In 1893, Aotearoa/New Zealand made history as the first country in the world to officially and explicitly grant women the right to vote. Other countries followed: Finland in 1906, Russia in 1917, Canada in 1918. The United States recognized the right of every woman in the country to vote in 1920 by ratifying the Nineteenth Amendment to its Constitution—and this year, one hundred years later, women across the United States are celebrating the anniversary of its passage.

But what of women in Hawai‘i? Hawai‘i has always been defined by powerful females, from the goddess Haumea to Native rights activist Haunani-Kay Trask. So how and when did its women get the vote? As good a place as any to start the story is with the vote itself, which was established in the Islands in 1840 during the reign of Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III)—an era when formidable women abounded in the Kingdom of Hawai‘i.

Had you been a diplomat traveling the globe in the early 1840s, you would have found yourself in a world of men. You might have met the occasional queen or empress and the rare female politician, but within the family of recognized nations, by and large everyone would have been male—the presidents, prime ministers, senators, generals, governors, emperors, kings. But in the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi in those years, you would have found a modern government, built around a bill of rights and a constitution, in which känaka maoli (Native Hawaiian) women were the political equals of känaka maoli men. Women controlled vast tracts of land and power all through the government. The reigning monarch, Kauikeaouli, was male, but the kuhina nui—a position akin to prime minister who co-ruled with the king—was a woman: Kekäuluohi (Ka‘ahumanu III). Neither the king nor the kuhina nui could pass laws without the consent of the other. The governors of Kaua‘i and Maui, Emilia Keaweamahi and Kaläkua Kaheiheimälie, were women; on their respective islands, they oversaw taxation, the judiciary and the “implements of war” including munitions and soldiers. Ali‘i (chiefly) women sat in the House of Nobles alongside men and voted as equals with them when they all came together once a year to, under the direction of the constitution of 1840, “seek the welfare of the nation and establish laws for the kingdom.”

That constitution, Hawai‘i’s first, also guaranteed the populace the right to vote for the first time in the kingdom’s history—a foreign concept in the Islands where the power of the ali‘i was seen to come from the gods. The constitution authorized the people of Maui, Kaua‘i, O‘ahu and Hawai‘i Island to elect members of the House of Representatives, who were to serve alongside members of the House of Nobles. The constitution granted the vote specifically to the “maka‘äinana” (in the Hawaiian language) or the “people” (in the English translation). Neither men nor women were excluded from voting for members of the House of Representatives, and given the parity of men and women and the active presence of women in the government, it’s reasonable to think that both men and women were included in this right. In fact, there is disagreement among scholars today about whether the right did in fact extend to women and if it did, whether they actually voted. What is sure is that the women of the aliʻi class who sat in the House of Nobles voted to make law.

Diplomat or not, anyone fortunate enough to be in Hawai‘i in those days would also have seen that the country was changing fast. Hawai‘i in the 1840s—like Hawai‘i in the 1820s and the 1830s—was beset by forces from beyond its borders. There were scourges (foreign diseases, threats of imperialism) and boons (literacy and new knowledge of the world). A constitutional monarchy had supplanted the chiefly system of governance, called ‘ai kapu. Christianity was replacing traditional religion and and extending its values into the laws of the nation. And ideas about women were changing, too. One need only look to the differing mythologies. In the Hawaiian origin stories, divine women were vastly powerful; they created life, waged war, settled scores and often expected, says University of Hawai‘i professor Lilikalä Kame‘eleihiwa, “to be obeyed.” The mythology from the West was different, built from an origin story that saw woman created from the rib of man. Women in this tradition were expected to observe a hierachy that put power in the hands of men and to remain secondary and silent when it came to the affairs of the world.

By the time Hawai‘i’s second constitution was ratified, it was clear which idea was winning—at least when it came to the law. In 1846, a new law had declared that when a woman in the kingdom married (marriage itself being a new institution), her legal rights became the property of her husband. And under the constitution of 1852, even though the Hawaiian version granted the vote to “nä känaka maoli”—“all Hawaiian people”—in the English version the vote went only to “male subjects” of the kingdom: Only men could vote for or be elected to the House of Representatives. If indeed the first constitution had given women a political voice, the second constitution explicitly denied it. Hawai‘i, in those years, was seeking to stave off foreign control and establish its bona fides as a sovereign entity. To get recognition from the West, it followed Western models of governance—and in the mid-nineteenth century, none of those models included women. Women in Hawai‘i were further denied the vote by the constitution of 1864, the constitution of 1887, the constitution of the republic (the government in power after the overthrow of the monarchy in 1893) and again when the United States annexed Hawai‘i as a territory. But these legal denials did not silence powerful women in Hawai‘i, and sixty-eight years after the constitution of 1852, all of Hawaiʻi’s women would get the vote.

According to Kame‘eleihiwa, the first and most vital akua (element) in the Kumulipo, the Hawaiian creation story, is female: Haumea, the earth, who joins with the ocean, the stars and the sun to create all that comes next in the world. O‘ahuʻs first female heiau (temple) was dedicated to Haumea. Pele, Hi‘iaka, Hina ... all female akua are daughters of Haumea. In traditional Hawaiian society, strong women were foundational and female authority was normal. Chiefly women were recognized as leaders, mo‘i wähine, and men who sought to strengthen their own power and that of their offspring did so by joining with women of high rank.

Important ali‘i women were everywhere in Hawai‘i in the nineteenth century. Ka‘ahumanu, the first kuhina nui, was a partner to Kamehameha and broke the ‘ai kapu system. She guided Hawai‘i politically until her death in 1832. Keöpüolani, the most sacred woman in Hawai‘i until her death in 1823, was also a partner to Kamehameha and the mother of Kamehameha II and Kamehameha III. Princess Ruth Ke‘elikölani, the last woman appointed to the House of Nobles, controlled more land in the Islands than anyone but the king; she left it to Bernice Pauahi, who put it in trust for the people. Queen Emma, the wife of Kamehameha IV, waged a campaign for the throne in 1874 and founded Queen’s Hospital and a healthcare system for the nation. Lili‘uokalani ascended to the throne in 1891 as the first queen to rule within Hawai‘i’s monarchy; after she was overthrown in 1893, she remained a moral compass for Hawaiians. And these were just the most famous women leaders of the nineteenth century. There were many others in those years: Kïna‘u, Liliha, Kamämalu, Kekäuluohi, Kekau‘önohi and others. As the Pacific Commercial Advertiser opined in 1919, “The history of no other country shows as many great women as that of Hawaii.”

To understand the history of women and the vote in Hawaiʻi, you have to understand the history of the vote itself. Decisions about who could vote were made against a backdrop of ongoing dispossession. Foreign institutions—Christianity, private land ownership, representative government—all paved the way for non-Hawaiians to take more control in the kingdom. Each successive constitution consolidated the power of these institutions. The 1852 constitution that denied women the vote also gave it, for the first time, to male landowners who were not kingdom citizens. The 1864 constitution added literacy and property requirements to the vote. The 1887 “Bayonet Constitution” denied Asian men the vote; only Hawaiian, American and European men who met even more stringent literacy and property requirements could cast a ballot; citizenship was not a requirement.

In 1890, Representatives William Pünohu White and John Bush submitted a bill to the legislature to amend the 1887 constitution to give women the vote. It did not pass. In 1892, Joseph Näwahï, Hilo’s representative to the legislature and an ardent defender of Hawaiian sovereignty, introduced another bill to give women the vote. It, too, failed. In January of 1893, Queen Lili‘uokalani was preparing to promote a new constitution when she was overthrown. Would women have gotten the vote under her leadership? What is sure is that in the years before the overthrow, efforts were being made to bring more women into the political fold by giving them the vote. Näwahï and Pünohu White were advising Lili‘uokalani on the new constitution. Had the queen succeeded that January, and had the document explicitly given women the vote, Hawai‘i would have been months ahead of its Polynesian neighbor, Aotearoa/New Zealand, which made history by passing its electoral act in September of 1893.

After the overthrow, the men behind it—all of them foreigners or descendants of foreigners—declared Hawai‘i a republic. In 1894, a women’s suffrage committee formed within the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. The group presented a petition for women’s suffrage at the Constitutional Convention of the republic, proposing the vote be tied to literacy and property qualifications that would have restricted it to an estimated nine hundred women. Still the petition failed; the republic’s leaders wanted fewer voters in Hawai‘i, not more. The attitude of opponents was on full display in a piece that ran in the Hawaii Holomua newspaper on April 27, 1894: “Is it possible that there are some ideas in the heads of the gentlemen who are to make a constitution for Hawaii to grant the right of suffrage for women?” it read. “There is politics enough in this country—a great deal too much for the size of it, but if ever the doors are opened to let the ladies—God bless them—into the voting booths the situation would be unbearable.”

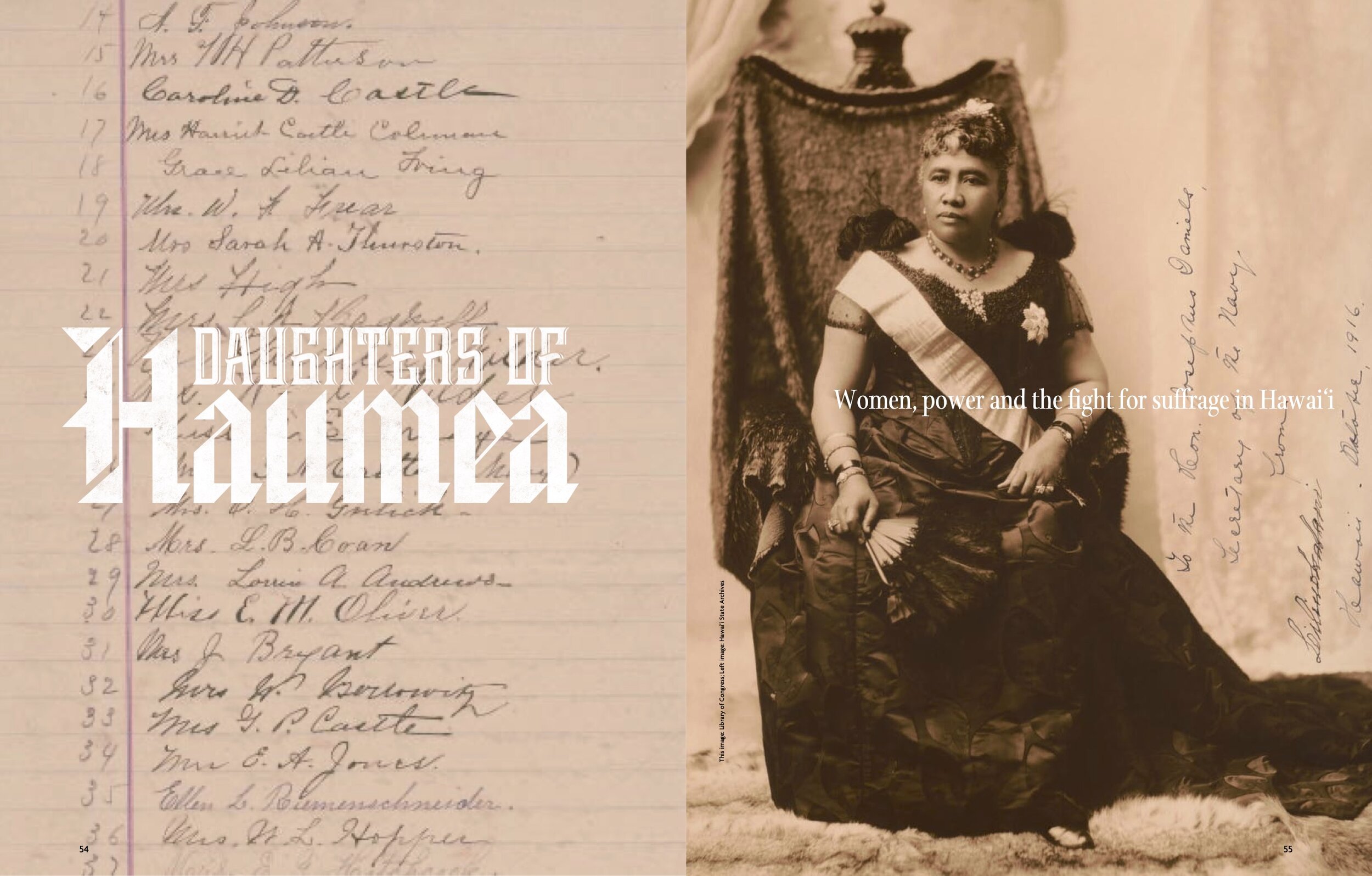

Wilhemine Widemann Dowsett was born in Kaua‘i in 1861, a child of the times. Her mother was an ali‘i Hawaiian, her father a German immigrant and sugar planter. She spoke fluent Hawaiian, German and English, and as a young woman traveled to Europe. When she married Jack Dowsett at St. Andrews Cathedral in 1881, King Kaläkaua, Queen Kapi‘olani, and Princesses Lili‘uokalanai and Ka‘iulani were in attendance. For decades, Wilhemine had witnessed the political machinations in Hawai‘i. They continued when, in 1898, the United States announced its intention to annex the republic and take Hawai‘i as a territory. A petition to the US Congress in 1899 to give Hawaiian women the vote “upon whatever conditions and qualifications the right of suffrage is granted to Hawaiian men” was denied: In 1900, Congress provided the act that defined what Hawai‘i’s territorial government would look like, and the vote went only to men.

But in the ensuing two decades, Wilhemine would join with women across Hawai‘i and with suffragist activists from the United States to advocate for the vote. In 1912, she took on the leadership of the National Women’s Equal Suffrage Association of Hawaii and invited the president of the International Woman Suffrage Association to speak in Honolulu. She wrote to Emma Näwahï, Joseph’s wife, who advised solidarity as a strategy for success. Emma knew well the political power of women—after the overthrow, with Joseph heading the Hui Hawai‘i Aloha ‘Äina, or Hawaiian Patriotic League, Emma helped to create the Hui Hawai‘i Aloha ‘Äina o Na Wähine, an organization of some eleven thousand women dedicated to restoring the nation. When Hui Aloha ‘Äina sent its Kü‘ë Petitions opposing annexation to Washington DC, they were filled with the names of thousands of women.

When she received Wilhemine’s letter, Emma wrote: “If we squabble among ourselves and do not act in unison upon this great question, we will be sorry at the uselessness of our attempt to obtain this privilege.” Hawai‘i’s women did unite. They canvassed, they held meetings, they petitioned the territorial legislature, only to find themselves sidelined time and again by paternalizing and patronizing politicians—though some politicians were with them: The Home Rule Party (the party of Native Hawaiians) had come out in favor of women’s suffrage.

The work played out against a rising tide. More and more women around the world were voting, and across the country, states were granting the right to women even if the nation as a whole had not. Suffragists in Washington, DC testified before the US Congress in 1918 on behalf of women’s voting rights in Hawai‘i; Congress removed any federal obstruction so the issue rested solely with Hawai‘i’s legislature.

In 1919, the Hawai‘i Senate finally passed a bill granting women’s suffrage. Wilhemine worked with women on all of the islands, including Lahilahi Webb on Kaua‘i, Emma Näwahï on Hawai‘i Island and Ethel Baldwin on Maui, to demonstrate popular support for the bill in the hopes that the House, too, would pass it. Advocates sent petitions filled with the names of Island women, and on the day before the vote, the largest crowd of women that had ever assembled in any legislative hall in Hawai‘i—nearly five hundred—filled the House. They earned three minutes of applause as they stood with a mammoth purple-and-white banner that read, “Votes for Women.” But while many legislators professed support for women’s suffrage publicly, they did not want to see it passed until after the upcoming elections out of fear of losing their own seats. The next day, as the House voted, women gathered at a large rally at ‘A‘ala Park, where Wilhelmine denounced the “hypocrisy of the House members who campaigned before the masses about bringing this right to women and now snubbed their pledge to the people.” Snub it they did—the House killed the bill.

The work continued. Wilhemine and others began assembling a massive petition to the US Congress asking it to grant Hawai‘i’s women suffrage directly; Prince Jonah Kalaniana‘ole, Hawai‘i’s delegate to Congress, agreed to introduce it. But in the end it was not needed. In August of 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution was ratified, declaring “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged ... on account of sex.”

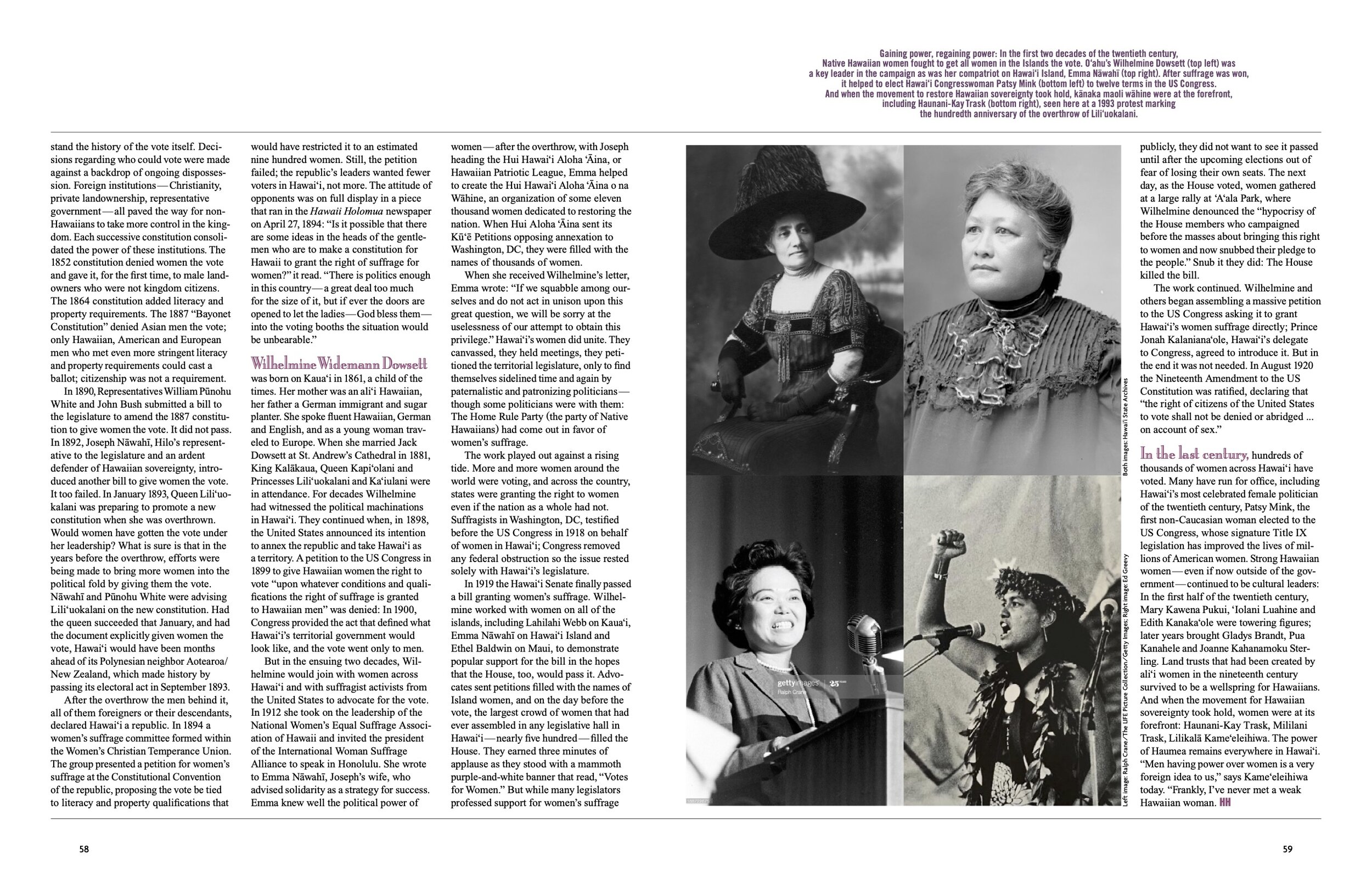

In the last century, hundreds of thousands of women across Hawai‘i have voted. Many have run for office, including Hawai‘i’s most celebrated female politician of the twentieth century, Patsy Mink, the first non-Caucasian woman elected to the US Congress, whose signature Title IX legislation has improved the lives of millions of American women. Strong Hawaiian women—even if now outside of the government—have continued to be cultural leaders: In the first half of the twentieth century, Mary Kawena Pukui, ‘Iolani Luahine and Edith Kanaka‘ole were towering figures; later years brought Gladys Brandt, Pua Kanahele and Joanne Kahanamoku Sterling. Land trusts that had been created by ali‘i women in the nineteenth century survived to be a wellspring for Hawaiians. And when the movement for Hawaiian sovereignty took hold, women were at its forefront: Haunani-Kay Trask, Mililani Trask, Lilikalä Kame‘eleihiwa. The power of Haumea remains everywhere. “Men having power over women is a very foreign idea to us,” says Kameʻeleihiwa today. “Frankly, I’ve never met a weak Hawaiian woman.”