Ninety million years ago dinosaurs weren’t the only creatures roaming the earth. Hermit crabs were out there exploring, too. These tiny crustaceans have been around far, far longer than us, perfecting the skill of selecting the ideal house and transporting it as needed. Along the way, as members of that much-overlooked group of mini marvels—the marine invertebrates—they’ve played a key role in the evolution of the Earth’s oceans: foraging, scavenging and just generally cleaning up around the place. “The little things that run the world,” is how Susan Middleton describes marine invertebrates, and she has had a particular soft spot for hermit crabs ever since she was a girl and watched them crawling around the beaches and tidepools of her Puget Sound home. Decades later, when she had become one of the world’s foremost wildlife photographers, she was offered the chance to make portraits of hermit crabs and took it. “They are so interesting visually,” she says of her subjects, “their colors and textures so diverse. They are miracles of construction.”

House beautiful: “A house,” the great architect Le Corbusier once said, “is a machine for living in”—and it’s a machine that’s particularly streamlined when it comes to the hermit crab. Hermits need their houses for one simple reason: protection. Unlike shrimp and crabs, whose bodies are entirely covered by a hard exoskeleton, hermit crabs evolved with a soft and vulnerable abdomen that they must safeguard—hence the need for a dwelling. The crab’s twisted abdomen can be curled or flattened to fit neatly into the whorls of a shell, and it has tiny appendages called uropods that allow it to hook on securely. “They have been very successful evolutionarily,” says Middleton. “That’s one of the things that drew me to them. A shrimp relies on speed and agility to survive. A hermit crab relies on armature and its ability to hide.” At left, a Ciliopagurus strigatus or cone shell hermit crab, which has a pancaked body adapted to fit into the narrow opening of a cone shell. This page: Calcinus laevimanus, one of the most common hermit crabs in Hawai‘i’s shallow intertidal areas.

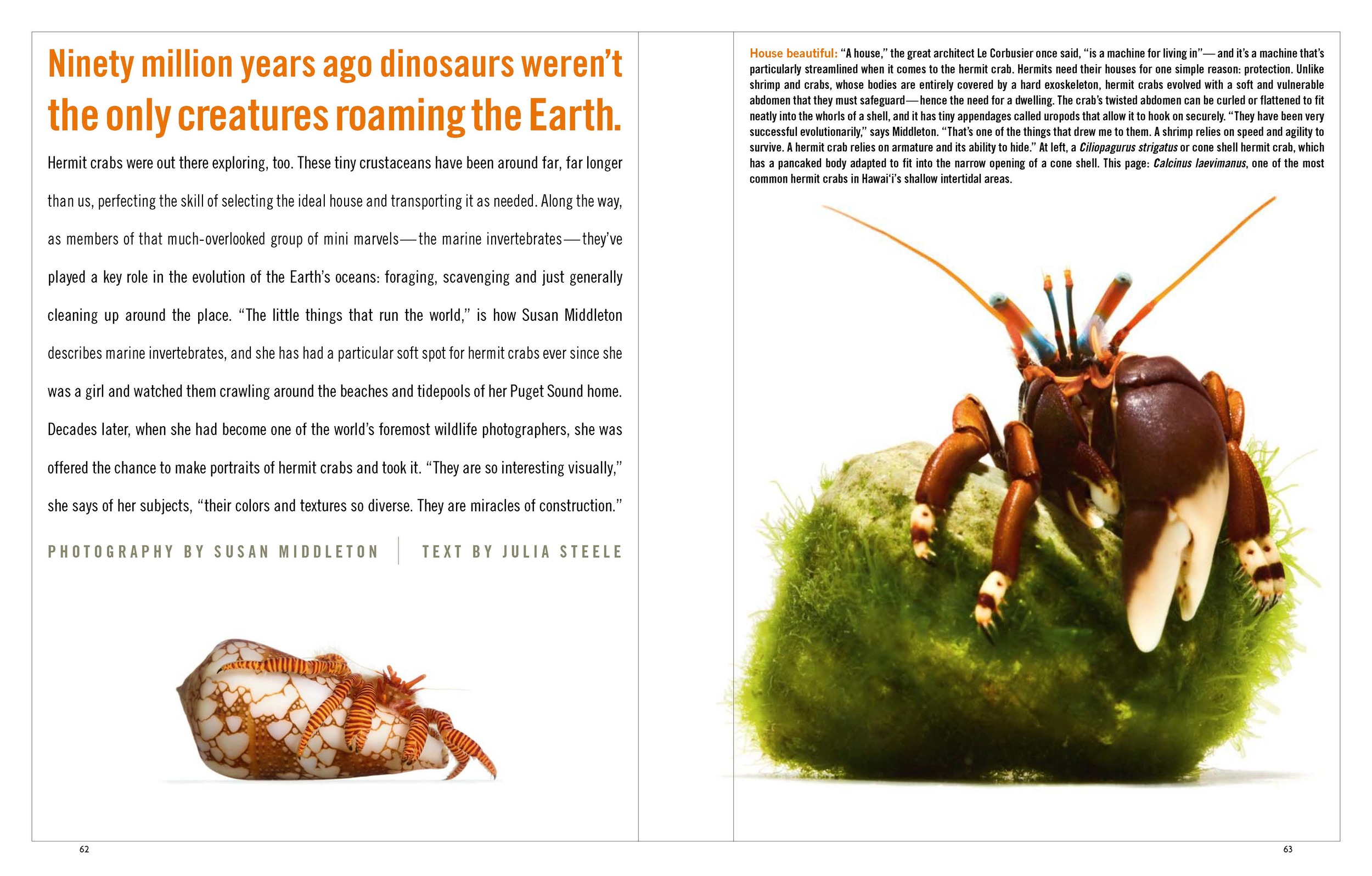

Hat trick: The little anemone topping this Dardanus pedunculatus might look like a dapper chapeau but it plays a far more useful role than simply making its wearer look stylish: The anemone has stinging tentacles, which ward off threatening visitors. The anemone gets something out of the relationship, too: tiny scraps of food the crab casts off as it eats, as well as a free ride across the ocean floor. Given the win-win nature of these partnerships, it’s no surprise that they tend to last: When hermit crabs move from one shell to the next, they detach their anemones and take them along to the new house. When Middleton met this Dardanus pedunculatus in December of 2009, it was on display at the Steinhart Aquarium in San Francisco. Struck by its elegance, she captured it on film. “I have seen crabs spending what seems to me to be an inordinate amount of time tending their anemones,” she says. “It’s like they’re nurturing them, checking them out with their antennae and tending them like a garden.”

Grand Central: This crab, a Dardanus brachyops, has not just one anemone on its shell, not just two but three, as well as a handful of barnacles and the tunnels of a polychaete worm. “So often hermit crabs are living, roving communities of organisms,” says Middleton. “And I really love the gesture this crab is making, too. It’s in motion, lifting itself up on its legs, and it’s strong.” Middleton has photographed about seventy-five different hermit crabs representing some fifty different species. “Their personalities vary widely,” she says. “It takes awhile for their character to be revealed, but the longer you look, the more you see a repertoire of behavior. Some hermit crabs are very aggressive, some very shy.” Middleton has never had a hermit crab for a pet. Still, she says, “Photographing so many, I did grow attached to them. But they all had to go home to the ocean.” Dardanus brachyops, one of the largest hermit crabs found in Hawai‘i, can grow to a length of over eight inches; it lives at depths greater than a hundred feet.

The art of nature: “I photographed this species of crab, Calcinus latens, in a variety of shells,” says Middleton. “I was struck by its green and purple legs, its blue eyes, its gold antennae. It’s gorgeous. And I’m always intrigued by the choices crabs make for their houses. This particular shell looked like an abstract painting to me, really cool and beautiful. I positioned it so that the crab would have to peek out, and for this picture I just had a split second. Photographing hermit crabs does require patience. The task is to put them in a nice aquarium environment with clean, oxygenated water and wait. Initially you may have to wait half an hour for them to come out. Eventually they get hungry or curious, and they emerge. When the flash goes off, they go right back in. But once they’ve come out initially, they come out more quickly. ” Calcinus latens is found throughout the Indo-Pacific and is one of Hawai‘i’s most common hermit crabs; its habitat ranges from shallow intertidal areas to depths of one hundred feet on the reef.

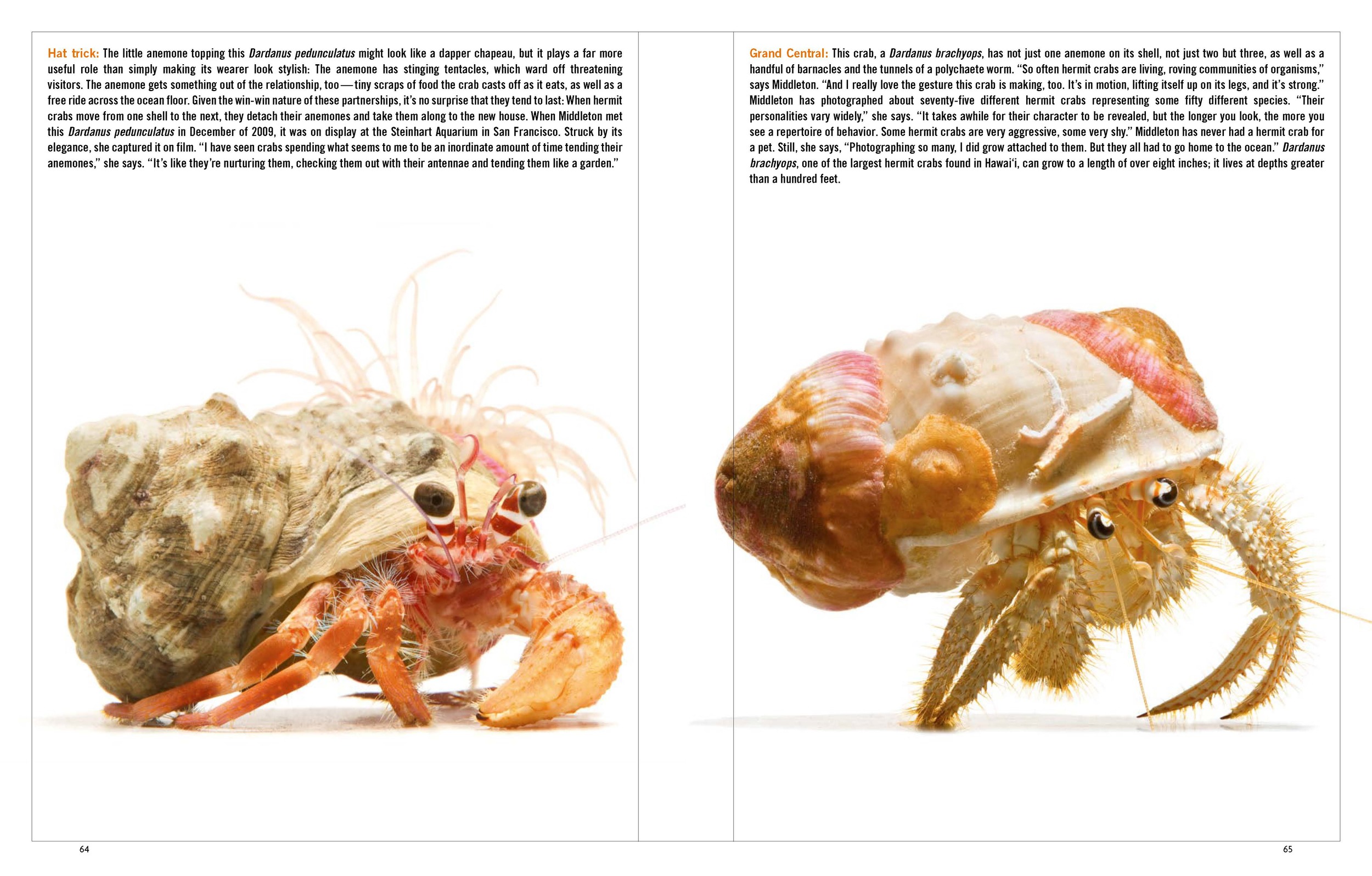

Unidentified crawling object: This crab was collected in October, 2006 from the tropical reefs at French Frigate Shoals, where Middleton traveled as part of a research team focused on marine invertebrates. The team collected from a variety of habitats—tidepools, shallow inshore reefs, deep water—using a number of techniques: baited lobster traps, suction tubes and plain old looking. This crab, collected from a baited trap sunk in waters deeper than a hundred feet, was a stranger to everyone when it emerged from the deep and is likely a new species in the genus Aniculus. At this point there are approximately 1,100 known species of hermit crabs, though others undoubtedly exist in the wild. “Marine invertebrates tend to be understudied and less known,” says Middleton. “There’s speculation that the true number of hermit crab species is somewhere between 1,500 and 2,000, but so little is actually known compared to other animal groups.” Working on-site Middleton has photographed wild hermit crabs in three locales: San Juan Island in the Pacific Northwest, the Line Islands in the equatorial Pacific and the French Frigate Shoals in the Northwest Hawaiian Islands.

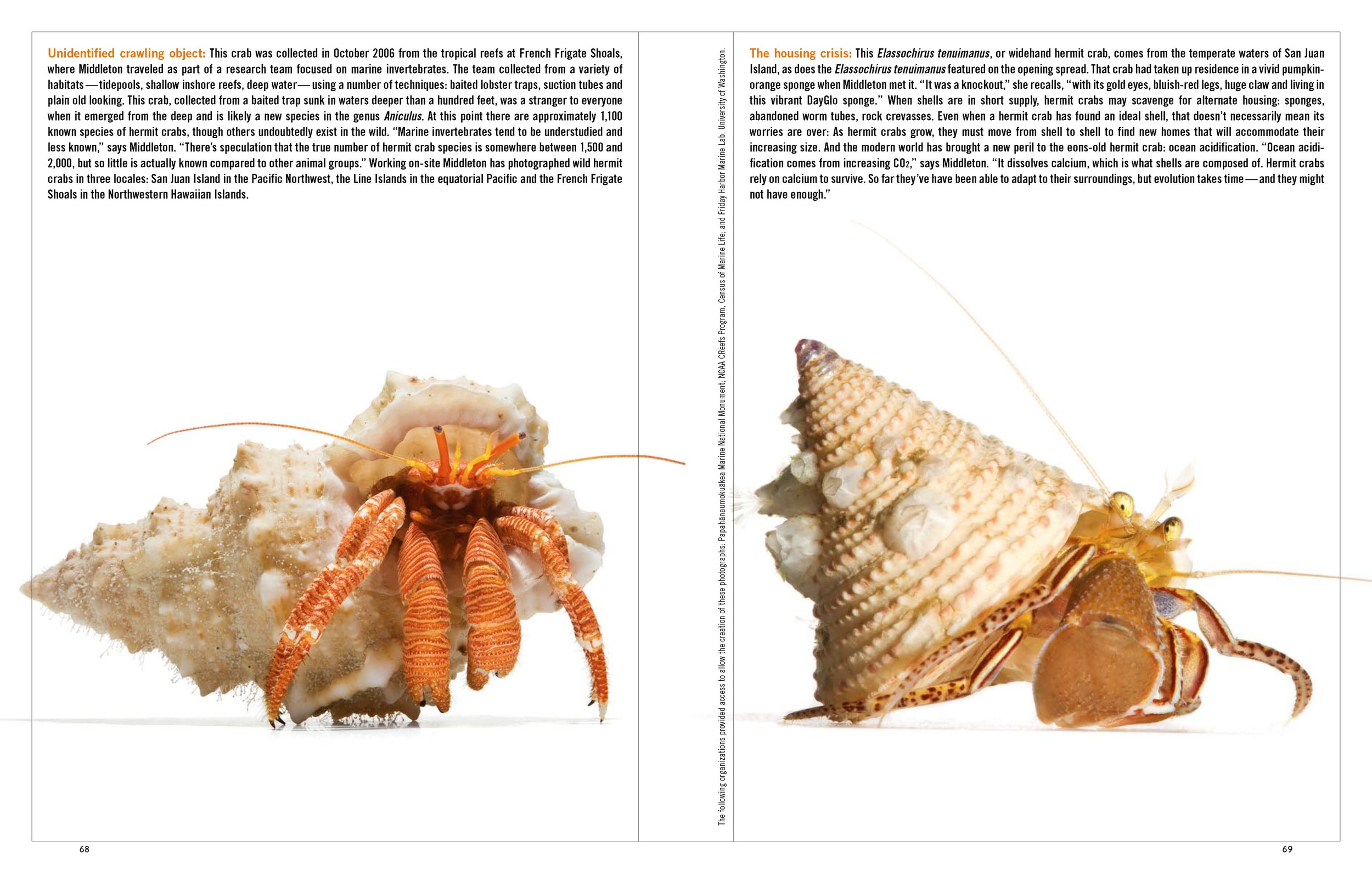

The housing crisis: This Elassochirus tenuimanus, or widehand hermit crab, comes from the temperate waters of San Juan Island as does the Elassochirus tenuimanus featured on the opening spread. That crab had taken up residence in a vivid pumpkin-orange sponge when Middleton met it. “It was a knockout,” she recalls, “with its gold eyes, bluish-red legs, huge claw and living in this vibrant DayGlo sponge.” When shells are in short supply, hermit crabs may scavenge for alternate housing: sponges, abandoned worm tubes, rock crevasses. Even when a hermit crab has found an ideal shell, that doesn’t necessarily mean its worries are over: As hermit crabs grow, they must move from shell to shell to find new homes that will accommodate their increasing size. And the modern world has brought a new peril to the eons-old hermit crab: ocean acidification. “Ocean acidification comes from increasing CO2,” says Middleton. “It dissolves calcium, which is what shells are composed of. Hermit crabs rely on calcium to survive. So far they’ve have been able to adapt to their surroundings, but evolution takes time—and they might not have enough.”