In the beginning, there was a young Hawaiian artist, a blank canvas and a god: Solomon Enos began painting Kamapua‘a in 2004. Solomon was in the back of Nu‘uanu Valley when he started, on fire to push himself. He wanted to work on a new scale, take on a huge canvas, give birth.

And why not? The god he was painting is the ultimate symbol of birth—the manifestation of regeneration, the most fertile akua, or god, in the Hawaiian pantheon. Kamapua‘a is the one who makes love to the earth after Pele’s destruction, the procreator whose fecundity engenders new growth.

And so Solomon painted. Four days after he started, a family of wild pigs showed up, a mother and her piglets. It was a rare thing: People in the area had never seen pigs there before. And it was auspicious: Kamapua‘a, a legendary shape shifter, frequently takes the form of the pig.

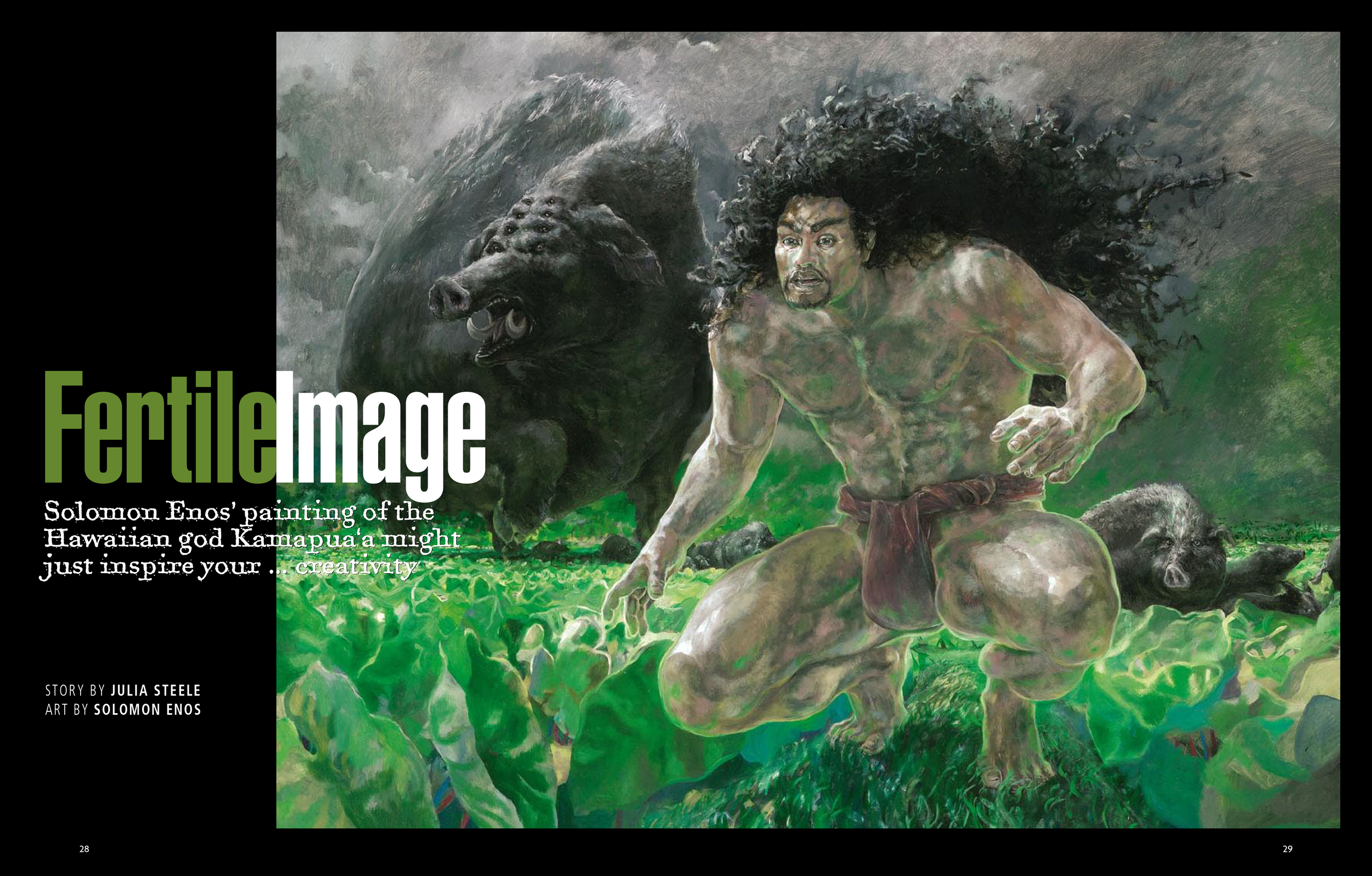

The painting emerged. At its center is the god himself, powerful, vital, on the verge of movement. Is he preparing to go into battle? To chant? To transform himself? It’s impossible to tell but one thing is sure: He is about to act. He is crouched in a sea of taro—another life form he is known to assume—that casts a vivid green light. The light reflects up onto Kamapua‘a’s skin, giving it a green tinge that links god and taro in a glow of life. Behind Kamapua‘a, a family of pigs moves through the field; to the side stands a massive eight-eyed pig, another manifestation of Kamapua‘a, this one as large and immoveable as a mountain and gathering clouds against his kua, or backbone. The sky is filled with clouds. They are heavy and dark, and Kamapua‘a’s hair, wild and full, billows with them in the misty, foggy atmosphere. In contrast to the vibrant green below, everything in the upper part of the painting is black. But this, too, represents regeneration—from the oncoming rain and tracing all the way back to the Kumulipo, the Hawaiian creation chant, in which everything begins in pö, in darkness. “That’s where life comes from,” says Solomon. “You plant a seed into darkness and it seeks light.”

The finished painting is a tribute to the forces that bring life, shot through with potent symbolism. And then something … what is the right adjective? Read on and you can decide … started to happen. Within a month of the painting’s completion, Solomon’s wahine was häpai, or pregnant. And his business partner’s wahine was pregnant. The pair made a number of giclées of the painting—reproductions of Solomon’s imagining of Kamapua‘a, the reproductionist—and began distributing them. And bellies started swelling across the island. Kaipo‘i and Meahilahila Kelling got the painting and a positive pregnancy test. Kealoha and Kalunuola Domingo got the painting, and they too were soon häpai. An admirer of the work purchased a giclée for his kumu (teacher) and before long his kumu’s wife was pregnant. Even the photo editor of the very magazine you hold in your hands—a week after she received an email that contained a jpeg of the painting—found herself with child.

Of course, it could all be coincidence. Babies get conceived all the time, and the Hawaiians are just as famed for their fertility as the Irish. And in these high-tech times of IVF and ICSI and zygotes and blastocysts, talk of the stork has long since given way to the ultra-scientific. And yet, as commonplace and demystified as the creation of life may now be, it remains a miracle, the result of what some call chance, some call fate and still others call divine providence.

So what of the artist—and now father—what does he say? “I just think that there are things that can’t be explained,” he says, circumspect. “I’ve heard it said that if you try to say the Tao, you’re not saying the Tao,” he adds, referring to the enigmatic Chinese philosophy. “If you try to articulate it, you lose it.”

Solomon’s painting of Kamapua‘a stands on its own, but it is also, fittingly, the genesis of a larger endeavor. Solomon is constantly pulling together ideas, events and characters from across centuries and cultures. One minute it will be a Polynesian proverb, the next an idea from Tolkien, the next something he heard on a BBC podcast. But for all his worldliness, he is steeped in his Hawaiianness; he grew up on a farm in the back of Wai‘anae Valley learning the Islands’ legends and history, and his emphasis is there first and foremost. He is a believer that Island deities have wisdom to offer the world and he wants to take these archetypes global.

“In the Hawaiian pantheon, there are really no good or bad guys; everybody’s a little bit naughty, everybody has compassion,” he says. “Kamapua‘a may be a rascal but ultimately he has good aspects. He is a kupua, one who is able to adapt. When he is being chased by Pele, for example, he dives into the sea and becomes a humuhumunukunukuapua‘a. And adaptation is a huge part of what makes Hawai‘i so special. We have plants and animals found nowhere else on earth. Kamapua‘a and that theme of adaptation is a way of understanding evolution.

“Then there’s Pele. She may be violent but after she passes through an area, there’s new growth. So she’s needed. These deities are like forces of nature. … Going back to traditional archetypes as a way to understand who we are and our role on earth is very important. These stories bring together what it means to be human and of the natural world.”

And so the paintings will keep coming. As for the original Kamapua‘a painting, it’s now out in the wider world, discreetly making the rounds in Honolulu to lend its mana, its spiritual power, to the creation of all manner of new things: babies, songs, whatever is sparked.