Paul Atkins was born in Mobile, Alabama and grew up fascinated by the creatures he saw pulled from the muddy waters of its bay. He learned to fish and then to scuba dive, drawn ever deeper into the sea. He gravitated toward adventure, and even in the stale, segregated confines of Mobile in the 1950s he found it, most reliably in the darkened space of the local movie house, where he thrilled to epics like Lawrence of Arabiaand Mutiny on the Bounty. Paul’s father supplied some too; he ran a banana plantation in British Honduras, patrolling daily with gun in hand, and even once returning home with the skin of a jaguar he’d killed.

At 18 Paul went off to college at Florida State to study marine biology. It was there that the two loves of this youth came together when he shot his first footage: a Super 8mm film of guppies in an aquarium, taken as part of a class project. It was hardly dynamic, but it marked the beginning of a bravura career. Since shooting those guppies Paul has become one of the greatest cinematographers of the natural world, a person whose images of our planet are some of the most grand and glorious ever captured on film, whether it’s plumes of smoke unfurling across a lava field with the grace of dancers, tiny sulfur bubbles scuttling tentatively across a primordial plain, or a huge manta ray gliding like a spaceship through the darkened ocean.

“Paul seems to understand and see things about the natural world that the rest of us cannot,” saysEmmanuel Lubezki, who has won the Academy Award for cinematography an unprecedented three years in a row and a frequent collaborator of Paul’s. “Unless he shoots these events and presents them to us, we’ll never find them. That is what makes him such a special cinematographer. There’s a beautiful, unknowable mystery in the events and subjects he portrays.”Sir David Attenborough is another admirer and collaborator. "Paul is extraordinarily inventive in managing to get sensational close-up shots of animals in action,” says the grand old man of nature documentaries. “He succeeds because of his profound understanding of the animals he films and the risks he runs.”

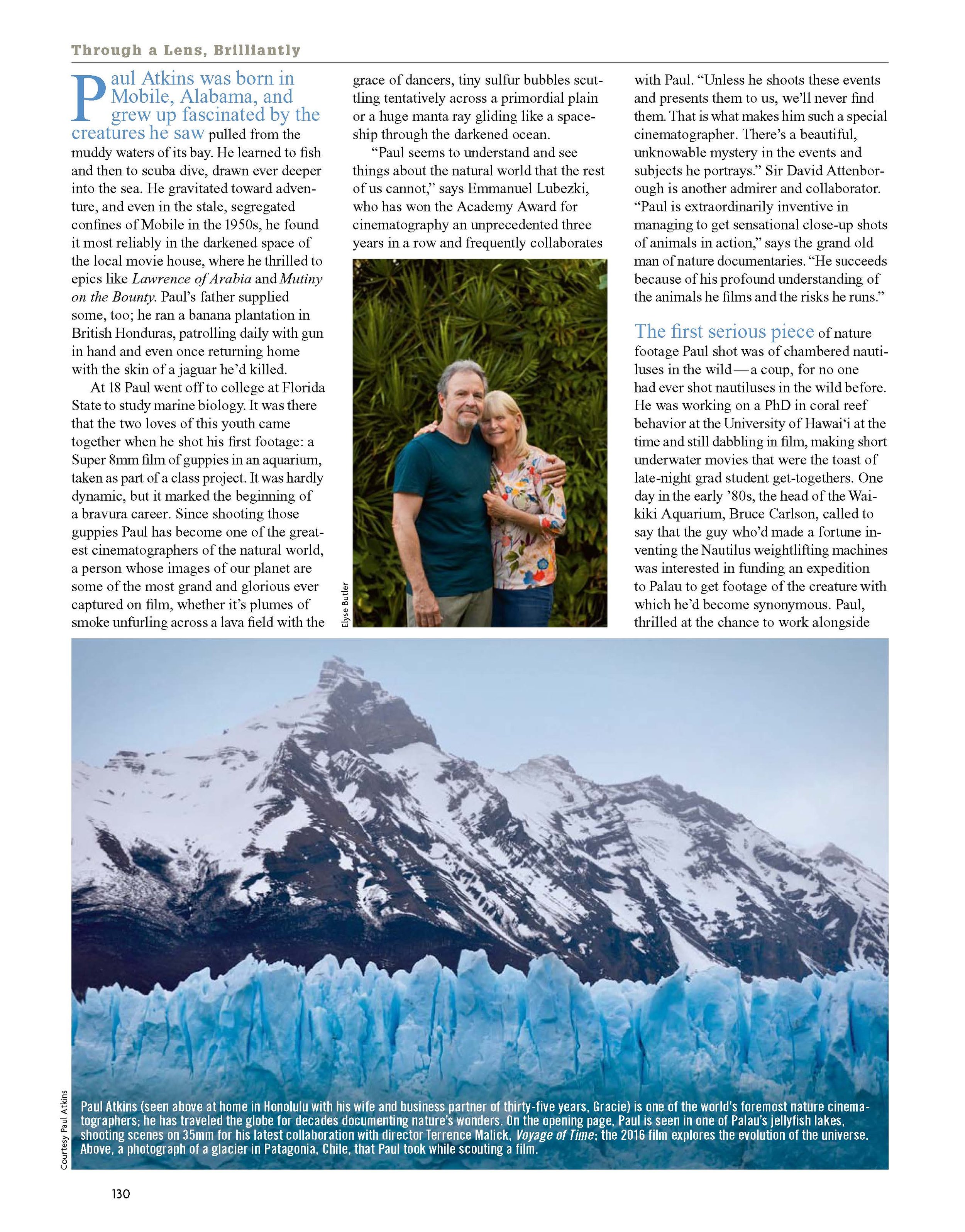

The first serious piece of nature footage Paul shot was of chambered nautiluses in the wild—a coup, for no one had ever shot nautiluses in the wild before. He was working on a PhD in coral reef behavior at the University of Hawai‘i at the time and still dabbling in film, making short underwater movies that were the toast of late-night grad student get-togethers. One day in the early ’80s the head of the Waikiki Aquarium, Bruce Carlson, called to say that the guy who’d made a fortune inventing the Nautilus weightlifting machines was interested in funding an expedition to Palau to get footage of the creature with which he’d become synonymous. Paul, thrilled at the chance to work alongside professionals using serious camera gear, told Carlson he was in. But the story, like the nautilus shell itself, was more convoluted than it initially appeared. It took three years and two trips to Palau to get the footage, but by the end, Paul not only had groundbreaking imagery, he knew how to operate a 16mm camera, he’d chosen filmmaking over academia, and, on trip number two to Palau, he’d married one of his partners in the film, a vivacious blonde he’d met on the beach at Hanauma Bay—Gracie, who to this day Paul calls the yang to his yin. “I’m the dreamer and she’s the business person,” he says of their partnership in the company they’ve built together over the last thirty-five years, Moana Productions. “She gave my dreams reality.”

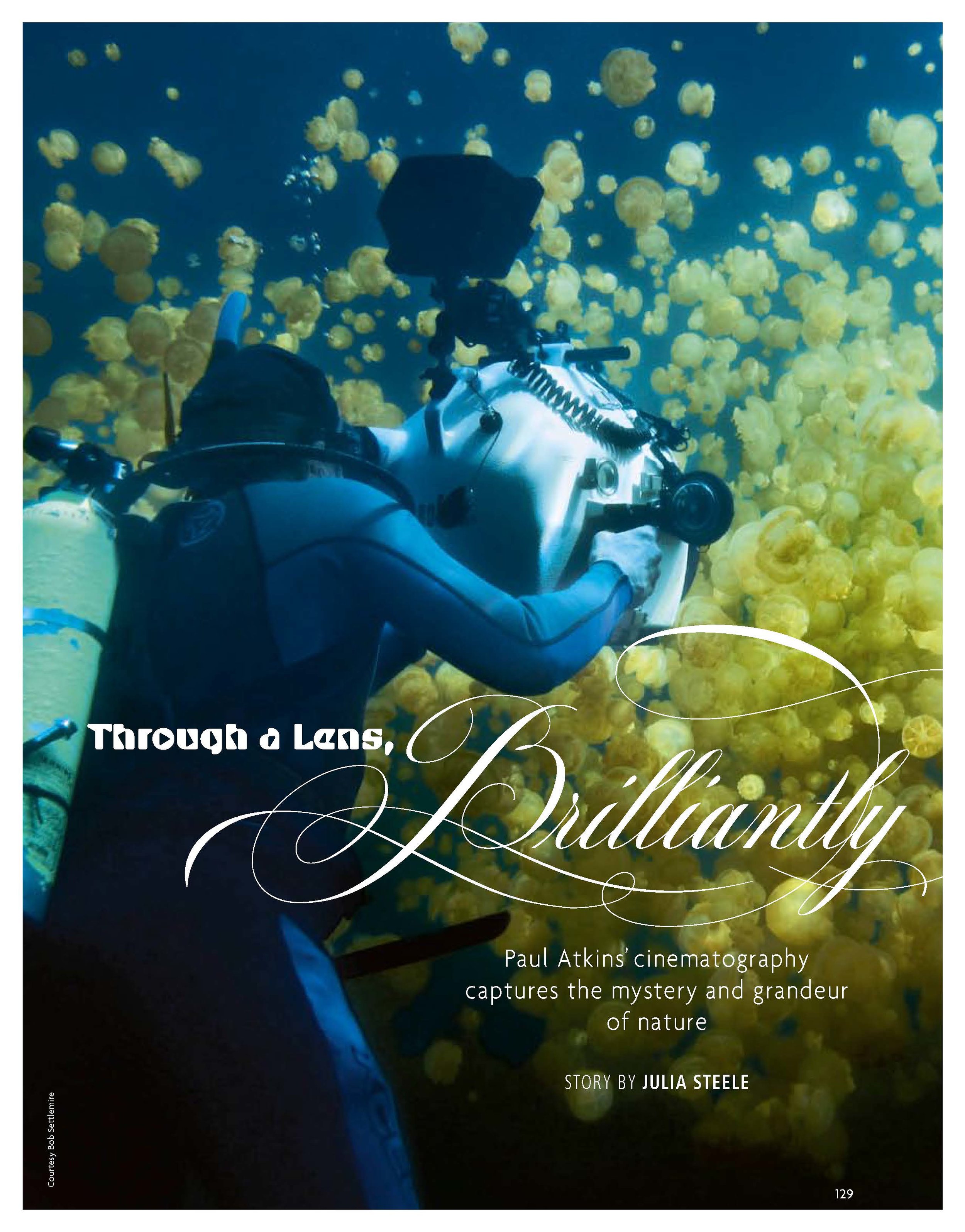

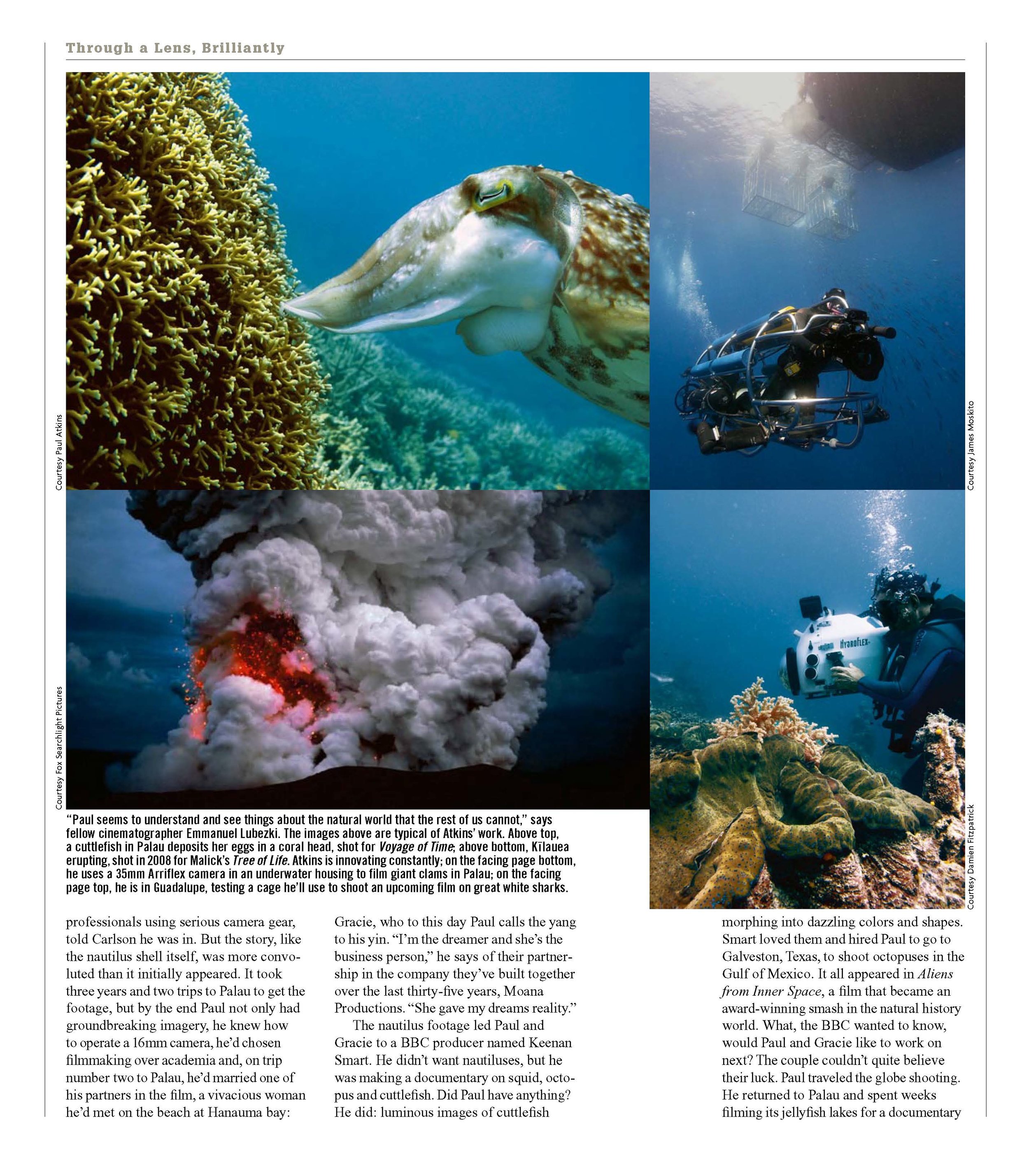

The nautilus footage led Paul and Gracie to a BBC producer named Keenan Smart. Keenan didn’t want nautiluses but he was making a documentary on squid and octopus and cuttlefish. Did Paul have anything? He did: luminous images of cuttlefish morphing into dazzling colors and shapes. Smart loved them and hired Paul to go to Galveston, Texas to shoot octopuses in the Gulf. It all appeared in Aliens from Inner Space, a film that became an award-winning smash in the natural history world. What, the BBC wanted to know, would Paul and Gracie like to work on next? The couple couldn’t quite believe their luck. Paul traveled the globe shooting. He returned to Palau and spent weeks filming its jellyfish lakes to make a documentary called The Lost World of the Medusa. The first time the couple worked with Attenborough it was in Sämoa, shooting a sea full of spawning palolo worms for the series The Trials of Life; next Attenborough and Paul spent weeks in Antarctica for Life in the Freezer. In Hawai‘i, Paul came the closest he ever has to dying in the field while shooting Kïlauea’s eruption for Hawaii:Islands of the Fire Goddess.He was shooting from the ocean, beneath scalding water as molten lava entered the sea, and he narrowly escaped when a newly formed shelf he was filming gave way in a landslide. After Islands of the Fire Goddess, the National Geographic Society came knocking and for them Paul and Gracie created the Emmy-award-winning documentary Strangers in Paradise, which looked at the human impact on Hawai‘i’s ecosystems.

As his career blossomed Paul held to a few truths about himself: He wanted to be a storyteller, not a technician. He wanted to be a generalist, not a specialist. And he wanted to dispel myth with truth. Two of his documentaries in the 1990s did just that, demolishing the narratives first of Jaws, then of Flipper. With Great White SharkPaul took a creature that had been demonized and offered a completely new view of it, renouncing the two mainstays of great white docs: baiting the water and filming from a cage. Instead he traveled to the Farallon Islands and filmed the sharks in their natural environment, using cameras lowered into the sea on poles. The doc offered a more nuanced and accurate view of the fish; it won a BAFTA and an Emmy for cinematography, and to this day Paul meets young biologists who tell him how encouraged they were by it. Next came Dolphins: The Wild Side, which went in the other direction, taking creatures that are largely idolized, Paul laughs, “as superbeings from another planet” and showing that their behaviors can be devious, violent and predatory.

In the midst of it all, the world of television was changing. More channels were appearing and with them sensationalized natural history shows that were built around a host and shot cheaply and quickly—anathema to Paul. “You cannot rush nature,” he says. “The sun will set when it sets. To do quality work, time is the most important factor in the field.” And so he kept diversifying. He built on his skill set by creating commercials through Moana Productions, accepted whatever natural history assignments did appeal and began to think seriously about moving toward the big screen. He didn’t have to wait long.

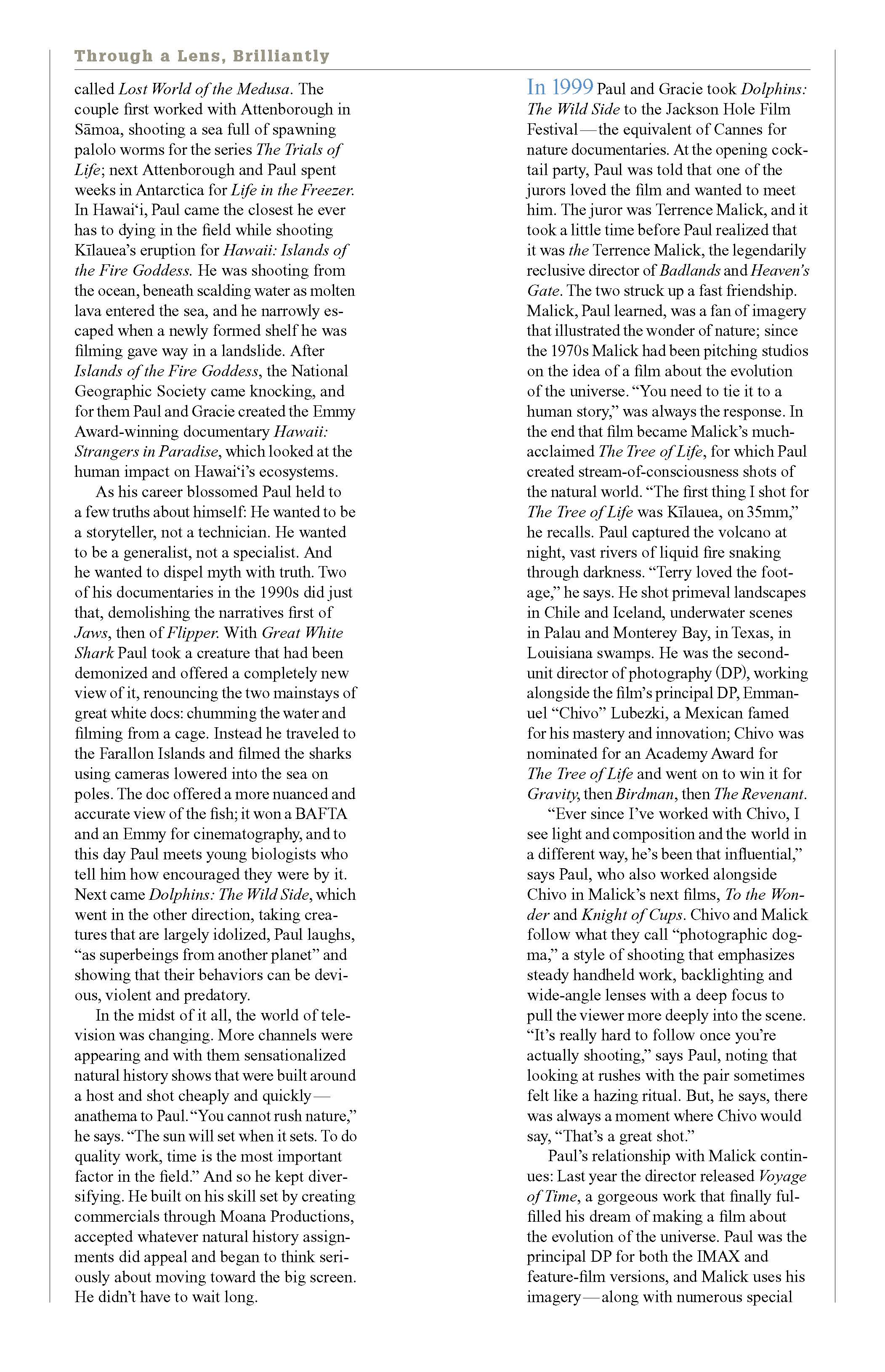

In 1999 Paul and Gracie took Dolphins: The Wild Side to the Jackson Hole Film Festival— the equivalent of Cannes for nature documentaries. At the opening cocktail party, Paul was told that one of the jurors loved the film and wanted to meet him. The juror was Terrence Malick and it took a little time before Paul realized that it was theTerrence Malick, the legendarily reclusive director of Badlands and Heaven’s Gate. The two struck up a fast friendship. Malick, Paul learned, was a fan of imagery that illustrated the wonder of nature; since the 1970s, Malick had been pitching studios on the idea of a film about the evolution of the universe. “You need to tie it to a human story,” was always the response. In the end that film became Malick’s much-acclaimed The Tree of Life, a film for which Paul created stream-of-consciousness shots of the natural world. “The first thing I shot for The Tree of Life was Kïlauea, on 35mm,” he recalls. Paul captured the volcano at night, vast rivers of liquid fire snaking through darkness. “Terry loved the footage,” he says. He shot primeval landscapes in Chile and Iceland for the film, underwater scenes in Palau and Monterey Bay, in Texas, in Louisiana swamps. He was the second-unit director of photography (DP), working alongside the film’s principal DP Emmanuel “Chivo” Lubezki, a Mexican famed for his mastery and innovation; Chivo was nominated for an Academy Award for The Tree of Life and went on to win it for Gravity, then Birdman, then The Revenant.

“Ever since I’ve worked with Chivo I see light and composition and the world in a different way, he’s been that influential,” says Paul, who also worked alongside Chivo in Malick’s next films, To The Wonder and Knight of Cups. Chivo and Malick follow what they call “photographic dogma,” a style of shooting that emphasizes steady handheld work, backlighting and wide-angle lenses with a deep focus to pull the viewer deeper into the scene. “It’s really hard to follow once you’re actually shooting,” says Paul, noting that looking at rushes with the pair sometimes felt like a hazing. But, he says, there was always a moment where Chivo would say, “That’s a great shot.”

Paul’s relationship with Malick continues: Last year the director released Voyage of Time, a gorgeous work that finally fulfilled his dream of making a film about the evolution of the universe. Paul was the principal DP for that film, both the IMAX and feature-film versions, and Malick uses his imagery—along with numerous special effects—to trace a journey that is billions of years old.

Which leads to another truth about Paul’s work—it rarely, if ever, feels small. When he was boy in those Mobile movie theaters, enthralled by films like 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Paul loved the mystery of the unknown and dreamed of going to remote places and finding things no one had seen before. The first time he shot Kïlauea he thought, “This is what I want to do, be this close to something so primordial.” That daring has put Paul on the map. For example: In 2004 he was in a hotel room in XXXXX when a friend at National Geographic called. Had Paul ever heard of an Australian director named Peter Weir? He had. Well, Weir wanted someone to sail around Cape Horn on an eighteenth-century-era square rigger, to chase and film storms for both his upcoming feature Master and Commander: The Far Side of the Worldand a documentary. “I didn’t know who else could do this except you,” Paul’s friend said. “Have him call me,” Paul replied.

He spent forty-two days on a replica of Captain Cook’s 109-foot ship, Endeavour, sailing in Antarctic waters and enduring seventy-five-knot winds and fifty-foot breaking seas. The ship was alone, with no escort vessel, but that didn’t stop Paul and the ship’s captain, Chris Blake, from sailing for the worst weather they could find. When it was over Paul had filmed four “frightening and extraordinary” storms to provide Weir with just what he was looking for: the real thing, not CGI.

Given where he’s been and all that he’s seen, Paul’s love for our planet is deep and abiding. “A big part of my professional life has been about enlightening people about the natural world,” he says. “I feel that now it’s a war against ignorance.” In recent years he’s traveled to the Philippines and Australia to document coral bleaching—and witnessed destruction on a scale shocking even to him—for National Geographic’s series on climate change, Years of Living Dangerously. The ocean wilderness, says Paul, is his great stabilizer, the force that puts things in perspective. In 2006 he was DP for a documentary by Jean-Michel Cousteau on the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. He spent weeks traveling with Cousteau and crew, shooting albatross, monk seals, sea turtles, tabletop corals, jacks and sharks—and the plastic and debris that have become ubiquitous in the area. Each night at dinner the crew would gather over French wine and stories. Many of them had been aboard the original Calypso—a thrill for Paul, who has a boy had been riveted by Jacques Cousteau’s TV shows. The NWHI documentary they created was shown in the White House, and soon after then-President George W. Bush signed legislation to designate the area the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument.

For all of his passion to draw attention to the threats to the natural world, at 67 Paul remains the generalist he always aimed to be. In recent years he was the second-unit DP on Point Break and The Revenant, worked on Jumanji and shot part of an iMac commercial. He regularly films for Hawaii Five-0 and just finished an IMAX sequence on dolphins for a Disney feature. He has plans to direct a feature himself that would return him to the world of great white sharks.

He talks of the films of the ’60s and ’70s, “an amazing time of creative explosion and experimentation in cinema unlike any period we've seen since,” he says. He mentions his inspirations from the time: John Alonzo, who shot one of his all-time favorites, Chinatown; and Conrad Hall, who did Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid; Gordon Willis with The Godfather; Vittorio Storaro and Apocalypse Now. The cinematic richness continues: Paul mentions 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Thin Red Line as films he could watch again and again. He remembers a moment from early in his career when he was trying to get hired on a series called Portrait of America. The work was cultural, focused on human beings, and a friend of his was trying to convince the producers that Paul was their man, even if everything on his demo reel was underwater. “The guy shoots fish,” the producers said. “Yeah, but if he can do that with fish, imagine what he can do with people!” the friend shot back. And Paul got the job.