In a small room in the Auckland War Memorial Museum there is a simple film—no sound, no edits, just an image of black dots and red lines—that sums up the Kiwi character in five minutes. The tiny film is projected onto a tabletop diorama of Mount Everest. A dot appears with the words “base camp.” From it a line runs up until a second dot appears: “camp 2.” The line continues, then another dot: “camp 3.” And so it goes, climbing up. But the line is not direct. It jumps up, falls back. It goes past camp 5, then drops back to 3, then up to 5, then almost to 6, then back, then to 7. It climbs and falls four times before reaching camp 8, tantalizingly close to the top of the world. Then it zips to 9, and from there, finally, to the summit.

That line tells a story of grit, resolve and the lunatic confidence of the pioneer. It tracks the 1953 route of New Zealand’s Sir Edmund Hillary, the first, along with Nepal’s Tenzing Norgay, to stand atop Everest. We all know they made it to the top, but those dots and that line tell the story anew, dispense with myth and drive home the tenacity it took to get up that mountain. Just next to the diorama is the axe Hillary used to cut hundreds of steps in the ice as he ascended.

Hillary’s on New Zealand’s five-dollar bill now, along with a penguin, and he’s as beloved a hero as they come in the country. But he was hardly the sole Kiwi to embody an epic can-doism. In the last year alone, two young women from the North Island showed the world just what New Zealand spunk looks like these days. First there was 28-year-old Eleanor Catton, who in October came from behind to win the Man Booker prize for The Luminaries, a gorgeous, intricate behemoth of a novel—the longest book, by the youngest writer, in the history of the prize. Hot on her heels was Lorde, an out-of-nowhere 17-year-old schoolgirl who bested Katy Perry and Bruno Mars to win this year’s Grammy for best song, Royals. Its refrain, “That kind of luxe just ain’t for us/We crave a different kind of buzz,” says a lot about the national character here at the bottom of the world.

The city Lorde and Catton both call home is winning its own accolades these days: Auckland was just named the third most livable city in the world, behind Vienna and Zurich. Throughout the twentieth century Auckland was a classic backwater: a sleepy God-save-the-Queen colonial town in a place most famous for sheep and rugby. Anybody who flew south to the Antipodes and wanted cosmopolitan headed to Sydney. But that’s all different now. The week before I arrived in Auckland, Springsteen was playing; the week I left The Stones were scheduled. Down at the harbor a Russian billionaire’s superyacht sat out in the bay, and the planet’s über athletes gathered for an international triathlon. At the razzmatazz needle on the city’s skyline, casino junkies were getting their fix. Even Will and Kate and baby George showed up in Auckland while I was there, to race America’s Cup boats, drink sauvignon blanc and give the papers a chance to work themselves into a frenzy (Sample headline: “Kate’s sips of wine quench pregnancy buzz.”)

These days Auckland is home to some 180 nationalities, recent immigrants from around the world. The newcomers join the tough, daring immigrants who sailed from Tahitian beaches ten centuries ago and the tough, daring immigrants who sailed from English seaports two centuries ago: the Maori and the British, who together have forged the modern nation of Aotearoa/New Zealand. That nation is now much respected—this year it was named the most socially progressive country in the world by the Social Progress Imperative—and Auckland, with 1.5 million people, is its epicenter.

But for all its newfound glitz, the Kiwi mothership remains a very intimate little city. When I got on the bus and asked for directions, the Tongan driver delivered them with the gravitas of an elder statesman before flashing a beatific smile. When I walked through the wide-open fields of the city’s central park I came upon several hundred Samoan girls in the midst of a cricket competition. In a sweet little collective of restaurants called Elliott Stables, I met a chef from Kerala named Georgie who made the best dosa I’ve had outside of India; in the dessert shop next door was Natasha, a young Russian who crafted lemon meringue pies by day and novels by night.

Out exploring on my second evening in the city, I came upon a wall of quotes about New Zealand on a small street not far from the harbor. Among them was this from George Bernard Shaw: “If I showed my true feelings, I would cry: it’s the best country I have been in.” Already I knew what he meant. Auckland was a place I’d wanted to see since I was a girl, but what I wasn’t expecting was how immediately at home I felt there. I’d been born in Canada, also part of the Commonwealth; I’d grown up in Fiji, where I’d had Kiwi friends and eaten Kiwi food; and I’d lived decades in Hawai‘i, islands linked to Aotearoa for a thousand years via the Polynesian triangle. Wandering through Auckland I had the strangest sense of being in a place where three disparate strands of my life had been woven together perfectly.

Not that that was what I’d come to Auckland for, though. No, I’d come for the spunk. I’d come to meet some of those self-effacing, candid, can-do Kiwis. And I was not disappointed.

Twelve hours after I arrive, I meet a towering example of just what I’m looking for: Bob Harvey, who last year became Sir Bob Harvey. People get knighted for all sorts of reasons—winning wars, making money--but Sir Bob was knighted for something far more rare and heroic: saving lives. Sixty years ago Bob biked out of Auckland to a vast, wild West Coast beach called Karekare. Huge breakers thundered in off the Tasman Sea. Bob met some young men who offered him a sausage and a beer and the chance to become a lifeguard.

In his first summers he rode out to Karekare on the back of the post truck, thrilled to be a member of its lifesaving surf club. Six decades on, Bob’s still on patrol out at the beach, “a freak of nature” he calls himself. How many’s he saved? “Thousands, maybe? I’m very old,” he says, incredulous. He’s 73 now and doesn’t intend to stop until he’s 80. “Is that reasonable?” he asks me before answering himself, “It’s very unreasonable.” Bob is droll, smart and a diehard storyteller. He regales me with the dramatic tale of the world’s first air-to-sea rescue, which took place in 1935 near Karekare. Bob is in the midst of making a film re-creating the event with his mate Peter Jackson, he of Lord of the Rings fame, though when Bob tells me this there’s not a shred of name dropping – rather it’s as if every person in this nation of 4.5 million is on a chummy first-name basis. And friendly, my God! Kiwis are reputed to be the friendliest people in the world; as a colleague of mine put it, they make Canadians looks like Germans.

Bob’s time as a lifeguard is only a part of his narrative. He was also mayor of West Auckland for eighteen years, from 1992 to 2010. He ran for two reasons. First, to protect the Waitakere range, the dramatic mountains of West Auckland. Karekare is in the Waitakere, and it was there that not only Sir Bob but also his old pal Sir Ed became who they are; Hillary trekked all through the Waitakere, and today the main trail there bears his name. Bob was an oddity when he stood for mayor—“a loopy ad guy and an environmentalist,” he says—but he both won and then won over his constituents: Before he left office an act of Parliament saved the Waitakere from future development. The second reason Bob ran is much more personal: At 50 he discovered that he was adopted. It’s a Philomena-esque story replete with Catholic nuns, a birth in Auckland’s Home of Compassion and the stunning sense, in the middle of Bob’s life, that he had no idea who he was. But in the end, he says, “It made me very strong. It made me courageous.”

Before Bob was mayor he ran a big ad agency and was head of New Zealand’s Labour Party. He introduced Hawaiian outrigger canoes to Auckland and paddled a waka ama in competition; for a time he was driven to make a film on Princess Ka‘iulani, a beloved Hawaiian monarch. Now he’s in charge of the redevelopment of Auckland’s waterfront, a place he calls the “hottest destination in the country.” Sir Bob has a gift for making hyperbole sound like understatement. It’s right there in his name: What could be more aristocratic than “sir,” more plebian than “Bob”? Listening to him I am quite sure that the Auckland waterfront is the hottest destination in the country. I’m equally convinced of love for his city. “It’s a Pacific seaport of real significance,” he says, “more so than any of the Australian ports. Maori coming here by voyaging canoes must have gone, ‘Wow!’”

Auckland is the largest city in Polynesia, but the thing that really gives it its identity is that it’s the largest Polynesian city in the world: While Australia had a whites-only migration policy in the 1950s and ’60s, New Zealand welcomed Islanders from across the Pacific. The estimated number of Pacific Islanders living in Auckland today is 230,000 and one of the biggest events of the year in the city is the Pasifika festival, the largest Pacific Islander cultural festival on earth. Stan Wolfgramm directs the Pasifika fest; he’s the son of a Tongan father and a Cook Islander mother, grew up in Auckland and traveled the world on his good looks, working as a model in Australia and Europe. When he decided to become an actor he studied for two years at the Strasburg Institute in New York and then returned home. But the parts he wanted to play as a Polynesian man didn’t exist, so he wrote them.

We talk on the playing field of the Otara Rugby League, home of the Scorpions. It’s eight on a Saturday morning and hundreds of Polynesian families are on the field--parents with kids they’ve brought to play rugby and netball. Stan is acutely attuned to Pacific Islander realities in Auckland. The neighborhood we’re in now, he tells me, has a higher percentage of Pacific Islanders than any other in the city. The subject of a number of economic initiatives, it’s a lovely, clean, green neighborhood. A friend from Kenya Stan brought here noted it would have been the equivalent of Beverly Hills in his country.

Stan has dedicated his life to telling the stories of just the people we see around us, Pacific stories. Through his company Drum Productions he’s moved from plays to documentaries, television programs, narrative films and events. For six years, he produced and directed Pacific Beat Street, a show on NZ’s TV3 that offered Pacific perspectives; for fifteen years he staged Style Pasifika, an annual fashion show built around Pacific design that grew into a national broadcast held in a twelve-thousand-seat arena. “Success,” says Stan, “is momentum. You‘ve got to keep moving.”

How’s Auckland doing on that score? All in all, very well, is Stan’s opinion—he’s not naïve, but he is optimistic. New Zealand is a small, new country, he says, so it’s easier to make decisions and get things done. “There’s much more accountability here. If you want to meet the prime minister, you can meet the prime minister,” he says, remembering being in a fish-and-chip shop when then-Prime Minister David Lange walked in. Stan also sees New Zealand changing, tempering its colonial past, embracing its Maori and Pacific roots and recognizing the value of its land. “Culture is about heritage and identity,” Stan says, “and that all comes through having this Pacific community.”

Model, actor, writer, director, producer, entrepreneur, cultural ambassador—Stan really is a Renaissance man. When I tell him so, he laughs. “Well, that’s New Zealand,” he says. “If you want to do it, you just have to get up off your ass and do it.”

Neville Findlay teaches me the local term for that Kiwi just-do-it initiative: “The number eight wire mentality,” in reference to the gauge of wire New Zealand farmers employed to string fences across the country: It’s said a Kiwi can do anything with number eight wire. Neville is the husband and collaborator of Elisabeth Findlay, who designs for one of New Zealand’s most acclaimed fashion houses, Zambesi. Elisabeth arrived in New Zealand when she was three years old, courtesy of the Red Cross. She came from Greece in 1951 with her parents, both survivors of Nazi war camps, and her mother taught her the skill she’d learned making German uniforms in the camp: to sew. But if Elisabeth’s provenance was born of a war on the other side of the world, it was nourished by the freedom and isolation of New Zealand. After a stint in an Auckland modeling school as a teenager, where her 5’1” height was a drawback and her perfect bust size an advantage, she got a job at a clothing company. In 1976 she opened her own boutique and in 1979 she started Zambesi. She has designed two collections every year since, building Zambesi into one of the country’s biggest labels. Throughout, she bucked the global trend by foregoing foreign sweatshops and keeping all of the manufacturing in New Zealand. In fact we’re sitting in her factory as we talk, a very mod building filled with people cutting and assembling garments. In a way the factory is a throwback to an earlier time in New Zealand’s history, when high tariffs kept foreign clothing out and virtually everything that Kiwis wore was made locally. As it usually does, necessity gave birth to invention. “We’re very encouraged here to give things a go,” Elisabeth says of the country that has been her home for 63 of her 66 years. “I think anybody can try and do anything in New Zealand if they want to. If it comes from the heart and they are absolutely driven to create something, I think they can—and they probably will.”

Elisabeth’s factory sits just off K Road, short for Karangahape Road, which runs through the center of Auckland. It’s the city’s grittiest, hippest street—its Mission District or SoHo. It has moko (tattoo) parlors and hookah bars and takeaways that sell kebabs and sushi and kale smoothies. It’s got a lot of bars and clubs, too, and at one of them, the Wine Cellar, I hear Ben King play. Ben used to be in one of New Zealand’s most successful bands, Golden Horse; now he’s a music producer who gigs occasionally. He has a sweet quality more akin to an elementary school teacher than a headbanger, and somehow I’m not surprised when he tells me that his parents met in a church choir.

The Wine Cellar is dark, fusty and subterranean—a Petri dish for new music with shades of Liverpool’s legendary Cavern. Several of the rockers who take the stage before Ben are young and trying out new material, a reflection of the fact that music is an ever-larger facet of life in the city: Used to be every kid joined the rugby team at five; now they’re likely to get a guitar then too. Whether they’ll ever make a career of it, that’s another question. New Zealand is, at the end of the day, a small place. Golden Horse had platinum albums and played with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra but barely broke even. “It takes only about a month in New Zealand to tour every venue there is,” notes Ben. After that, unless you want to spend all your time out of the country on the road, you hit the ceiling.

To stay with his muse Ben chose production, and he is not alone in following Stan’s and Elisabeth’s “get-up-off-your-ass” and “give-it-a-go” dicta. “A lot of New Zealanders buy their own equipment and make music and are pretty good at it because they do it a lot,” he says. That, in fact, is the story of Lorde’s producer, Joel Little. He was in one of New Zealand’s other big bands, Goodnight Nurse, which hit the same ceiling. After its demise Joel became a producer. He and Lorde teamed up and cut Royals in an office in suburban Auckland, put it on the Internet and next thing he knew he was collecting a Grammy. “It’s just ridiculous,” says Ben, “like the very unlikely plot of a movie, you know? Lorde’s broken the glass ceiling for people, I suspect. Like, I shouldn’t assume that because I’m in New Zealand and I’m an amateur that I can’t take this as far as I want—because somebody just did.”

The first humans to set foot in the area now known as Auckland were Maori; they settled the area around 1350, calling it Tämaki Makaurau. There were an estimated twenty thousand Maori living in the area when the first Westerners appeared in 1776. Skirmishes ensued between differing iwi (tribes) and between päkeha (foreigners) and Maori. In the resulting upheaval, many Maori left the area; the Auckland of today was largely created by Irish and English settlers. One of the latter named the place, in line with the-sun-never-sets-on-the-Empire ethos of the time, for the Earl of Auckland, then Viceroy of India.

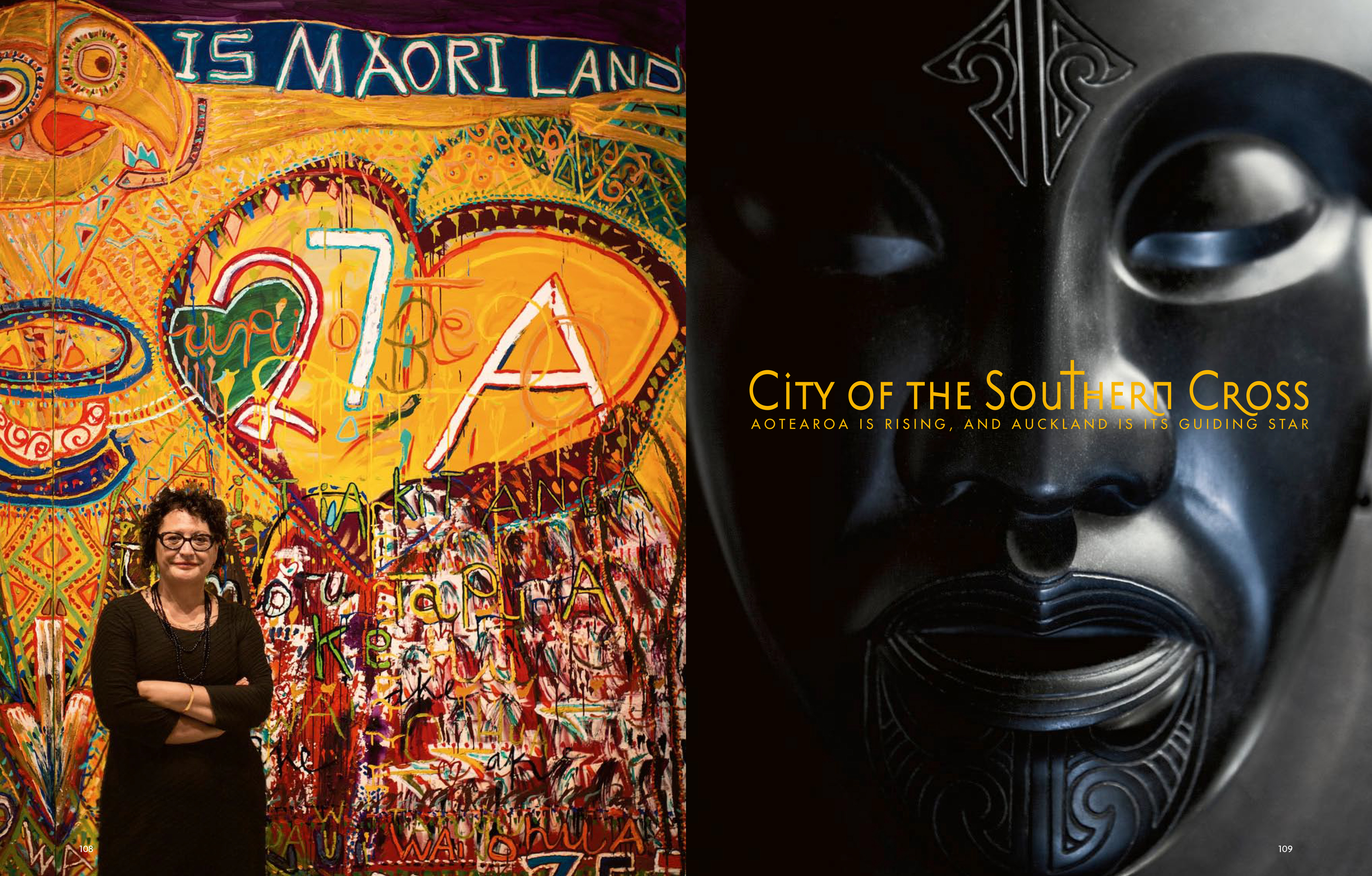

But look for Maori culture in the city today, and you’ll find it. Even before I get to customs in the airport I’m walking through a reproduction of a marae (Maori meeting house). On my first night I see Paniora, a play about a Maori family with an ancestor who was a Spanish vaquero (and a reminder of Aotearoa’s strong links with Hawai‘i, where the vaqueros, or cowboys, were called paniolo). A couple of days later, at the Auckland Art Gallery, I tour a major show by five Maori women painters curated by Ngahiraki Mason, a prominent Maori art historian. The weekend I leave, the country’s Atamira Dance Company is staging a performance inspired by Maori tattoo, Moko.

Walking through the Newmarket neighborhood I come upon a large building—once a carpet factory—that in 2003 became a beacon for Maori not just in Auckland but all across the world: Maori TV, a station that runs programming in te reo, the Maori language. The orange-and-silver building sports a koru, the curled fiddlehead of a fern, a potent Maori symbol of regeneration and the logo of Maori TV. The station went live in 2004 after years of court battles to get funding and in the midst of intense criticism from people who said that it would self-destruct in no time. But when the conch blew at dawn on the station’s first day, with hundreds massed in front of the building including the Maori Queen, a key moment in modern Aotearoa history was at hand.

Haunui Royal was in the building that day, scrambling on production, when the sound of the conch coursed through him. “It overwhelmed me,” he recalls. “I got that sense of ‘Oh my God, it’s reality!’ People around the country went, ‘I can’t believe it, it’s a dream.’” Haunui is today the program manager for Maori TV; he has played a key role in building one of the largest and best indigenous broadcasting channels in the world. In the decade it’s been on air, Maori TV has broken ground with hard-hitting documentaries and news programming, reality shows like Marae DIY, in which marae across Aotearoa are renovated and a live karaoke show called Komoi Tepakipaki (“give me clapping”). It has silenced its critics and become a major and highly respected voice in the country. “Different shows do different jobs,” says Haunui. “Entertainment shows are very big for the Maori audience: We love singing and dancing, we love humor. But there is a hard political side too. Our audiences love political documentaries, current affairs and debate.” Whatever the show, the philosophy that runs through it all, says Haunui, is that the programming is not exploitative. “A lot of television divides us,” he says. “A lot of networks like to focus on the dark stuff, living through other people’s pain. What good is that? I was always of the mind of ‘Where is the light at the end of the tunnel?’”

Haunui has spent time in Tahiti and in Hawai‘i—his wife has paddled both the Moloka‘i Channel and in the Queen Lili‘uokalani races—and he is acutely aware of the links between these three Polynesian nations. “The big bond between all of us is that we are all cultural minorities within a political framework.” Still, he says, he believes the Maori are doing as well as they are today for two reasons: First, he says, echoing Stan, because New Zealand is very small and voices can be made heard; and second, because Maori are not afraid to speak. “We are a martial society,” says Haunui. “We were very good at fighting. We were in your face immediately. I think it was partly the nature of the environment; it’s colder than the other island nations and it’s bigger. There were more tribes and constant friction for land, resources, space and food. Prowess in warfare for men was a big part of the culture. Even the women are eyeballing you. It’s defiance, like, ‘Who are you?’ But once you’re in, you’re all good.”

Before I leave Auckland I drive out to see Sir Bob in Karekare. I find him on the beach resplendent in his Speedos – or, as Kiwis call them, “budgie smugglers.” Karekare was once, eons ago, the interior of a volcano—when a side fell away and the sea rushed in, it became a beach. Its sand is black and powder-fine, its scale more suited to a continent than an island. “Amazingly beautiful,” says Bob of the place, “and as dangerous as it gets.” If you’ve seen The Piano, you’ve seen Karekare; in the 1980s Jane Campion filmed long stretches of the film here. When I arrive, Bob is down by the water chatting to two young Irishmen, recruiting them just as he was recruited sixty years ago. Then he regales me with more tales of dramatic rescues as he takes me on a tour of the beach. Twice the patrol won New Zealand’s Rescue of the Year: first in 1978 when Bob and the rest of the patrol pulled a film crew of twelve Frenchmen and three Englishmen out of the sea. Four had gone in and, when they’d gotten into trouble, everyone else had gone in to help and met the same fate. It was after hours and the lifeguards were all back at the clubhouse when someone came racing in with word. Bob and the others ran to the beach, got two canoes into the water and saved everyone. The group’s grateful leader donated thirty thousand Francs to the club, which bought its first inflatable boat; years later Bob went to England and swam in the Channel with one of the guys he’d saved. The second rescue of the year came in 2000, when the patrol pulled three Koreans off the bottom. They were dead, says Bob—it comes out as “did” in his Kiwi accent—and the guys worked furiously to find a pulse and get them breathing again. The three never regained consciousness before being put on a helicopter to Auckland General, but the next day they all woke up.

We walk to the clubhouse at the edge of the beach. It’s a spartan wood structure with bunk beds and a simple kitchen—a place of tremendous bonhomie over the years. On its walls are pictures dating back to 1961, and Bob’s in every one. The pictures trace his life from an invincible-looking youth through a bodybuilding phase to the beginnings of his life in advertising; in these shots he’s traded his swim togs for a three-piece suit and grown a thick mustache. As his career progresses, you can literally see the life draining out of him: “haggard,” he says, looking at the images now. “Pale and gray. I had to do something.” And he did: The vital man in front of me looks nothing like the forlorn ad man on the wall.

The pictures make me think of that line in the museum—jumping up, falling back but ultimately always climbing. I can see that line running through the lives of so many of the people I’ve met here. I think of another quote I read on the wall that night in Auckland: “Everything that was good from that small remote country had gone into them: sunshine and strength, good sense, patience, the versatility of practical men.” Their city has followed its own upward trajectory. Today it too seems a place full of its own goodness: possibility and exuberance, a love for beauty, open arms and a foundation of beneficence.