The New Boss in Town

In 1985, David Murdock, then (as now) one of the world’s richest and most powerful businessmen, decided to buy the ailing Big Five conglomerate Castle & Cooke. News accounts of the event place Murdock in his Bel Air mansion, lying amid floral-patterned bedsheets, perusing the Wall Street Journal, when he read that C & C was taking on water and sinking fast. A little wheeling and dealing later, the company was his. Soon, everyone in the state was scrambling to figure out what this self-described “expansionist-minded” mystery man had planned for the company... and what sort of businessman he was.

Before long, the 68-year-old Murdock was in Hawaii, at a luncheon at the Halekulani Hotel held to fete him, where he declared, like some sort of boardroom Mark Antony, “I have come to build, not to disassemble.” At the event, Murdock sat with Gov. George Ariyoshi, the editor of Hawaii Business magazine and country and Western singer Kenny Rogers. (Lest you think that last name out of place, think again. In 1986, Murdock brought Rogers—who has announced his intentions to buy property on Lanai—to the Islands to address Lanai residents’ concerns at a meeting of the Maui County Council planning committee meeting. Rogers, who is not a Hawaii resident, has done ads for Dole, and so perhaps felt somehow qualified to assure residents that Murdock would maintain access to Hulopoe Bay and Manele Beach, one of the first concerns to surface when the idea of tourism development was raised.)

The celebrity snow job was apparently not an aberration. In 1985, Murdock, when questioned about plans for Lanai by Hawaii Business, declared, “I have a group of celebrities I would plan on helping to locate on the island of Lanai, thereby helping bring the prestige of the island up. [They’ll be] residents who’ll make investments there.”

Also in that interview, one of the first in which his thoughts on the island were revealed, Murdock stated, “I’m truly interested in the island of Lanai. It’s much more to me than just somewhere to make money. I think I have enough of that. I’m interested in doing something with the island of Lanai that would be beautiful, and that I could be proud of and would be there for hundreds of years after I was gone.”

In fact, this was not the first time Murdock had taken control of an entire area. In a fascinating two-part profile of him published in the May and June 1988 issues of L.A. Business, author William Adler details Murdock’s 1982 leveraged buyout, for roughly $400 million, of the Cannon Mills Co. textile mill in Kannapolis, N.C.: “For 95 years Kannapolis, population 40,000, had been run as the personal fiefdom of the Cannon family... Now Kannapolis was to be David Murdock’s personal fiefdom... (He) laid off 3,000 workers, closed three plants, sold the mill houses, pushed longtime merchants and residents out of downtown for redevelopment purposes, cleaned house of company management, ‘adjusted’ wages downward and put thousands of full-time workers on part-time shifts.”

For a time, Murdock lived in Kannapolis in a $1.5 million Swiss chalet, and, much in the way that he has on Lanai, he contributed to the town’s infrastructure by donating parks and a library, granting a million dollars to the town’s YMCA and building the David H. Murdock Senior Center. He also got into a fight with the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union, which had been attempting to organize Cannon’s 10,500 employees.

“Shortly before the election,” wrote Adler, “Murdock leaked word to the business press that he would consider closing down or selling the plants if the union won... In the end, the company won decisively, getting 63 percent of the 9,500 votes cast.”

Two months after his victory, Murdock announced he was selling Cannon Mills.

To add injury to insult, according a story in The New York Times last year, Murdock reinvested the company’s pension plan holdings in an insurer that was dependent upon junk bonds, making around $30 million for himself in the process. When the insurer, Executive Life, was seized by California regulators, pension payments to Cannon workers were cut by 30 percent. Norman Stein, an expert on pension law at the University of Alabama Law School told angry retirees at a hearing last July, “In real life, dependence on slow-on?the-draw government bureaucrats to regulate grab-as-grab-can David Murdocks has tragic consequences.” The New York Times described Kannapolis as “a dreary indicator of the way that Wall Street’s excesses of the 1980s are playing out on Main Street in the 1990s.”

That’s a taste of Murdock, the businessman. Who is Murdock, the individual? He is ranked 113th in the 1990 Fortune magazine listings of the world’s billionaires, with a net worth of $1.5 billion. He is a staunch Republican, who was a member of Ronald Reagan’s “kitchen cabinet” and co-chaired George Bush’s 1988 campaign in California. He is a collector of Arabian stallions; he has owned up to 200 of them at one time. He is a patron of the arts with a devotion to antiques (clearly evident in Lanai’s hotels) and a passion for the biographies of great men (he claims he never reads novels).

But there does seem to be one key issue with Murdock. Invariably, in profiles negative, positive and neutral, the key issue is always control. By all accounts, he is a hot-tempered man to whom ultimate authority is vital. (“I’m not a normal man,” he told Adler in 1988, “…my thought process is probably foreign to your way of thinking and everything else.”)

A ninth-grade dropout, born in Missouri and raised in Wayne, Ohio, who today describes himself as a man of refined tastes, Murdock was a gunnery instructor during World War II, then bumped around the country, ran a Greek diner in Detroit, got married, wound up in Arizona and made his first fortune developing real estate in Phoenix in the late ’50s and early ’60s. (In 1960, to get out the word on his work in the city, he used the same tactic he employed recently in Hawaii—he purchased a full?page ad in the Arizona Republic that credited his “courage and imagination” for the city’s “spectacular growth.” The ad raved on, “His buildings are testimony to his drive, ambition and farsightedness—as well as his faith in the unbelievably rapid growth and future of Phoenix.”) But, according to Adler, Murdock’s Arizona empire crumbled in the mid-’60s, caught up in a bad real estate market and under investigation by local attorneys and the FBI for fraud. Murdock himself was not indicted in the scandal over bad loans, but five members of one of his subsidiaries were (only one was eventually convicted of a felony).

After losing his money in Arizona, Murdock headed farther west, to California, where he gradually built his empire back up and diversified his holdings. One of his most famous tussles came in the early ’80s, when he attempted a takeover of Armand Hammer’s Occidental Petroleum. Hammer and Murdock became friends when Murdock accompanied Hammer to the Soviet Union to invest $1 million in the Arabian stallion Pesnair. The two subsequently became partners, but went to war when Murdock attempted a takeover of Occidental—he failed, but made a fortune when Hammer bought him out. From there, he turned to textiles in Kannapolis and from there to the food and real-estate holdings of C & C.

Murdock today is chairman and controlling stockowner in Castle & Cooke, founded in the Islands in the last century by two missionaries. Since gaining control of the company, Murdock has, according to Hawaii Investor magazine, cut C & C’s corporate staff in half, dissolved what was left of the company’s corporate operations in Honolulu and sold the 50-acre former site of Dole’s urban Honolulu cannery. He has also, of course, phased out pineapple and introduced tourism to Lanai.

Last year C & C was named one the nation’s “most socially irresponsible companies” by the New York-based Council on Economic Priorities. The council slammed the company for “apparent discrimination- against women, poor community outreach, irresponsible environmental programs, minimal workplace benefits and no disclosure of information.” The council also quoted a union source that accused the company’s foreign operations of making heavy use of pesticides that are banned in the United States.

(In April of last year, The Progressive magazine ran a story on a number of Costa Rican banana farmers working for Standard Fruit—a subsidiary of Dole, itself a subsidiary of Castle & Cooke—who had been forced to work with the toxic pesticide DBCP without any mention of protective gear. At least 2,000 farmers had become sterile, they believed because of their exposure to DBCP, which is known to cause profound organ changes in animals.)

Murdock has also insinuated himself into the East-West Center. In 1989, he was appointed to the Center’s eighteen-member Board of Governors by Secretary of State James Baker, most probably because of his strong standing in the Republican Party, Castle and Cooke’s donations to the Center and his long-term position as a trustee of the New York-based Asia Society. Murdock is described by a Center staffer as a “very active member of the board”; one of his major pursuits at the Center thus far has been heading the search committee for the new president.

“When I think about something I want to do, I do it,” Murdock told The Honolulu Advertiser in 1990. Given his modus operandi to date, it seems safe to assume that Murdock will continue to do things his way, regardless of the consequences. Take, for example, the most widely disseminated anecdote about Murdock on Lanai a couple of years ago: that he once rammed his jeep into a coconut tree to get a coconut. Not true, said a spokesperson to the Wall Street Journal, “He parked his jeep against the palm tree and nudged it.”

The Looting of Lanai

Time and time again, people on Lanai who speak about David Murdock’s plans for the island—both those who are for them and those who are against them—qualify their statements by saying, “Well, he owns it.” Despite the fact that so much of Hawaii’s land was privatized through deceptive means, ownership of land is today the key factor in determining its future. Thus it’s worth tracing Lanai’s ownership from Murdock back to the time when it first passed from the control of the Hawaiians into haole hands.

In 1985, Murdock made a deal with Castle & Cooke—he’d lend them the $258 million they needed to cover their debt to unsecured lenders and in return he’d become chairman and CEO of the company. (He also bought out a rival stockholder for $9 million.) As a result of the deal, Murdock acquired command of the company’s 98 percent of Lanai. C & C itself had obtained Lanai by gaining gradual control of James Dole’s company, Hawaiian Pineapple (later renamed Dole Co.), from the 1930s through the 1960s. In Land and Power in Hawaii, authors Gavan Daws and George Cooper suggest that C & C engineered the gradual takeover of Hawaiian Pineapple when Dole decided to ship his fruit to the Mainland using a rival of the Matson shipping company (C & C was then “an agent and substantial owner” of Matson).

Dole himself had bought Lanai in 1922, for the purposes of expanding his pineapple empire. He paid Frank and Harry Baldwin $1.1 million for the land. The Baldwins, descendants of missionaries who sold to Dole to buy Ulupalakua Ranch on Maui, had raised cattle on the island, as had Lanai’s previous owners, the Lanai Company and Charles Gay. Gay and the company had gained control of their land by purchasing it from a few Hawaiian landowners, the government and the daughter of Walter Murray Gibson—the Mormon renegade responsible for first taking Lanai’s land out of Hawaiian hands.

Gibson’s daughter, Talula Lucy Hayselden, had, with her husband, formed the Maunalei Sugar Co. on Lanai and attempted to grow cane on the island at the turn of the century. The endeavor failed miserably in 1901.

The major endeavor by haoles on the island prior to this time came from missionaries (though a women’s “exile colony,” built to house women who had committed theft or adultery, existed on the northwest point of Lanai in the 1830s and 1840s). Queen Kaahumanu had visited Lanai in 1829 to exhort the people to follow the word of God, and by the 1830s, according to Kenneth Emory’s 1924 survey, The Island of Lanai, the Protestants had erected three schools and a grass house for “Sabbath meetings.”

In 1855, the Mormons arrived, hired land from one of Lanai’s chiefs and began to compete with the Protestants for Hawaiian souls. “The arrival and residence of Walter Murray Gibson at Palawai Basin in September, 1861, marked a turning point in the affairs of the island,” wrote Emory. He then quoted Protestant missionary Dwight Baldwin’s mission report for 1863: “Captain Gibson, as he is called, is said to be the [Mormons’] leader. I cannot learn that he labors much to proselyte the people to Mormonism, he seems to be engaged mostly in agriculture, raising poultry and trafficking with the natives. He has leased lands of the government from the chiefs and I suspect will soon have the resources of the island under his control.”

Gibson had leased Lanai’s Palawai Valley, of which he wrote, in a tone echoed today by Murdock, “There are 10,000 acres of land in this valley, which could probably be bought for twenty five cents an acre or $2,500. I hope to influence the government to let us have all of this valley, and most of the island to develop and then we will dig, and tunnell and build and plant and make a waste place a home for rejoicing thousands ... I would make millions of fruits where one was never thot of. I would fill this lovely crater with corn and wine and oil and babies and love and health and brotherly rejoicing and sisterly kisses and the memory of me for evermore.”

Gibson convinced his Hawaiian followers to work hard to till the land; the money they raised, he assured them, would be used to buy Palawai for the church. The money was used to buy Palawai—but Gibson had the land registered to himself, not to the church. A committee arrived from Utah in 1864 to investigate, Gibson refused to relinquish the land, and he was promptly excommunicated. Many Mormon converts, disillusioned with Gibson, left the island; he stayed on and continued to consolidate his control. By 1869, wrote Emory, “Gibson had control of the better lands on Lanai, and… his Mormon church had dissolved.”

Treasure Island

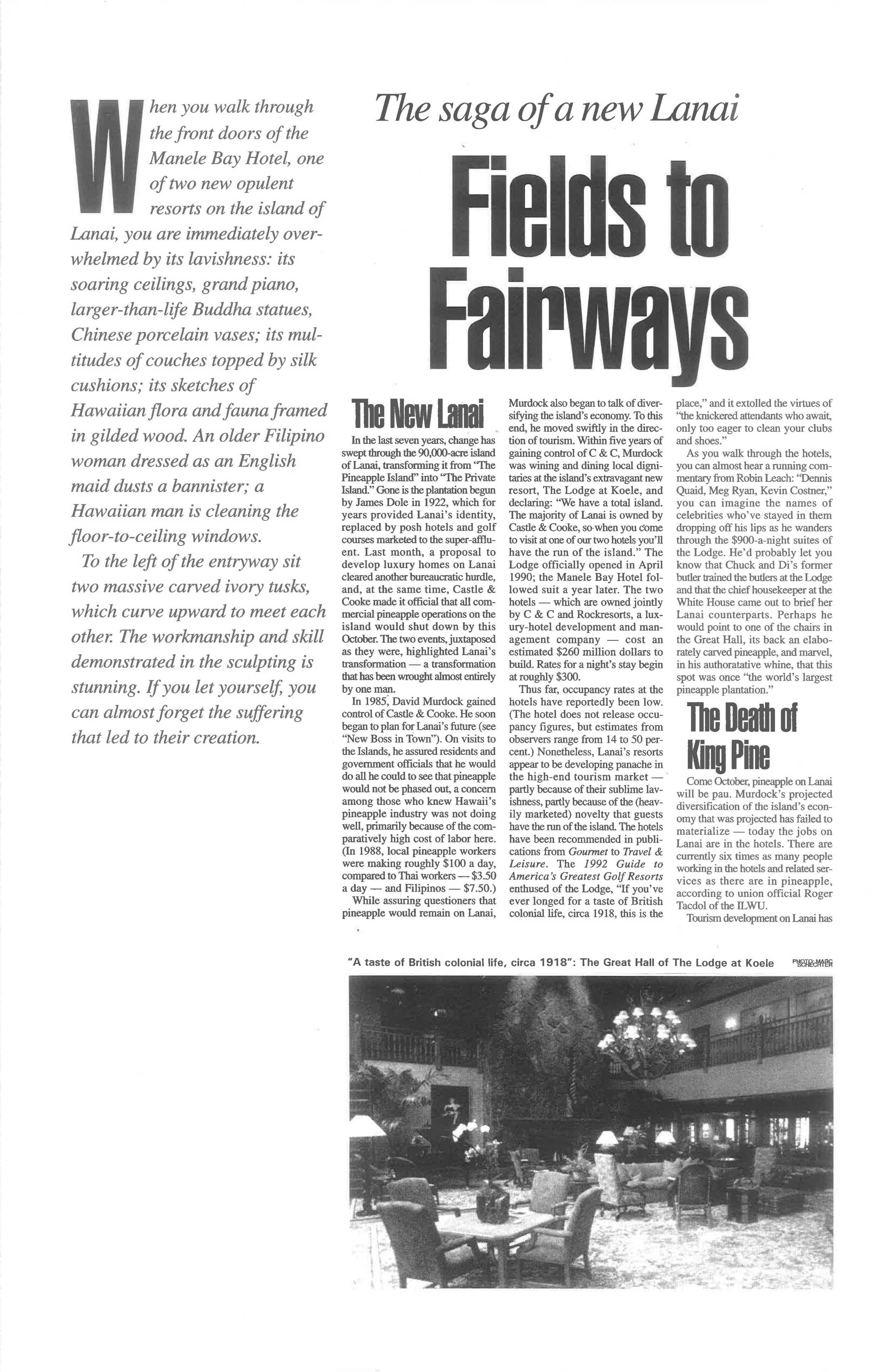

When you walk through the front doors of the Manele Bay Hotel, one of two new opulent resorts on the island of Lanai, you are immediately overwhelmed by its lavishness: its soaring ceilings, grand piano, larger-than-life Buddha statues, Chinese porcelain vases; its multitudes of couches topped by silk cushions; its sketches of Hawaiian flora and fauna framed in gilded wood. An older Filipino woman dressed as an English maid dusts a bannister; a Hawaiian man is cleaning the floor-to-ceiling windows.

To the left of the entryway sit two massive carved ivory tusks, which curve upward to meet each other. The workmanship and skill demonstrated in the sculpting is stunning. If you let yourself, you can almost forget the suffering that led to their creation.

The New Lanai

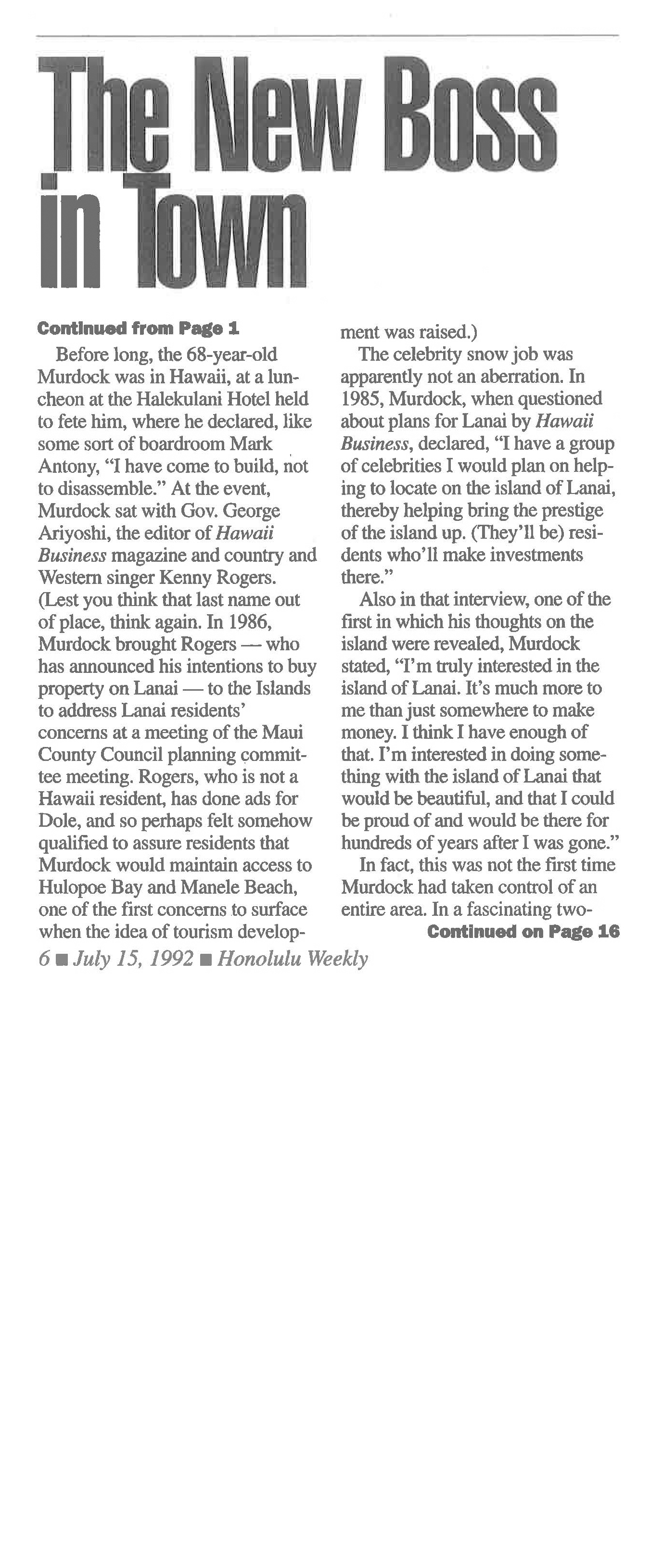

In the last seven years, change has swept through the 90,000-acre island of Lanai, transforming it from “The Pineapple Island” into “The Private Island.” Gone is the plantation begun by James Dole in 1922, which for years provided Lanai’s identity, replaced by posh hotels and golf courses marketed to the super-affluent. Last month a proposal to develop luxury homes on Lanai cleared another bureaucratic hurdle, and at the same time, Castle & Cooke made it official that all commercial pineapple operations on the island would shut down by this October. The two events, juxtaposed as they were, highlighted Lanai’s transformation—a transformation that has been wrought almost entirely by one man.

In 1985 David Murdock gained control of Castle & Cooke. He soon began to plan for Lanai’s future (see “The New Boss in Town”). On visits to the Islands, he assured residents and government officials that he would do all he could to see that pineapple would not be phased out, a concern among those who knew Hawaii’s pineapple industry was not doing well, primarily because of the comparatively high cost of labor here. (In 1988, local pineapple workers were making roughly $100 a day, compared to Thai workers—$3.50 a day—and Filipinos—$7.50.) While assuring questioners that pineapple would remain on Lanai, Murdock also began to talk of diversifying the island’s economy. To this end, he moved swiftly in the direction of tourism. Within five years of gaining control of C & C, Murdock was wining and dining local dignitaries at the island’s extravagant new resort, The Lodge at Koele, and declaring: “We have a total island. The majority of Lanai is owned by Castle & Cooke, so when you come to visit at one of our two hotels you’ll have the run of the island.” The Lodge officially opened in April 1990; the Manele Bay Hotel followed suit a year later. The two hotels—which are owned jointly by C & C and Rockresorts, a luxury-hotel development and management company—cost an estimated $260 million dollars to build. Rates for a night’s stay begin at roughly $300.

Thus far, occupancy rates at the hotels have reportedly been low. (The hotel does not release occupancy figures, but estimates from observers range from 14 to 50 percent.) Nonetheless, Lanai’s resorts appear to be developing panache in the high-end tourism market—partly because of their sublime lavishness, partly because of the (heavily marketed) novelty that guests have the run of the island. The hotels have been recommended in publications from Gourmet to Travel & Leisure. The 1992 Guide to America’s Greatest Golf Resorts enthused of the Lodge, “If you’ve ever longed for a taste of British colonial life, circa 1918, this is the place,” and it extolled the virtues of “the knickered attendants who await, only too eager to clean your clubs and shoes.”

As you walk through the hotels, you can almost hear a running commentary from Robin Leach: “Dennis Quaid, Meg Ryan, Kevin Costner,” you can imagine the names of celebrities who’ve stayed in them dropping off his lips as he wanders through the $900-a-night suites of the Lodge. He’d probably let you know that Chuck and Di’s former butler trained the butlers at the Lodge and that the chief housekeeper at the White House came out to brief her Lanai counterparts. Perhaps he would point to one of the chairs in the Great Hall, its back an elaborately carved pineapple, and marvel, in his authoritative whine, that this spot was once “the world’s largest pineapple plantation.”

Death of King Pine

Come October, pineapple on Lanai will be pau. Murdock’s projected diversification of the island’s economy has failed to materialize—today the jobs on Lanai are in the hotels. There are currently six times as many people working in the hotels and related services as there are in pineapple, according to union official Roger Tacdol of the ILWU.

Tourism development on Lanai has happened swiftly, with very little government intervention. When the company decided to build the Koele and Manele hotels, it was able to get a “negative declaration” for both, which meant no environmental impact statements were required. (Zoning for the projects had been approved in the mid-’70s.) It was also able to complete an eighteen-hole golf course at Koele without doing an EIS.

But eventually C & C began to butt up against concerned residents. After the Maui County Council approved restrictions on the community’s use of Manele Beach (the island’s one good swimming beach and traditionally the recreation area for Lanai), a group of residents formed Lanaians for Sensible Growth, a grassroots organization seeking some accountability from C & C. Members of LSG were angry that the beach would be closed at night (when senior citizens liked to go fishing) and that the hotel would have the right to close the beach during resort functions, a restriction they worried could stretch for days at a time.

“I wasn’t about to let Hulopoe happen,” says LSG member Martha Evans, a teacher at the island’s school. “Too many communities have lost access either legally or because they don’t feel welcome.” After many hours of negotiation, LSG and the company reached an accord that restored full-time beach access.

LSG members stress they aren’t opposed to development per se, they just want to have a say in what transpires on the island: “I'm not against change,” says Evans. “In the entire process, my main goal has been to make this more democratic, to allow people on this island to have a say in their future.” When, citing low occupancy rates, the company argued that the Manele Bay Hotel could not succeed without a golf course, LSG members ended up supporting the course, though they insisted that an EIS must be done first. The company complied. In the end, LSG members were not satisfied with the report’s findings nor its methodology—but the Maui County Council was, and the course went ahead.

The company’s latest proposal is to build a total of 775 luxury homes (350 at Koele and 425 at Manele), which it now claims are needed to make the golf course solvent. The same EIS that looked at the impact of the Manele golf course also looked at the issue of luxury homes; it concluded that they would have no significant impact on the island, a conclusion that flabbergasted University of Hawaii researcher Jon Matsuoka, who has studied Lanai closely. “There’ll be cheap, small housing set aside for blue collar workers pitted against the most expensive housing in the state,” Matsuoka says. “I can’t see how that’s not going to have a social impact.”

Some residents say the logic used to push development through is deceptive and flawed. “First they said they needed the hotel to save pineapple,” says LSG member Ron McOmber, who has lived on Lanai for twenty-one years, “then they said they needed the golf course to save the hotels, then they said they needed the luxury homes to save the golf course. It’s pure, unadulterated baloney.”

“With his logic,” says resident Kathy Oshiro, “if Murdock wants to put in a nuclear power plant, he can say, ‘Hey, there’ll be 90 percent unemployment if I don’t get it.’”

Virtually the only avenue for community input to C & C’s plans occurs at periodic public hearings held by the state Land Use Commission and the Maui County Council. But even there, residents may be unwilling to voice their views.

“This is a one-company town, and the company has power and control,” says state social worker Butch Gima, who spent eighteen years growing up on Lanai, moved to California for eighteen years and two years ago returned to the island. “Employees are in a dilemma. You support the project because if you don’t, you have no job. I really feel for the people. If I worked for the company, I’d have a hard time speaking out, too.”

“Where else are people going to go?” asks the LSG’s Evans. “They see high rents on Oahu and Maui, and they’re not skilled for any other job.”

Future Shock

Despite Murdock’s statement at a recent Maui County Council hearing that Lanai is a “happy island,” any semi-astute observer of the island can see that there are tensions.

“It’s hard to measure the notion of whether people are happy,” says social researcher Matsuoka. “I don't know how you get a handle on the concept of happiness in the context of a declining economy. But in the context of a lack of alternatives, people are going to accept development.”

Two years ago, Matsuoka completed a C & C-sponsored survey of 240 households on Lanai, in an attempt to determine how the island’s people feel about the changes. He found much concern about the social shifts that development will bring to the community.

“You can’t understand the change here until you understand what it was like to live on a plantation,” says Pat Riley, who works at Lanai’s school and has been a member of the LSG since its formation. Until just a few years ago, Dole provided its employees with a store, credit, housing and even recreation under the plantation system. “Dole took care of their every need,” says Evans.

“We’re experiencing the end of the plantation,” continues Riley. “I think the community is in a sense of grief. The company is changing the land, the people, the structure of the economy. There’s a sense that now we’re going to be just like everybody else, and we’ll have to confront the same problems as everybody else.”

Gima says Lanai is witnessing increased drug use, increased family violence and a higher incidence of divorce. “People ask, ‘Is there a cause-and-effect relationship [with the development]?’ I say that’s too simplistic, but there’s a correlation,” says Gima. He’s also concerned that, since many parents now work different shifts and even two jobs, teens are taking on parenting roles, and more children are latch-key kids. The community has also been traumatized by an influx of outsiders coming in to work in the hotels. “More transients and people moving in breaks up the tight sense of the community,” says Evans. “In a school year, we used to be fortunate if we had one new student. This year, we had five or six.”

“This is the first time,” points out researcher Matsuoka, “that people on the island don't know each other.”

Housing is a concern for all, even those who are fortunate enough to own their homes. “Last year our house was valued at $124,00,” says Evans. “This year it’s close to $190,000. In a few years, people aren’t going to be able to pay their property taxes.”

Elaine Kaopuiki, an older fourthgeneration Lanaian who plays music in the hotels, says she is concerned that development has sparked racism against Lanaians. “I hate to even use the word,” she says, “but it is happening here. When I call for dinner reservations, they say, ‘I’m sorry, Auntie, we’re not serving the local people.’ Then I go up and see whiteskinned employees eating. Local people are not allowed in the bar with sneakers and jeans. Then the guests come in with sneakers and jeans.”

Gima, too, mentions racism—against outsiders. “I’ve always felt that Lanai was kind of a racist place,” he says. “You pick up this anti-haole sentiment, and I think there’s a high potential for violence for several reasons. I watch the kids in the schools—they deal with struggles with violence. Also this is a male-dominated, macho type of community.”

Last year, a lifetime Lanai resident armed with a shotgun killed one man, badly wounded another and then committed suicide. Both of the men he shot were recent arrivals who had come to work in the hotels. Points out Kathy Oshiro, whose husband Glenn has been battling C & C on the lease renewal for his gas station: “Lanai has the highest number of guns per capita nationwide. In Lanai, everyone has three or four guns. Not because we’re militant, you understand, but because we’re hunters.”

The Bright Side

Despite their many concerns about the impact of development on the island, LSG members and other residents credit Castle & Cooke with making significant infrastructure improvements in the last few years: sidewalks, new housing, a full-time fire department, a full-time emergency medical team, the old nine-hole Koele golf course free in perpetuity, kamaaina rates on the other courses, support for the preschool and the 4-H club and a deluxe recreation center.

“One thing he did that was very positive,” says Kaopuiki, “he made our island look clean. I can only assume he did it so people will like him and think he’s a square Joe. He heard people say they’d wanted a pool for years and years, and he put one in.” According to LSG attorney Alan Murakami, the company has also agreed to donate 115 acres of land to the county for housing, 15 acres for light industrial development and 10 acres for commercial development. It has also committed 100 acres to the state for an agricultural park.

LSG’s Evans says; “I've heard some charges of racism and favoritism at Manele, but the people at the Lodge are basically very happy—they enjoy what they’re doing. Many of them see the hotels as something very positive for the community. There are many on the island· who believe this is a much brighter future. In some cases there's wonderment—we have these clean jobs, we don't have to work in the fields anymore.’”

But some of the arguments that were used to push tourism have failed to hold true. Despite Murdock’s claims that tourism was going to better everyone’s lives, the workers of Lanai are making less than they used to: The ILWU’s Tacdol says the average pineapple wage was $10.36 an hour, while in the hotels it’s $8.49. Tacdol also says that, though no one has been laid off in the wake of low occupancy rates, employee work hours have been cut back.

In defending its development, the company also used the emotional argument that the hotels would enable Lanai’s youth to come or stay home. But a survey of Lanai high school students indicated that only 8 percent planned to stay on the island and work at the resorts.

Back to the Future

People from Oahu always say, “Going to Lanai is like going back in time.” Today Lanai evokes some perhaps unintended eras. “History is repeating itself,” says Kaopuiki, as she sits under a plumeria tree outside her home in Lanai City, while four kittens and two keikis climb on and off her. “When the white man first came, they caught my race at the most vulnerable time and cheated them left and right. Gibson sent orders we couldn’t cut the kiawe trees, and Hawaiians were charged for raising horses, to fish, for kiawe (see “The Looting of Lanai”). Now things like this are happening on Lanai again. Who is going to gain from this development? What is there for me? Nothing but ‘No Trespassing’ signs. What sort of jobs will there be? Limo drivers, maids, housekeeping ... Limos in this town—it does not fit. All I can see is someone’s pocketbook getting heavier.”

“Lanai represents a much bigger picture of the way capital and American corporations have run amuck,” says UH ethnic studies professor Noel Kent, whose book Islands Under the Influence traces the shift in Hawaii’s economy from agriculture to tourism. “On Lanai, there’s a racial hierarchy and a cultural division of labor. We’re seeing the transformation of a stable, high wage industrial economy to a low wage industry, in which layoffs are frequent. Hotel workers are the lowest paid of any major industry in Hawaii. The whole tragedy is that alternatives are not being looked at—on Lanai or in the country—and workers need jobs.”

Walking down to Shipwreck Beach, I am picked up by a Hawaiian man who is one of the few still working for Dole. He’d been out diving the night before and was looking for his wallet, which he’d left somewhere on the beach. He is open, friendly. What does he think about all of the development? As a Hawaiian particularly, he says, he’s opposed to it: “They ought to just leave one place undeveloped. Pretty soon the only thing the Hawaiians will have left is the street names.” His generosity to an outsider feels foreign to me, a resident of an island that has been overrun by outsiders. “You ought to come back and camp here,” he says. “Just show up. If you need a ride from the airport to the beach, give me a call, and I'll come and pick you up.”

Later that day, at Manele Beach, I am again shown the fabled Lanai friendliness. As I come out of the ocean in the late afternoon, an older man with a cooler offers me a beer and a chance to talk story. I’m conscious that, with my pale skin and reddish hair, I must seem an intruder. But the people of Lanai don't seem to see it that way... at least, not yet. He too urges me to come back and camp. “Wouldn’t I need a permit?” I inquire. “Hell, no,” he says. “If anyone gives you any trouble you just tell them you’re a guest of the people of Lanai.”

What does he think about the development? “I don’t like to see it happen,” he says, “but I can’t stop it. Some people support it, some don’t... Some people believe in the Lord, some people believe in Lord Murdock.”