In 1995, Sam ‘Ohu Gon III, along with a dozen or so other ecologists, set out to create a picture of what the Hawaiian Islands looked like before a single human being had set foot upon them. The scientists knew that history had taken the Islands through amazing change in a relatively short time: Two thousand years ago the Islands had some of the highest rates of endemic biodiversity on Earth; they were home to thousands of unique natural wonders and not a trace of Homo sapiens—a radically different landscape from the Hawai‘i of today.

The scientists were ambitious. They wanted to pinpoint the location of every native ecosystem—in essence, to draw a complete map of what the Islands looked like before we all showed up. In the modern landscape, wetlands have been filled in, dryland forests burned and mesic forests cut, but even with all of the change, there are echoes of Hawai‘i’s original richness. Gon, senior scientist and cultural advisor for The Nature Conservancy of Hawai‘i, remembers finding a massive native lonomea tree on the edge of a subdivision in Niu Valley, a living relic that would itself have been hundreds of years old. Out on rough ‘a‘a lava flows, too, there are pockets of plant life that have escaped the ravages of cattle and fire. Old place names offered clues, too, like the fact that Honolulu was once called Kou—in reference to the vast groves of kou trees that once grew there.

The ecologists spent five years researching and refining their map. They honed their ability to discern entire ecosystems from a few tattered remains and trained their eyes to see the signatures of native vegetation. “First you learned to recognize a tree when you were standing right under it,” recalls Gon. “Then you learned to spot it on the ridgeline, then from the air and finally from a satellite photograph.” By the end the scientists had mapped some two hundred ecosystems spread across the island chain—terrestrial, aquatic and subterranean—everything from ‘a‘ali‘i shrubland to koa and ‘öhi‘a montane forest. And it wasn’t enough to simply identify an ecosystem, says Gon: “The challenge was that if you’d described a vegetation type, you had to say where it was and what islands it existed on.”

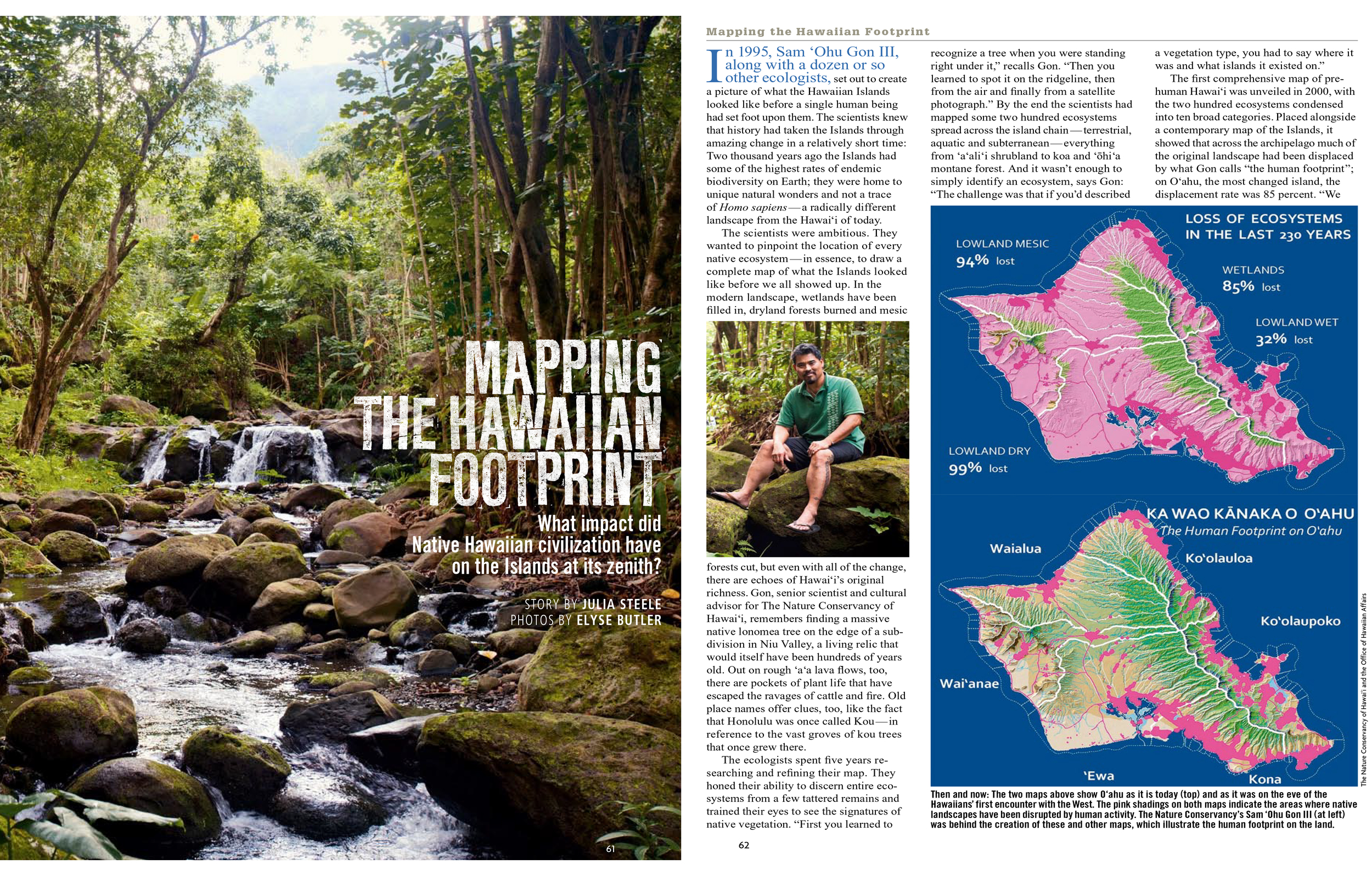

The first comprehensive map of pre-human Hawai‘i was unveiled in 2000, with the two hundred ecosystems condensed into ten broad categories. Placed alongside a contemporary map of the Islands, it showed that across the archipelago much of the original landscape had been displaced by what Gon calls “the human footprint”; on O‘ahu, the most changed island, the displacement rate was 85 percent. “We went from these shadings of greens and browns” representing natives, “to everything in the lowlands turning pink,” representing the human footprint, says Gon. The map quickly became an invaluable research tool—but happy as Gon was with its creation, the project of mapping change was far from over, for him at least. A big part of the picture remained unseen. “For every before-and-after story,” he says, “you have to tell the story of what happened in between.”

The story Gon wanted to tell—the next map he wanted to create—would illustrate that in-between: the ecological footprint of Native Hawaiian civilization. In 2008 he began mapping the pre-contact Hawaiian footprint on O‘ahu. What, he wanted to ascertain, did the island look like in the 1700s, on the eve of its first encounter with the West? Where were its mala ‘ai (fields) and loko i‘a (fishponds)? Its heiau (temples) and hale (houses)? And if modern O‘ahu had lost 85 percent of its original landscape, how much of that had the Hawaiians displaced? Once again Gon faced a daunting task: There were no written records from the time to consult because pre-contact Hawai‘i was a purely oral society. But Gon was nothing if not creative. “We used multiple sources,” he says, adding with a smile, “It was so much fun.” Gon employed three key tools: archaeology, scientific modeling and traditional sources such as chants, mo‘olelo (legends) and the writings of nineteenth-century Hawaiian historians.

Archaeology provided clear evidence of kalo (taro) lo‘i and ‘uala (sweet potato) fields and fishponds. Sites were spread across the island, nestled into valleys and estuaries: crumbling walls that testified to centuries of labor and livelihood. “Hawaiian systems were semi-wild,” notes Gon, “and used natural energies”—stream flow, for example, to irrigate lo‘i and tidal changes to flush fishponds—so human endeavors followed the natural rhythms of the land. “Wet, flat-bottomed valleys are perfect for kalo,” says Gon. “As the population grew, people began to terrace the valleys, go to more marginal places.”

When they arrived on Island shores, the Hawaiians brought some fifty or so “canoe plants” with them from elsewhere in Polynesia. All of these introductions displaced native growth—so as much as we think of the likes of kalo and ‘ulu (breadfruit) as traditional Island plants, they are in fact part of the human footprint. The difference between canoe plants and many more recently introduced plants, Gon points out, is that the canoe plants almost without exception required tending—so the minute an agricultural area was left fallow in pre-contact Hawai‘i, native species recolonized it. Today we have about fifteen thousand introduced plants in the Islands, two thousand of which now grow in the wild and two hundred of which are considered noxious weeds that will choke out native species (trees like strawberry guava, shrubs like miconia). By contrast only one canoe plant naturalized into the wild in any sort of invasive way. You can still see its silvery green silhouette climbing the ridges today: the kukui tree.

Where Gon lacked for actual archeological sites, he used modeling to predict where agricultural sites would have been. He looked at the requirements of two major crops, kalo and ‘uala—the necessary temperature, sunshine, moisture, soil—and went looking for those conditions. The reverse engineering was so effective, it even resulted in the discovery of large ancient ‘uala fields where no previous archeological work had been done.

As the years passed and the research accumulated, Gon filled in the agricultural and marine components of the Hawaiian footprint: the vast fishponds at ‘Ewa, for example, and the lush lo‘i at Waiahole-Waikäne. “From the traditional sources, we identified what were known as the island’s ‘äina momona, or sweet lands,” says Gon. “These were the places that were just amazing resources and celebrated as such—the fishponds of Käne‘ohe and Pu‘uloa, for example, and the fishing grounds of Waimänalo and Waialua.”

The map also looked to the political realities of the island. O‘ahu in the 1700s was divided into six moku, or districts: Wai‘anae, Waialua, Ko‘olauloa, Ko‘olaupoko, Kona and ‘Ewa. As with everything in pre-contact Hawai‘i, the lines tracked the land. “District divisions were ecologically determined,” confirms Gon. Traditional sources—like the mo‘olelo of the exploits of the chiefs—also helped to define the centers of governance and to draw the boundaries of the moku.

The Hawaiian footprint map shows not just the moku, the mala ‘ai and the loko i‘a, but also three other essential components of life on the island: the ala hele (trails), the heiau and other archaelogical sites such as houses and shrines. Information on the ala hele—the early ways that people moved about the island—came from archeological remains and also from the writings of historian John Papa I‘i, who described walking the ala hele as a child in the early 1800s. “Those trails,” Gon notes, “became horse trails and then car trails and then roads and finally major highways.” The map details the heiau of the island, one of the most important of which was Kükaniloko, in the center of the island, where ali‘i (chiefs) were born. Today, Gon says, Kükaniloko is just a place you pass on the way to the North Shore, but centuries ago it was the piko (navel) of O‘ahu.

Gon’s map conjures an island in balance, a place where people were expert at eking an existence out of the natural world. Gon points to population estimates for pre-contact Hawai‘i—“everywhere from two hundred thousand to eight hundred thousand people”—and notes that this, too, was something he re-examined through modeling: Using the estimates of the United Nations’ Food and Agricultural Program, which has done extensive research on the manpower needed to farm lo‘i, Gon and his crew calculated how many people would have been needed to farm the taro lo‘i they’d mapped—keeping in mind that not everyone would have been involved (women, for example, were forbidden from doing this work). Gon estimates that the population was closer to the eight hundred thousand figure—certainly it was large and secure enough, he points out, that “the living was easy and the artwork was fantastic. There were so many amazing artistic expressions—exquisite feather work and the finest kapa (bark cloth) in Polynesia. This was not a civilization on the verge of famine. They had all they needed to create amazing expressions of Hawaiian culture.”

So what of the displacement? Gon estimates that the Native Hawaiian footprint displaced about 14 percent of the original O‘ahu landscape. That figure, though, is not quite as simple and concrete as it looks. Along with the canoe plants, the Hawaiians brought a number of animals with them that had significant effects upon the landscape: rats, pigs and dogs. Rats, for example, ate the seeds of native loulu palms and decimated the trees’ population. Dogs preyed upon native birds. Pigs uprooted native ferns. Even if what was destroyed was subsequently replaced by something native, the transformation had been made. From the moment the first canoe arrived, change was afoot.

When Gon published his completed map, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs immediately took interest: Convinced of the value of mapping out things that were integral to ancient Hawaiian life, OHA decided to sign on to create comparable maps for every island in Hawai‘i. The Nature Conservancy collaborated with OHA on the Maui, Moloka‘i, Läna‘i and Kaho‘olawe maps, and then OHA took the lead from there: It is just completing the Hawai‘i Island and Kaua‘i maps. As each map nears completion, it’s checked by local experts—people like Kepa Maly of the Läna‘i Culture & Heritage Center for Läna‘i and retired state forester Bob Hobdy for Maui—and recalibrated as needed. The maps have also been fine-tuned as new information has become available. “Thank goodness for the Hawaiian-language newspapers,” says Gon, referring to the vast trove of indigenous newspapers published in the nineteenth century. “They are an amazing source, and we can make adjustments as more information comes online. But we think we have a good start.”

For Gon the maps are hardly an expression of the past. Rather, they are “a way to use the lessons of the past to guide our future. We have to value the systems that supported us, especially in an island system with finite resources and space.” To that end, he is already hearing from organizations that want to know what once grew in an area so they can restore it. The former Galbraith lands, for example, which include Kükaniloko, were recently placed into agriculture in perpetuity; people there have looked to Gon for guidance on appropriate crops and growing methods. This, Gon believes, is the real lesson and promise of these maps. How can the modern day be reconnected to the past? Though that, too, is not a simple or concrete question. Even if everything in Hawai‘i aligned to revert to earlier realities, the broader forces at work on the Islands might not be the same as they were a few centuries ago. In the Kula uplands, for example, the moisture band around Haleakalä no longer matches the archaeology of the ‘uala fields—Gon suspects because climate change and deforestation have driven the band farther up the mountain.

And what of Gon? When he travels around the island now, what does he see? A mix, he says, of pre-human, pre-contact and modern-day: He sees across time and generations, across introductions and extinctions, across the past and, he hopes, into the future. “There’s nothing,” he says, “like a map to go with a story.”