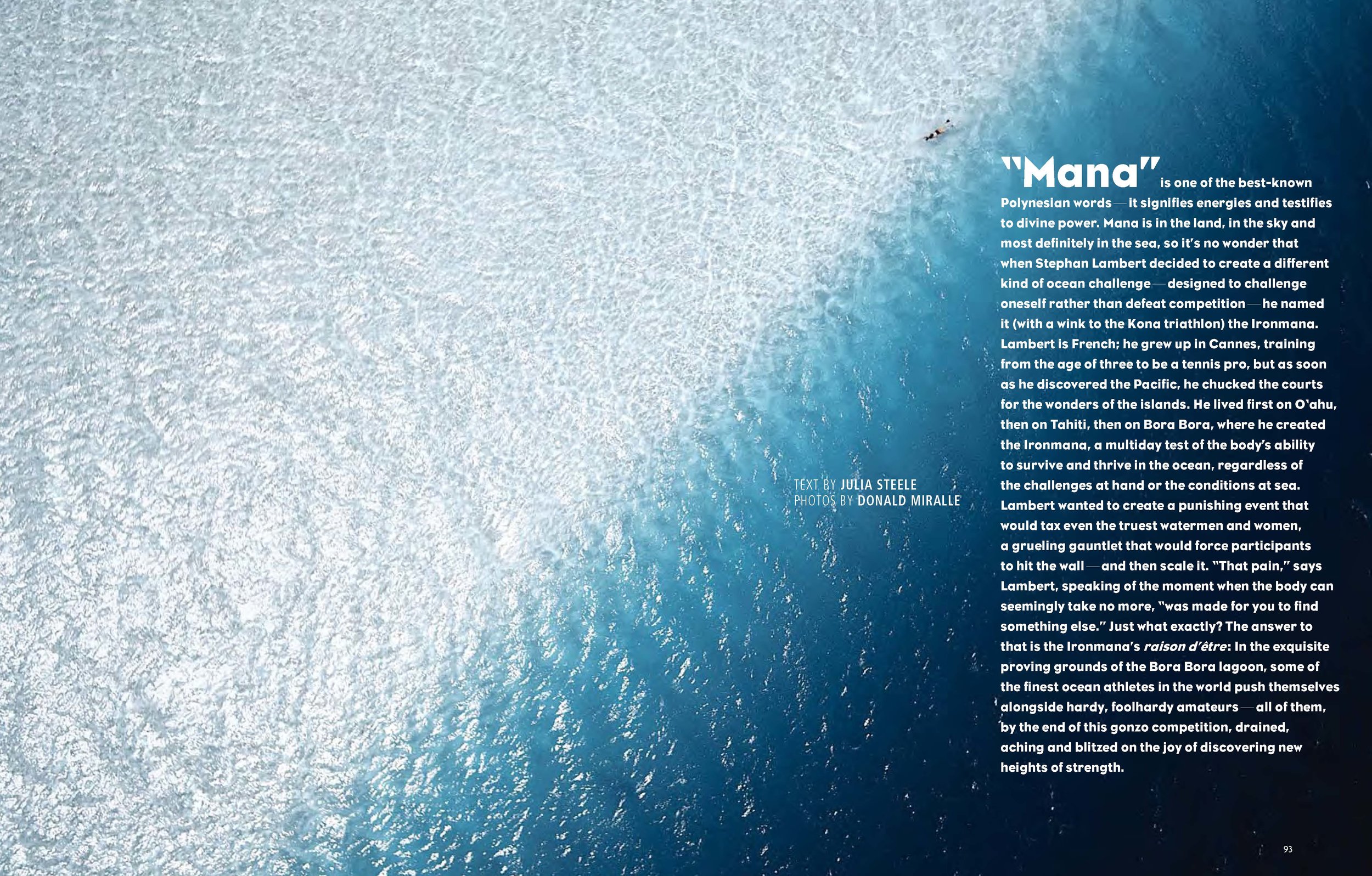

“Mana” is one of the best-known Polynesian words—it signifies energies, testifies to divine power. Mana is in the land, in the sky and most definitely in the sea, so it’s no wonder that when Stephan Lambert decided to create a different kind of ocean challenge—designed to challenge oneself rather than defeat the competition—he named it (with a wink to the Kona institution) the Ironmana. Lambert is French; he grew up in Cannes, training from the age of three to be a tennis pro, but as soon as he discovered the Pacific, he chucked the courts for the wonders of islands. He lived first on O‘ahu, then on Tahiti, then on Bora Bora, where he devised the Ironmana: a multi-day test of the body’s ability to survive and thrive in the ocean, regardless of the tasks at hand or the conditions at sea. Lambert wanted to create a punishing event that would tax even the truest watermen and women, a grueling gauntlet that would force participants to hit the wall—and then scale it. “That pain,” says Lambert, speaking of the moment when the body can seemingly take no more, “was made for you to find something else.” Just what exactly? The answer to that is the Ironmana’s raison d’être: In the exquisite proving grounds of the Bora Bora lagoon, some of the finest ocean athletes in the world push themselves alongside hardy, foolhardy amateurs—all of them by the end of this competition, drained, aching and blitzed on the joy of discovering new heights of strength.

Until the morning of, competitors in the Ironmana never know what any given day’s challenge will be. They gather on the beach soon after sunrise to hear what Lambert has planned, and the only certainties are that it’ll happen in the ocean, and it’ll be hard. On the first day of the 2016 Ironmana, it was a thirty-mile course around the Bora Bora lagoon on a prone paddleboard, much of it, as it turned out, through a monsoon downpour that rendered the ocean a milky turquoise. The next day it was swimming: seven miles in the lagoon. Matt Poole—an Australian with the zero-to-sixty juice of a Ferrari—instantly stroked his way out in front, though the rays in the lagoon showed him what true grace looks like in the ocean. To a one, the athletes who take on the Ironmana say they’re here for the adventure, not the competition. The theme for 2016? Go deeper. “When you are open to the unknown,” says Lambert, “life gives you things.”

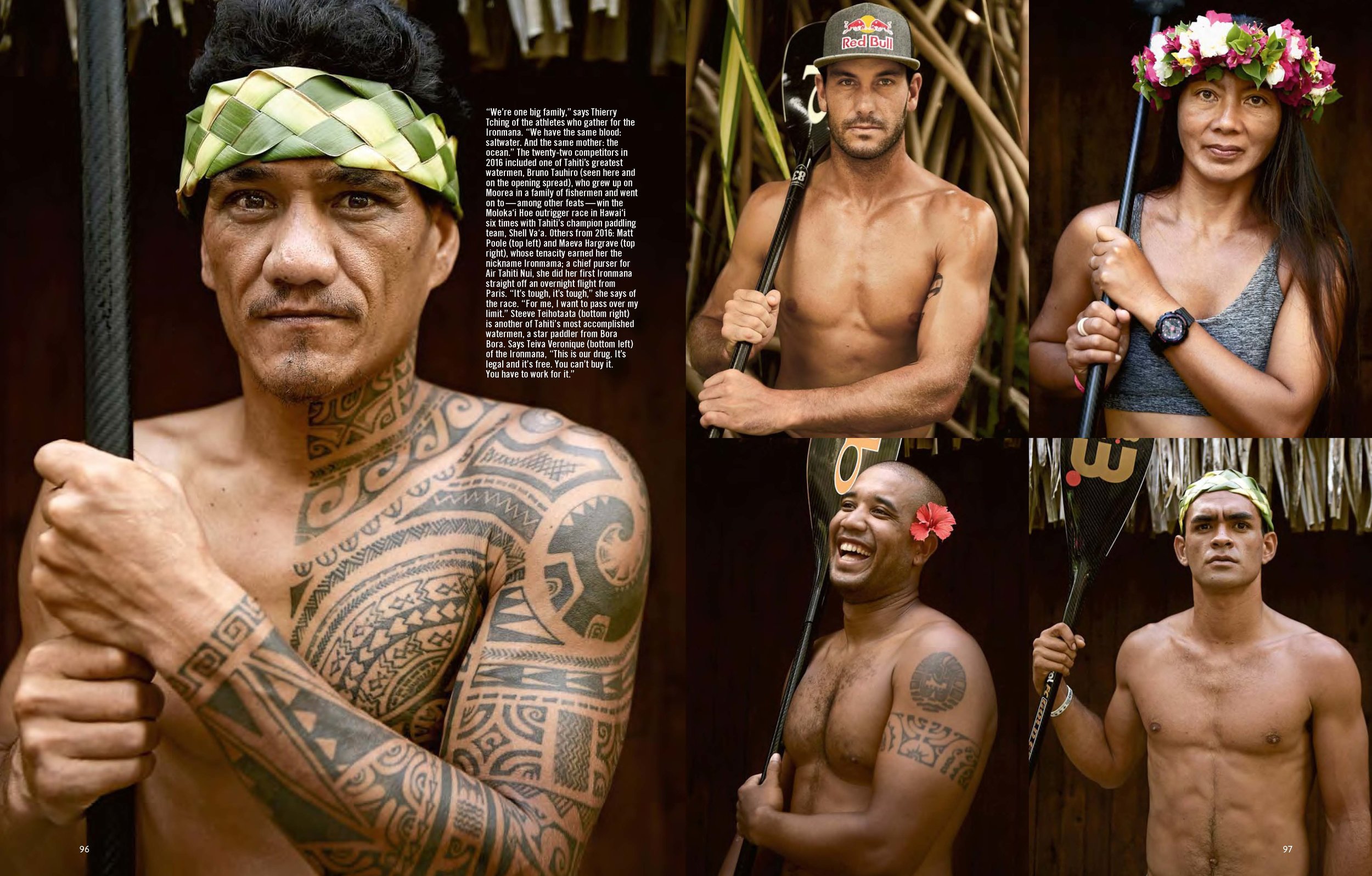

“We’re one big family,” says Thierry Tching of the athletes who gather for the Ironmana. “We have the same blood—saltwater. And the same mother, the ocean.” The twenty-two competitors in 2016 included one of Tahiti’s greatest watermen, Bruno Tauhiro (seen here and on the opening spread), who grew up on Moorea in a family of fishermen and went on to—among other feats—win the Moloka‘i Hoe outrigger race in Hawai‘i six times with Tahiti’s champion paddling team, Shell Va‘a. Others from 2016: Matt Poole (top left) and Maeva Hargrave (top right), whose tenacity earned her the nickname Ironmama; a chief purser for Air Tahiti Nui, she did her first Ironmana straight off an overnight flight from Paris. “It’s tough, it’s tough,” she says of the race. “For me, I want to pass over my limit.” Steev Teihotaata (bottom right) is another of Tahiti’s most accomplished watermen, a star paddler from Bora Bora. Says Teiva Veronique (bottom left) of the Ironmana: ““This is our drug. It’s legal and it’s free. You can’t buy it. You have to work for it.”

Day four—the last of the 2016 Ironmana—was dedicated to stand up paddling: forty miles, all in the lagoon. Here father-and-son competitors Heremoana and Jerome Chapelier arrive to celebration at the finish line. Heremoana, the Ironmana’s youngest contender, had just celebrated his twelfth birthday a week before. He grinned widely at the end but confessed, “My arms hurt.” Seattle’s Jeremy Lewis, a former managing partner at Goldman Sachs and one of three Americans competing in the 2016 Ironmana, called it “the hardest race you’ve never heard of.” Still, beyond the pain, everyone agreed that the mana of the Bora Bora lagoon sustained them—and the camaraderie made everything sweeter. “You fight with yourself, with friends who are doing the same thing,” says Tching. “The movie you make in this race will stay forever in your head.” “Stephan is the guru,” adds Veronique. “He knows better than us what we’re capable of. He imagines the impossible and then shows us it’s possible.”