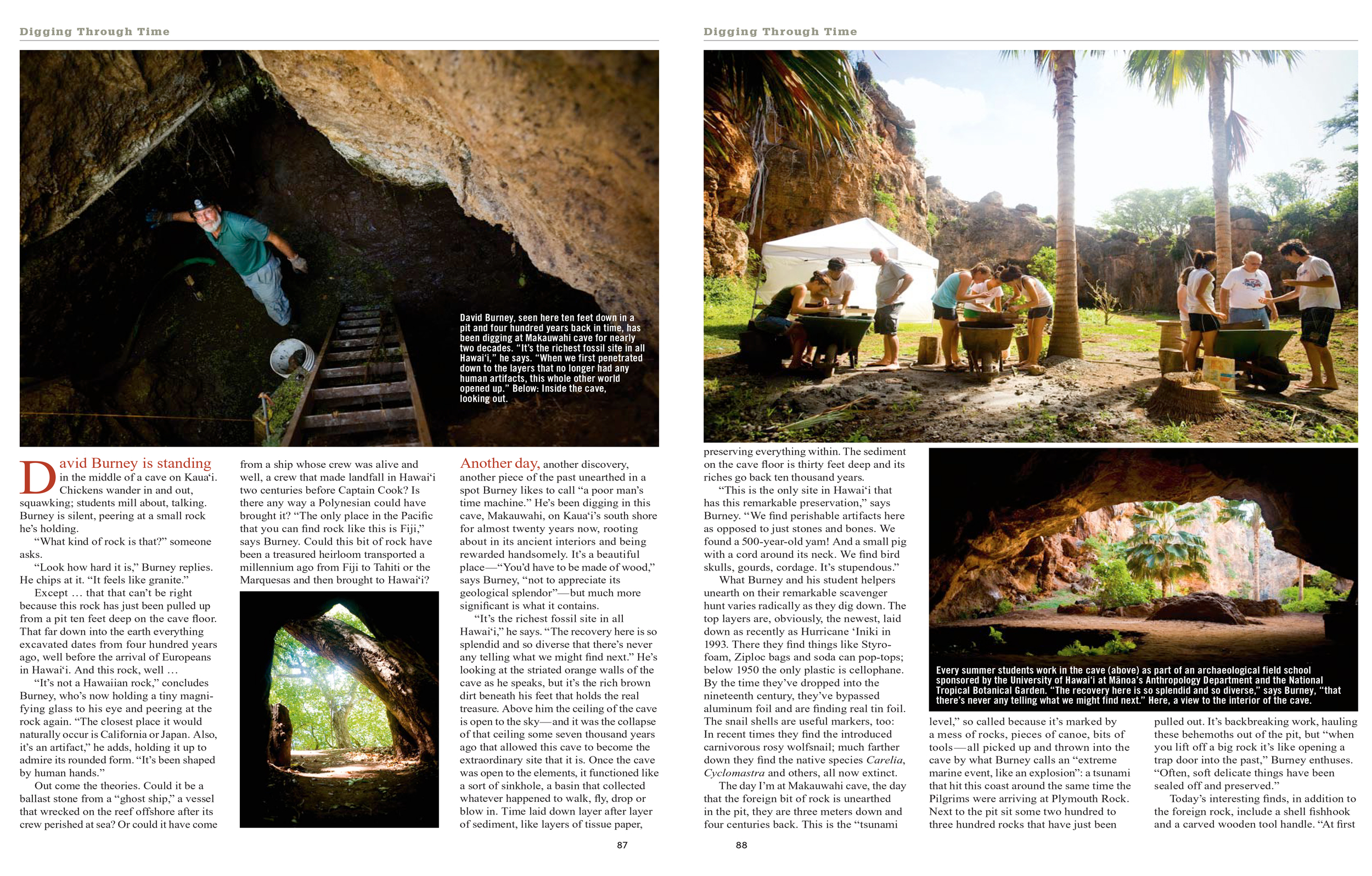

Another day, another discovery, another piece of the past unearthed in a spot Burney likes to call “a poor man’s time machine.” He’s been digging in this cave, Makauwahi, on Kaua‘i’s south shore for almost twenty years now, rooting about in its ancient interiors and being rewarded handsomely. It’s a beautiful place—“You’d have to be made of wood,” says Burney, “not to appreciate its geological splendor”—but much more significant is what it contains.

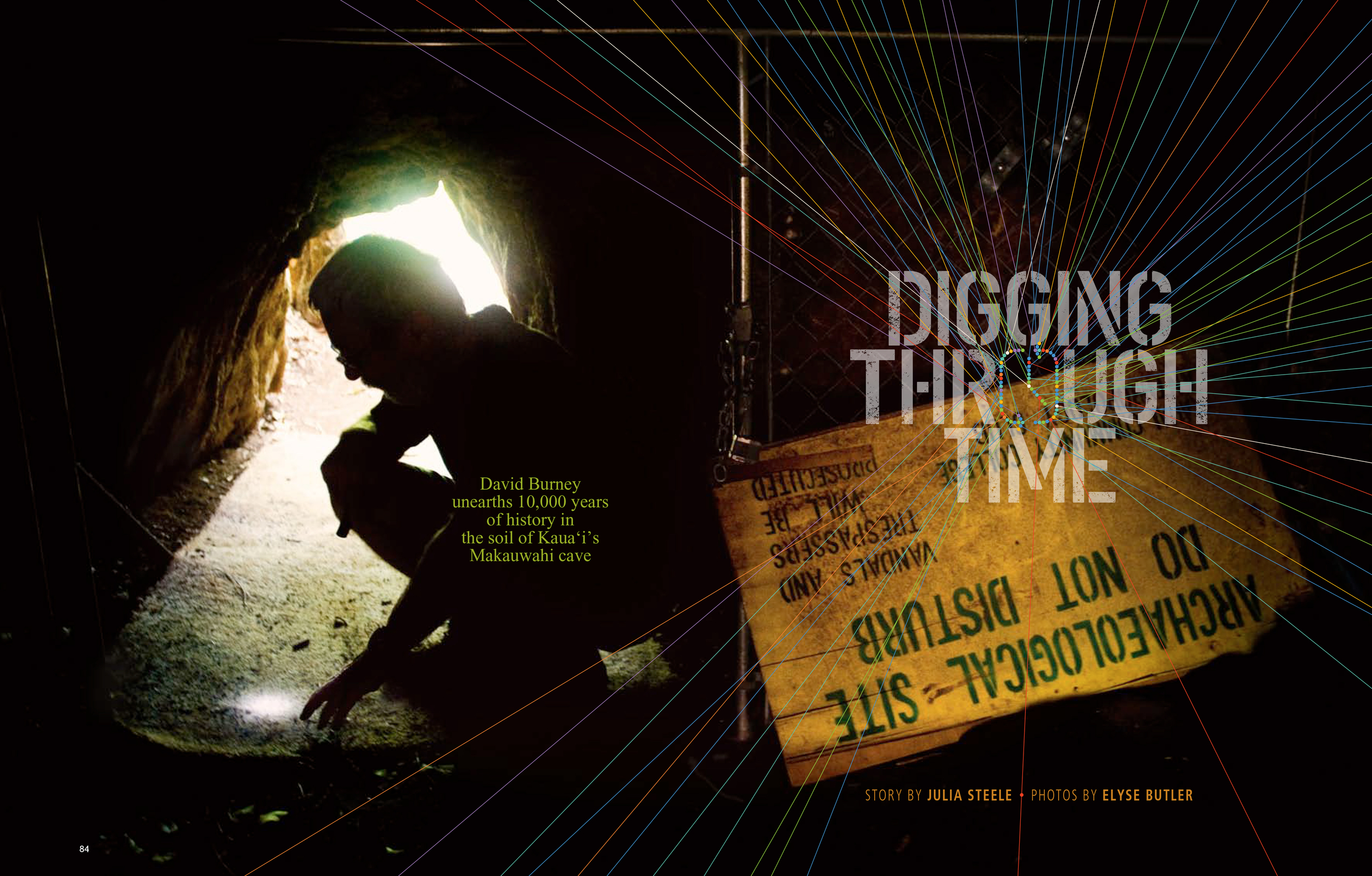

“It’s the richest fossil site in all Hawai‘i,” he says. “The recovery here is so splendid and so diverse that there’s never any telling what we might find next.” He’s looking at the striated orange walls of the cave as he speaks, but it’s the rich brown dirt beneath his feet that holds the real treasure. Above him the ceiling of the cave is open to the sky—and it was the collapse of that ceiling some seven thousand years ago that allowed this cave to become the extraordinary site that it is. Once the cave was open to the elements, it functioned like a sort of sinkhole, a basin that collected whatever happened to walk, fly, drop or blow in. Time laid down layer after layer of sediment, like layers of tissue paper, preserving everything within. The sediment on the cave floor is thirty feet deep and its riches go back ten thousand years or more.

“This is the only site in Hawai‘i that has this remarkable preservation,” says Burney. “We find perishable artifacts here as opposed to just stones and bones. We found a five hundred-year-old yam! And a small pig with a cord around its neck. We find bird skulls, gourds, cordage. It’s stupendous.”

What Burney and his student helpers unearth on their remarkable scavenger hunt varies radically as they dig down. The top layers are, obviously, the newest, laid down as recently as Hurricane ‘Iniki in 1993. There they find things like Styrofoam, Ziploc bags and soda can pop-tops; below 1950 the only plastic is cellophane. By the time they’ve dropped into the nineteenth century, they’ve bypassed aluminum foil and are finding real tin foil. The snail shells are useful markers, too: In recent times they find the introduced carnivorous rosy wolfsnail; much farther down they find the native species Carelia, Cyclomastra and others, all now extinct.

The day I’m at Makauwahi cave, the day that the foreign bit of rock is unearthed in the pit, they are three meters down and four centuries back. This is the “tsunami level,” so called because it’s marked by a mess of rocks, pieces of canoe, bits of tools—all picked up and thrown in to the cave by what Burney calls an “extreme marine event, like an explosion”: a tsunami that hit this coast around the same time the Pilgrims were arriving at Plymouth Rock. Next to the pit sit some two hundred to three hundred rocks that have just been pulled out. It’s backbreaking work hauling these behemoths out of the pit but “when you lift off a big rock it’s like opening a trap door into the past,” Burney enthuses. “Often, soft delicate things have been sealed off and preserved.”

Today’s interesting finds, in addition to the foreign rock, include a shell fishhook and a carved wooden tool handle. “At first this work can seem a little academic,” Burney says, “but then you imagine the guy who last held this”—he proffers the carved wood, and I take it—“a six-foot Hawaiian warrior four hundred years ago.” The handle is smooth, worn, solid. It fits into my hand perfectly. “That’s a guess,” Burney says, as we both imagine the man, the scene, the time. “It’s all a guess. But the more information you have, the more plausible the guess. What we get here is like a very detailed slow movie of the past.”

Burney first dug all the way to the bottom of the cave in 1996, passing through seven thousand years of earthy sediment filled with seeds, insects and bird bones. Then he came upon big chunks of the rock that once made up the ceiling. After that he hit a marine deposit left by rising sea levels that flooded the cave, and for a time he was excavating beautiful seashells. Finally he arrived at the dry cave floor, where he found the pollen of now-extinct palm trees.

The pit he’s digging in today is unlikely to go that deep. In the half-meter below the tsunami layer lies the time of the earliest Hawaiians. Here the soil is filled with rat jaws, chicken bones, kukui nuts, gourds, all the evidence of the plants and animals the Polynesians brought with them. Here, too, are the last remains of many of the native creatures that went extinct after Homo sapiens showed up. “To me the most interesting part of the story is, What did it look like when the first people arrived and what changed?” says Burney. “That’s what’s in this next half-meter.”

Burney has story after story of the things he’s found. There was, for example, the time he came close to $2 million. “Two years ago,” he says in his North Carolina drawl, “I was telling the students that it was hard to date the stuff we were finding, and one of them said, ‘Here’s a silver coin,’ and it had a date on it! It had a little corrosion over the last digit of the date so I saw it was from 1890 something. I turned it over and it was an 1890 something S. I just about fainted. One of the rarest coins in American mintage is the 1894S dime. The last one sold for $2 million. I took it home and put it in a little petri dish of water under a microscope. Somewhere along about midnight the date finally appeared. It was 1895S,” he laughs, ruefully. “I missed it by one year. It was worth fifty bucks.”

The strangest thing, by his reckoning, he ever found? “I pulled up this skull, and I said, ‘I’m not sure if this is even from a bird,’” he recalls. “‘What the heck is this thing?’ It was a strange little skull with a long snout and a real flat head, and its eyes were tiny and way back on the side.” It was a new find for the ornithological world, a little flightless duck with big feet that long ago went extinct.

As for the most important thing Burney has ever found, that encompasses far more than a single object. Really it encompasses every object found in the cave, for the collective picture that they create. “The single most important thing we’ve found,” says Burney, “is absolute proof that prior to humans there was a really remarkable level of diversity here beyond what anybody had imagined. When we first penetrated down to the layers that no longer had any human artifacts, this whole other world opened up. We realized, ‘Here’s the smoking pistol.’ As soon as the humans are gone, there’s evidence of diverse flora and fauna. For example, as soon as you’re past the rat bones, there are all of these seeds from all kinds of trees. We’ve found thousands of bird bones from forty-five species of birds. Then they give out: People arrive and the birds disappear. And there was a mass extinction here of insects.”

Burney has documented three waves of extinction: the first, after the Polynesians arrived; the second, after they’d been in the Islands for some time; the third and most catastrophic, after Cook. “You don’t see any extinctions until humans and then it goes way up,” he says, “and in the last two hundred years, it’s astronomical.”

Burney is no stranger to the impact of humans in the landscape. He got a master’s in conservation biology from the University of Nairobi by living in tents on the Northern Serengeti studying the effect of human activity on cheetahs. He got a PhD in zoology working in Madagascar, searching for the bones of giant extinct lemurs. “If I could characterize what I do,” Burney says, “I find stuff.” He was so good at finding lemur bones that people in Madagascar said it was sorcery.

Burney and his wife Lida Pigott Burny first came to the Makauwahi cave in 1992. Smitten, they traveled to Kaua‘i as often as they could to work and to dig. They moved to the island permanently in 2004 when Burney left a professorship at Fordham University to take over as director of conservation at the National Tropical Botanical Garden—which is headquartered a short drive from the cave.

Today the couple works at the cave whenever they can. Lida spends more time there than Burney now, and it is she who is spearheading the other key project at the site, a project Burney calls “rewilding.” For if this cave is a poor man’s time machine, it is also, he says, a poor man’s Jurassic Park.

“One day,” he recalls, “we were sitting in the cave with all of these seeds and bones piled up around us, and we said, ‘Why don’t we try to bring the landscape back to life?’ Some of the plants we were finding are still with us, even if just barely: on a cliff somewhere or in a ravine.”

They got the seed of the most similar loulu palm they could find, a rare Ni‘ihau palm called Pritchardia aylmer-robinsonii, and planted it. It thrived and today there are more than a hundred of the palms growing in and around the cave, and they are producing seed. Other natives are also thriving: kou, wiliwili, hala, ‘ilie‘e, maiapilo and many more.

When Burney and Lida started their rewilding project, many discouraged them, skeptical that vulnerable native plants would grow in the worn-out cane fields that now surround the cave. “But we’re stubborn, hardworking people,” says Burney, “and we have already had a lot of success.” Today Lida has a six-acre nursery next to the cave where she is raising some one hundred species of native plants to go into the landscape—not just at the cave, but around the island. She and Burney even dream of reintroducing two of the few native birds that have survived into modern times: the Hawaiian hawk and the Laysan duck. “We see their bones everywhere in here,” says Burney. “This is their home.”