The back roads of our Islands are full of surprises: Travel down a slim, rutted lane between coconut palms and cane stalks or papaya and banana trees, and you are not, frankly, expecting to find a primate sanctuary or a Beatles museum or a garden planted in the shape of the Milky Way or any of the other winsome oddities that are out there in Hawai‘i’s boonies. Now comes Atelier Maui, one of our newest rural curiosities, which gives all of the others a run for their money. It sits on a bucolic patch of land in Ha‘ikü, a collection of buildings surrounded by tropical greenery—not a place you expect to find artistic training drawn from the Russian Imperial Academy. Open the door to what looks like the barn, though, and prepare for a perestroika of perception:

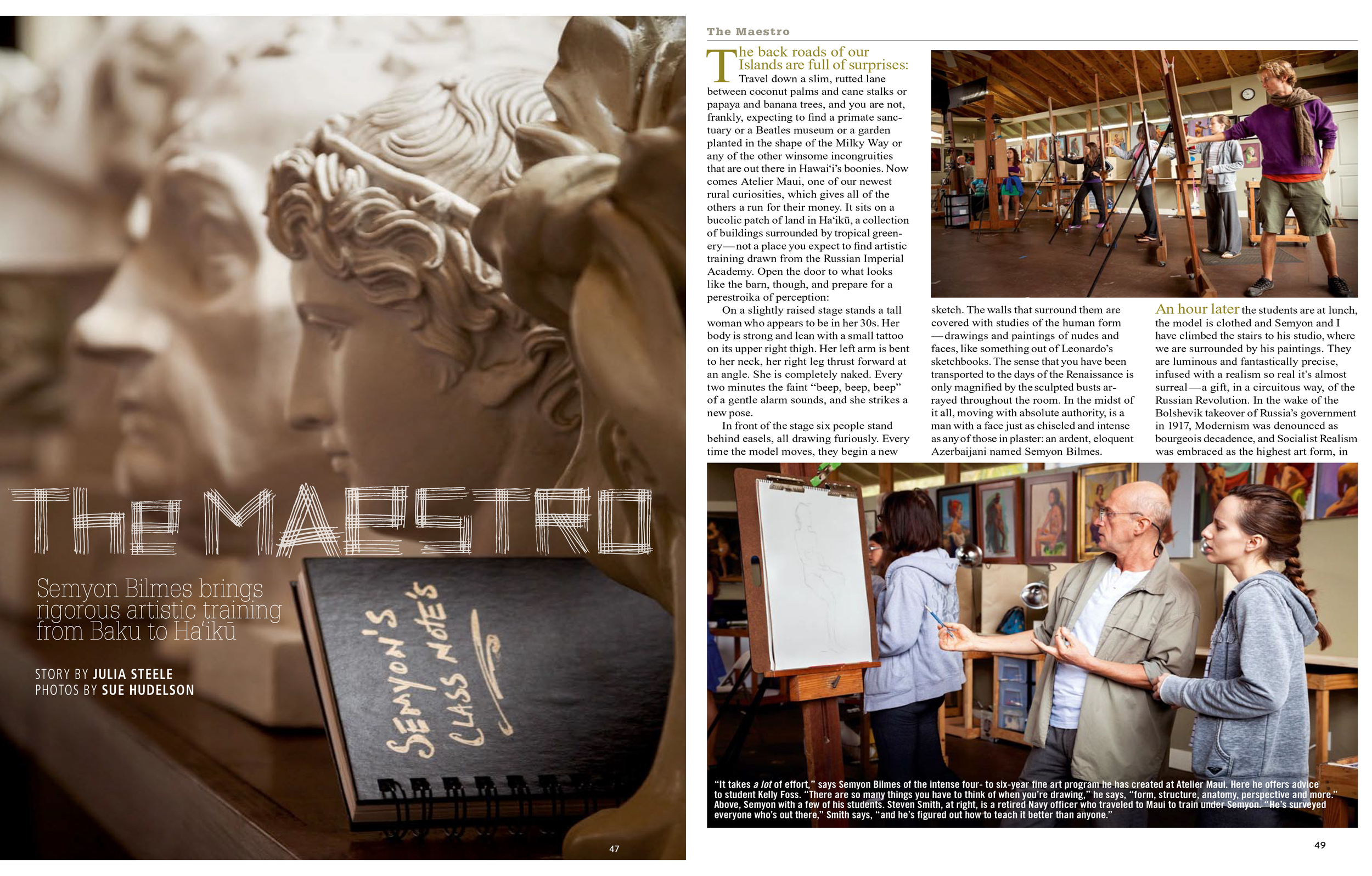

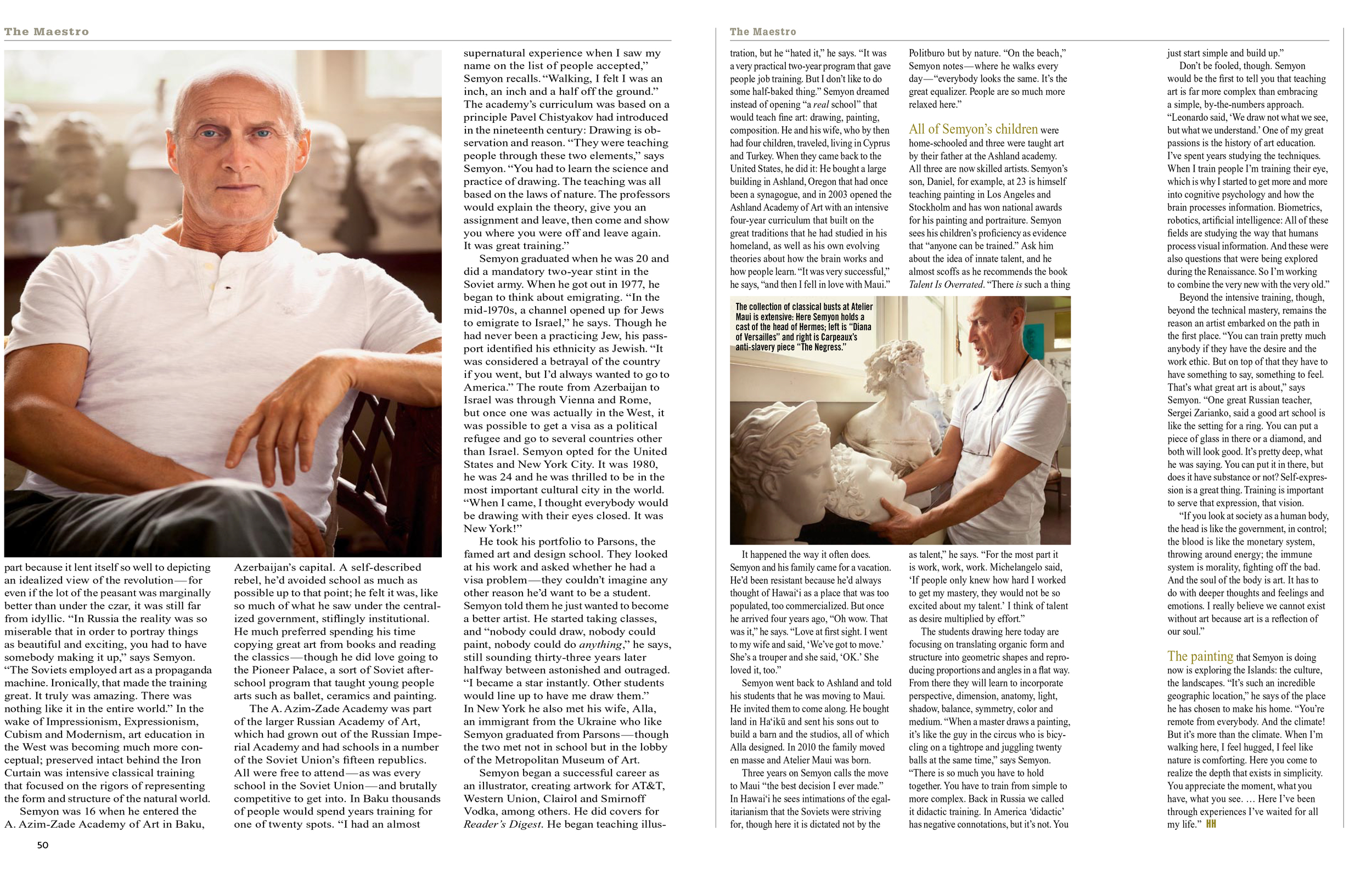

On a slightly raised stage stands a tall woman who appears to be in her 30s. Her body is strong and lean with a small tattoo on its upper right thigh. Her left arm is bent to her neck, her right leg thrust forward at an angle. She is completely naked. Every two minutes the faint “beep, beep, beep” of a gentle alarm sounds, and she strikes a new pose. In front of the stage six people stand behind easels, all drawing furiously. Every time the model moves, they begin a new sketch. The walls that surround them are covered with studies of the human form—drawings and paintings of nudes and faces, like something out of Leonardo’s sketchbooks. The sense that you have been transported to the days of the Renaissance is only magnified by the sculpted busts arrayed throughout the room. In the midst of it all, moving with absolute authority, is a man with a face just as chiseled and intense as any of those in plaster: an ardent, eloquent Azerbaijani named Semyon Bilmes.

An hour later the students are at lunch, the model is clothed and Semyon and I have climbed the stairs to his studio, where we are surrounded by his paintings. They are luminous and fantastically precise, infused with a realism so real it’s almost surreal—a gift, in a circuitous way, of the Russian Revolution. In the wake of the Bolshevik takeover of Russia’s government in 1917, Modernism was denounced as bourgeois decadence, and Socialist Realism was embraced as the highest art form, in part because it lent itself so well to depicting an idealized view of the revolution—for even if the lot of the peasant was marginally better than under the czar, it was still far from idyllic. “In Russia the reality was so miserable that in order to portray things as beautiful and exciting, you had to have somebody making it up,” says Semyon. “The Soviets employed art as a propaganda machine. Ironically, that made the training great. It truly was amazing. There was nothing like it in the entire world.” In the wake of Impressionism, Expressionism, Cubism and Modernism, art education in the West was becoming much more conceptual; preserved intact behind the Iron Curtain was intensive classical training that focused on the rigors of representing the form and structure of the natural world.

Semyon was 16 when he entered the A. Azim-Zade Academy of Art in Baku, Azerbaijan’s capital. A self-described rebel, he’d avoided school as much as possible up to that point; he felt it was, like so much of what he saw under the centralized government, stiflingly institutional. He much preferred spending his time copying great art from books and reading the classics—though he did love going to the Pioneer Palace, a sort of Soviet after-school program that taught young people arts such as ballet, ceramics, drawing and painting.

The A. Azim-Zade Academy was part of the larger Russian Academy of Art, which had grown out of the Russian Imperial Academy and had schools in a number of the Soviet Union’s fifteen republics. All were free to attend—as was every school in the Soviet Union—and brutally competitive to get into. In Baku thousands of people would spend years training for one of twenty spots. “I had an almost supernatural experience when I saw my name on the list of people accepted,” Semyon recalls. “Walking, I felt I was an inch, an inch and a half off the ground.” The academy’s curriculum was based on a principle Pavel Chistyakov had introduced in the nineteenth century: Drawing is observation and reason. “They were teaching people through these two elements,” says Semyon. “You had to learn the science and practice of drawing. The teaching was all based on the laws of nature. The professors would explain the theory, give you an assignment and leave, then come and show you where you were off and leave again. It was great training.”

Semyon graduated when he was 20 and did a mandatory two-year stint in the Soviet army. When he got out in 1977, he began to think about emigrating. “In the mid-1970s, a channel opened up for Jews to emigrate to Israel,” he says. Though he had never been a practicing Jew, his passport identified his ethnicity as Jewish. “It was considered a betrayal of the country if you went, but I’d always wanted to go to America.” The route from Azerbaijan to Israel was through Vienna and Rome, but once you were actually in the West, it was possible to get a visa as a political refugee and go to several countries other than Israel. Semyon opted for the United States and New York City. It was 1980, he was 24 and he was thrilled to be in the most important cultural city in the world. “When I came, I thought everybody would be drawing with their eyes closed. It was New York!”

He took his portfolio to Parsons, the famed art and design school. They looked at his work and asked whether he had a visa problem—they couldn’t imagine any other reason he’d want to be a student. Semyon told them he just wanted to become a better artist. He started taking classes, and “nobody could draw, nobody could paint, nobody could do anything,” he says, still sounding thirty-three years later halfway between astonished and outraged. “I became a star instantly. Other students would line up to have me draw them.” In New York he also met his wife, Alla, an immigrant from the Ukraine who like Semyon graduated from Parsons—though the two met not in school but in the lobby of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Semyon began a successful career as an illustrator, creating artwork for AT&T, Western Union, Clairol and Smirnoff Vodka, among others. He did covers for Reader’s Digest. He began teaching illustration, but he “hated it,” he says. “It was a very practical two-year program that gave people job training. But I don’t like to do some half-baked thing.” Semyon dreamed instead of opening “a real school” that would teach fine art: drawing, painting, composition. He and his wife, who by then had four children, traveled, living in Cyprus and Turkey. When they came back to the United States, he did it: He bought a large building in Ashland, Oregon that had once been a synagogue, and in 2003 opened the Ashland Academy of Art with an intensive four-year curriculum that built on the great traditions that he had studied in his homeland, as well as his own evolving theories about how the brain works and how people learn. “It was very successful,” he says, “and then I fell in love with Maui.”

It happened the way it often does. Semyon and his family came for a vacation. He’d been resistant because he’d always thought of Hawai‘i as a place that was too populated, too commercialized. But once he arrived four years ago, “Oh wow. That was it,” he says. “Love at first sight. I went to my wife and said, ‘We’ve got to move.’ She’s a trouper and she said, ‘OK.’ She loved it, too.”

Semyon went back to Ashland and told his students that he was moving to Maui. He invited them to come along. He bought land in Ha‘ikü and sent his sons out to build a barn and the studios, all of which Alla designed. In 2010 the family moved en masse and Atelier Maui was born.

Three years on Semyon calls the move to Maui “the best decision I ever made.” In Hawai‘i he sees intimations of the egalitarianism that the Soviets were striving for, though here it is dictated not by the Politburo, but by nature. “On the beach,” Semyon notes—where he walks every day—“everybody looks the same. It’s the great equalizer. People are so much more relaxed here.”

All of Semyon’s children were home-schooled and three were taught art by their father at the Ashland academy. All three are now skilled artists. Semyon’s son, Daniel, for example, at 23 is himself teaching painting in Los Angeles and Stockholm and has won national awards for his painting and portraiture. Semyon sees his children’s proficiency as evidence that “anyone can be trained.” Ask him about the idea of innate talent, and he almost scoffs as he recommends the book Talent Is Overrated. “There is such a thing as talent,” he says. “For the most part it is work, work, work. Michelangelo said, ‘If people only knew how hard I worked to get my mastery, they would not be so excited about my talent.’ I think of talent as desire multiplied by effort.”

The students drawing here today are focusing on translating organic form and structure into geometric shapes and reproducing proportions and angles in a flat way. From there they will learn to incorporate perspective, dimension, anatomy, light, shadow, balance, symmetry, color and medium. “When a master draws a painting, it’s like the guy in the circus who is bicycling on a tightrope and juggling twenty balls at the same time,” says Semyon. “There is so much you have to hold together. You have to train from simple to more complex. Back in Russia we called it didactic training. In America ‘didactic’ has negative connotations, but it’s not. You just start simple and build up.”

Don’t be fooled, though. Semyon would be the first to tell you that teaching art is far more complex than embracing a simple, by-the-numbers approach. “Leonardo said, ‘We draw not what we see, but what we understand.’ One of my great passions is the history of art education. I’ve spent years studying the techniques. When I train people I’m training their eye, which is why I started to get more and more into cognitive psychology and how the brain processes information. Biometrics, robotics, artificial intelligence: All of these fields are studying the way that humans process visual information. And these were also questions that were being explored during the Renaissance. So I’m working to combine the very new with the very old.”

Beyond the intensive training, though, beyond the technical mastery, remains the reason an artist embarked on the path in the first place. “You can train pretty much anybody if they have the desire and the work ethic. But on top of that they have to have something to say, something to feel. That’s what great art is about,” says Semyon. “One great Russian teacher, Sergei Zarianko, said a good art school is like the setting for a ring. You can put a piece of glass in there or a diamond, and both will look good. It’s pretty deep, what he was saying. You can put it in there, but does it have substance or not? Self-expression is a great thing. Training is important to serve that expression, that vision.

“If you look at society as a human body, the head is like the government, in control; the blood is like the monetary system, throwing around energy; the immune system is morality, fighting off the bad. And the soul of the body is art. It has to do with deeper thoughts and feelings and emotions. I really believe we cannot exist without art because art is a reflection of our soul.”

The painting that Semyon is doing now is exploring the Islands: the culture, the landscapes. “It’s such an incredible geographic location,” he says of the place he has chosen to make his home. “You’re remote from everybody. And the climate! But it’s more than the climate. When I’m walking here, I feel hugged, I feel like nature is comforting. Here you come to realize the depth that exists in simplicity. You appreciate the moment, what you have, what you see. … Here I’ve been through experiences I’ve waited for all my life.”